|

|

|

UN BRINDISI, CINCIN, ALLA SALUTE…

Brindare, (secondo vari vocabolari: Treccani, Garzanti Linguistica, e La

Repubblica) significa:

1. gesto che consiste nell’alzare e toccare insieme i bicchieri prima di bere. È un

invito a bere alla salute o in onore di qualcuno o come buon auspicio [seguito

dalle preposizioni a, per]. Per esempio: fare, proporre un brindisi al festeggiato,

per la vittoria, in onore di un ospite, ecc.

2. breve componimento poetico improvvisato, che si recita al momento del

brindisi.

3. in musica: Aria cantata nelle scene conviviali. (Per esempio: “Libiamo”

dall’opera La Traviata di Giuseppe Verdi.)

Quando brindiamo diciamo alla salute, cent’anni, o cincin.

La parola “brindisi” deriva dal tedesco: (ich) bring(e) dir’s: lo porto, lo offro a te

(il bicchiere, il saluto). Mentre, l’espressione cincin deriva dal cinese mandarino

di Pechino: ch’ing-ch’ing significa prego-prego.

E ora il mio brindisi:

MAKE A TOAST, DRINK TO SOMEONE’S HEALTH…

The Italian word “brindare” (according to various dictionaries: Treccani, Garzanti

Linguistica, and La Repubblica) refers to:

1. A gesture consisting of raising and touching glasses prior to drinking. It is an

invitation to drink to someone’s health, or in honor of someone, or for good

wishes [in Italian the word is followed by the prepositions “a/to”, “per/for”]. For

example: propose a toast to the birthday girl/boy, victory, the guest of honor, etc.

2. Brief poetic and spontaneous composition that is recited at the time of the

toast.

3. In music: an aria sung in convivial scenes. (For example: “Libiamo” from the

opera La Traviata by Giuseppe Verdi.)

When we toast we say: to health, 100 years, or cincin.

The word “brindisi” derives from the German: (ich) bring(e) dir’s I bring, I offer

to you (the glass, the wish). While the expression cincin comes from the

mandarin Chinese spoken in Beijing: ch’ing-ch’ing means please-please.

And now my toast: (a wish for peace and serenity, not only for New Year’s Day,

but for the entire coming year.)

HAPPY NEW YEAR TO ALL!

Saturday, December 28, 2024

|

|

HO TROVATO QUESTO BELLISSIMO AUGURIO NATALIZIO E

VORREI CONDIVIDERLO CON VOI:

|

VI AUGURO UN BUON NATALE DA PARTE MIA.

I found this lovely christmas wish and I would like to share it with you:

To who loves to sleep but wakes up always in a good mood; to who

still greets other with a kiss; to who works much but enjoys even more;

to who is in a hurry but doesn’t tap the car horn at traffic lights; to who

arrives late but doesn’t look for excuses; to who turns off the television

in order to chat; to who is twice as happy when dividing in half; to who

rises early to help a friend; to who has the enthusiasm of a child but

the thoughts of and adult; to who sees black only when it is dark; to

who doesn’t wait for Christmas to be better.

I wish you a Merry Christmas!

Saturday, December 14, 2024

|

| |

|

|

|

BOH!

Secondo l’Accademia della Crusca: l'etimologia delle interiezioni (come scrive

Giovanni Nencioni) non è sempre accertata, anche se ci sono casi in cui essa

risulta più chiara.

L’interiezione Boh esprime dubbio, indifferenza, reticenza a pronunciarsi su

qualcosa; è caratteristica, ma non esclusiva, dell'uso regionale romano, come

si ricava da diversi esempi pasoliniani di Ragazzi di vita. Tuttavia,

sembrerebbe essere semplicemente un'espressione onomatopeica (così T. De

Mauro nel Grande Dizionario italiano dell'Uso, UTET, Torino, 2000), cioè una

trascrizione di un probabile suono che si produce quando si esprime incertezza.

Secondo l’Enciclopedia Treccani: Boh (bo’) Esprime incertezza o incredulità (boh!

non lo so proprio; boh! se lo dice lui, può anche essere vero), oppure disprezzo,

riprovazione, con valore affine a poh.

According to the Accademia della Crusca: the etymology of interjections (as

Giovanni Nencioni writes) is not always easy to ascertain, even if there are cases

in which the origin is clearer.

The interjection Boh expresses doubt, indifference, reticence to comment on

something; it is characteristic, but not exclusive, of Roman regional use, as can

be seen from several examples in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Ragazzi di vita (1955).

However, it seems to be simply an onomatopoeic expression (according to T. De

Mauro in the Grande Dizionario italiano dell'Uso, UTET, Turin, 2000), that is, a

transcription of a probable sound that is produced when uncertainty is expressed.

According to the Enciclopedia Treccani: Boh (bo') Expresses uncertainty or

disbelief (boh! I really don't know; boh! if he says so, it could also be true), or

contempt, disapproval, with a value similar to poh.

Saturday, November 30, 2024

|

|

WHAT WAS EATEN AT THE FIRST THANKSGIVING?

The History Channel reports that no record exists of the first Thanksgiving

menu. Although turkey has become the official mascot of Thanksgiving

Day, many historians believe it was likely not a part of the original feast.

Here's a list of foods that might've appeared on the table instead:

· Deer, likely roasted over a smoldering fire or made into a stew.

· Local vegetables such as onions, beans, lettuce, spinach, cabbage, carrots and

peas. peas.

· Indigenous fruits such as blueberries, plums, grapes, gooseberries, raspberries

and cranberries. and cranberries.

· Corn, likely pounded into a thick corn mush or porridge.

· Various types of seafood like mussels, lobster, bass, clams and oysters.

· Pumpkin custard.

· Root vegetables like turnips and groundnuts.

[Reported by Haadiza Ogwude and Olivia Munson -- Cincinnati Enquirer]

COSA È STATO MANGIATO AL PRIMO RINGRAZIAMENTO?

History Channel riporta che non esiste alcuna registrazione del primo menu del

Ringraziamento. Sebbene il tacchino sia diventato la mascotte ufficiale del

Giorno del Ringraziamento, molti storici ritengono che probabilmente non facesse

parte della festa originale. Ecco un elenco di alimenti che potrebbero invece

essere comparsi sulla tavola:

• Cervo, probabilmente arrostito su un fuoco ardente o trasformato in uno stufato.

• Verdure locali come cipolle, fagioli, lattuga, spinaci, cavoli, carote e piselli.

• Frutti autoctoni come mirtilli, prugne, uva, uva spina, lamponi e mirtilli rossi.

• Mais, probabilmente pestato fino a ottenere una densa poltiglia o porridge.

• Vari tipi di frutti di mare come cozze, aragoste, spigole, vongole e ostriche.

• Crema pasticcera alla zucca.

• Ortaggi a radice come rape e arachidi.

[Riportato da Haadiza Ogwude e Olivia Munson -- Cincinnati Enquirer]

Saturday, November 15, 2024

|

|

| |

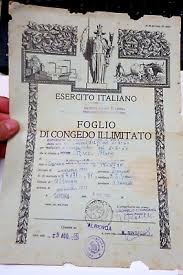

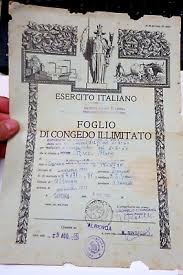

Qual è la differenza tra la foglia e il foglio?

La volta scorsa abbiamo esaminato LA FOGLIA.

Questa volta consideriamo IL FOGLIO, con i suoi significati e usi interessanti.

IL FOGLIO:

1. Pezzo di carta; Marisa ha preso un foglio dal suo quaderno e ha scritto una poesia.

2. Strato sottile; lamina; Il pannello è composto da fogli di compensato.

3. Certificato, documento ufficiale; Giuseppe guida con il foglio rosa per adesso.

Il foglio rosa è “l'autorizzazione ad esercitarsi alla guida, colloquialmente nota come

"foglio rosa" per via della colorazione del fronte. Specificamente è un'autorizzazione

amministrativa della Repubblica Italiana che consente ad un candidato richiedente

la patente di guida italiana di fare pratica in vista dell'esame pratico.”

Abbiamo anche:

4. Foglio di calcolo: un foglio di lavoro “Excel”

5. Foglio di congedo: dal servizio militare

6. Foglio di via: fuoriuscita di un immigrante dal paese

7. Foglio firme: registro dei dipendenti

8. Foglio illustrativo: che elenca le istruzioni

What is the difference between la foglia and il foglio?

Last time we examined “LA FOGLIA”. This time we will take into consideration

IL FOGLIO, with all its meanings and interesting usages.

IL FOGLIO:

1. A piece (sheet) of paper: Marisa took a piece (sheet) of paper from

her notebook and wrote a poem.

2. A thin layer: The panel is composed of thin layers of plywood.

3. Certificate, official document: For now, Joseph is driving with a pink sheet.

The pink sheet is “the authorization to ‘practice’ driving, colloquially known as

the "pink sheet" due to the coloring of the front. Specifically, it is an

administrative authorization issued by the Republic of Italy which allows a

candidate applying for an Italian driver’s license to practice prior to taking the

written and driving exam.” [It is equivalent to a learner’s permit in the US and

does not mean having title to a vehicle.]

We also have:

4. “Excel” worksheet

5. Military discharge papers

6. Deportation orders

7. Signature pages of dependent workers

8. Instruction sheet

Saturday, November 1, 2024

|

|

| |

Qual è la differenza tra la foglia e il foglio?

Questa volta consideriamo LA FOGLIA, con i suoi significati e origini interessanti.

La prossima volta, esamineremo IL FOGLIO.

La foglia:

1. Parte della pianta; Dopo il temporale non è rimasta nemmeno una

foglia sull’albero. foglia sull’albero.

2. Metallo; lamina; La cupola della cattedrale è stata ricoperta di foglie 2. Metallo; lamina; La cupola della cattedrale è stata ricoperta di foglie

d’oro. d’oro.

3. Dell’insalata; Gli ospiti hanno mangiato tutto, non è rimasta neanche

una foglia di lattuga nell’insalatiera. una foglia di lattuga nell’insalatiera.

Non dimentichiamo il detto “mangiare la foglia” che significa “sentire puzza di

bruciato”.

Secondo questo articolo che ho trovato a

www.finedininglovers.it/articolo/mangiare-la-foglia: <<Chi ha "mangiato la

foglia" ha capito il senso nascosto delle cose, ha letto tra le righe. Più spesso

coloro che "mangiano la foglia" hanno capito cosa sta succedendo alle proprie

spalle. Ma da dove arriva questo modo di dire? Le origini di mangiare la foglia

sono davvero antiche. Risalgono infatti al VI secolo d.C. [sic—dovrebbe essere il

VIII secolo a.C.] ovvero a quando Omero scrisse l'Odissea, il grande poema epico

dedicato alle gesta di Ulisse.

In particolare nell'episodio in cui l'eroe finisce prigioniero sull'isola della maga

Circe e scopre il suo trucco per trasformare gli uomini in porci. L'unico modo per

restare immune dalla magia è di mangiare una foglia di moli, offertagli dal dio

Ermes. Il moli era una pianta immaginaria, che alcuni ritengono fosse ispirata all'

aglio.

Così nel momento in cui Ulisse mangia la foglia di moli, è come se prendesse

coscienza della magia della maga diventandone immune.

Secondo alcuni, il modo di dire mangiare la foglia deriva dall'abitudine dei bachi

da seta di assaggiare le foglie per accertarsi che siano commestibili. Tra le

possibili spiegazioni e origini c'è anche la tendenza di alcuni pastori di

assaggiare l'erba dei pascoli per scegliere la migliore per il proprio gregge.

Non possiamo non citare la spiegazione più simbolica: quando gli animali da

pascolo smettono con il latte e cominciano a nutristi anche di erba e foglie

diventano di fatto adulti e più consapevoli.>>

What is the difference between la foglia and il foglio?

This time we will look at LA FOGLIA, with its meanings and interesting usages.

Next time we will examine IL FOGLIO.

LA FOGLIA (leaf):

1. Part of a plant: After the storm, not even one leaf was left on the trees.

2, Metal, laminate: The cupola of the cathedral was covered in gold leaf.

3. Lettuce leaf: The guests ate everything, there wasn’t even a leaf of

lettuce left in the salad bowl. lettuce left in the salad bowl.

Let’s not forget the saying “eat the leaf” which means to “smell a rat”.

According to this article I found on

www.finedininglovers.it/articolo/mangiare-la-foglia: <<Those who have "eaten

the leaf" have understood the hidden meaning of things, they have read between

the lines. More often those who "take the bait" have understood what is

happening behind their backs. But where does this saying come from? The

origins of eating the leaf are truly ancient. In fact, they date back to the 6th

century AD [sic—should be 8th century BCE], that is, when Homer wrote the

Odyssey, the great epic poem dedicated to the exploits of Ulysses.

Particularly in the episode in which the hero ends up a prisoner on the island of

the sorceress Circe and discovers her trick to transform men into pigs. The only

way to remain immune to her magic is to eat a “moli” leaf, offered to him by the

god Hermes. Moli was a fictional plant, which some believe was inspired by

garlic. So, when Ulysses eats the moli leaf, it is as if he becomes aware of the

sorceress' magic and thus immune to it.

According to some, the expression "eat the leaf" comes from the silkworms'

habit of tasting leaves to make sure they are edible. Among the possible

explanations and origins there is also the tendency of some shepherds to taste

the grass of the pastures to choose the best for their flocks.

We cannot fail to mention the most symbolic explanation: when grazing animals

stop drinking milk and start feeding on grass and leaves, they actually become

adults and more aware.

Saturday, October 19, 2024

|

|

ALCUNE GIORNATE FESTIVE:

Il 4 ottobre è considerato solennità civile e giornata della pace,

della fraternità e del dialogo tra appartenenti a culture e

religioni diverse, in onore dei Santi Patroni speciali d'Italia San

Francesco d'Assisi e Santa Caterina da Siena, ai sensi

dell'articolo 3 della legge 27 maggio 1949, n. 260.

La legge del 27 maggio 1949, numero 260 (Pubblicata nella

Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 124 del 31 maggio 1949) tratta delle Dispos

izioni in materia di ricorrenze festive, in oltre alla parte

dell’Articolo 3 sopracitato, [siamo ai primi di ottobre dopo tutto]

dichiara: Art. 1. Il giorno 2 giugno, data di fondazione della

Repubblica, è dichiarato festa nazionale. Articolo 2. Sono

considerati giorni festivi, agli effetti della osservanza del

completo orario festivo e del divieto di compiere determinati atti

giuridici, oltre al giorno della festa nazionale (1), i giorni

seguenti: tutte le domeniche; il primo giorno dell'anno; il giorno

dell'Epifania (2); il giorno della festa di San Giuseppe (3); il 25

aprile, anniversario della liberazione; il giorno di lunedì dopo

Pasqua; il giorno dell'Ascensione (4); il giorno del Corpus Domini

(5); il 1 maggio: festa del lavoro; il giorno della festa dei Santi

Apostoli Pietro e Paolo (6); il giorno dell'Assunzione della B. V.

Maria; il giorno di Ognissanti; il 4 novembre: giorno dell'unità

nazionale (7); il giorno della festa dell'Immacolata Concezione;

il giorno di Natale; il giorno 26 dicembre. Art. 3. Sono considerate

solennità civili, agli effetti dell'orario ridotto negli uffici pubblici e

dell'imbandieramento dei pubblici edifici, i seguenti giorni: l'11

febbraio: anniversario della stipulazione del Trattato e del

Concordato con la Santa Sede; il 28 settembre: anniversario della

insurrezione popolare di Napoli.

SEVERAL HOLIDAYS:

October 4 is considered a civil holiday and the day of peace,

brotherhood and dialogue between members of different

cultures and religions, in honor of the special patron saints of

Italy, St. Francis of Assisi and St. Catherine of Siena, pursuant

to Article 3 of the law of 27 May 1949, n. 260.

The law of 27 May 1949, number 260 (Published in the Official

Gazette no. 124 dated 31 May 1949) deals with the disposition

relating to holidays, in addition to the part of Article 3 mentioned

above, [it is early October after all] this law declares the

following are legal holidays: in Article 1: June 2, the date of the

foundation of the Republic of Italy; in Article 2. The following

days, in addition to the national holiday (see Article 1), are

considered public: every Sunday; the first day of the year; the

day of the Epiphany (2); the day of the feast of St. Joseph (3);

April 25, anniversary of the liberation; the Monday after Easter;

the day of the Ascension (4); the day of Corpus Domini (5); May

1st: Labor Day; the day of the feast of the Holy Apostles Peter

and Paul (6); the day of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin

Mary; All Saints' Day; November 4: National Unity Day (7); the

day of the feast of the Immaculate Conception; Christmas Day;

and December 26th. According to Article 3, the following days are

considered civil solemnities, for the purposes of reduced hours in

public offices and the flagging of public buildings: 11 February:

anniversary of the stipulation of the Treaty and the Concordat

with the Holy See; September 28th: anniversary of the popular

uprising in Naples.

Saturday, October 5, 2024

|

|

|

COME SI TRADUCONO “COMPANY/FIRM/BUSINESS” IN ITALIANO?

SI DICE AZIENDA, DITTA, IMPRESA, O SOCIETÀ?

Nel linguaggio quotidiano, i termini “azienda”, “ditta” e “impresa” sono usati

come sinonimi. In realtà, da un punto di vista giuridico, tali termini

definiscono tre concetti ben diversi e distinti. In particolare:

• l’azienda è il complesso dei beni organizzati dall’imprenditore per svolgere

tale attività (art. 2555 Codice Civile) e comprende locali, arredi, macchinari,

attrezzature, ecc.;

• la ditta è la denominazione commerciale dell’imprenditore (art. 2563

Codice Civile), cioè il nome con cui egli esercita l’attività di impresa

distinguendo la propria azienda da quelle concorrenti.

• l’impresa è l’attività svolta dall’imprenditore, e a seconda dei casi può essere

di natura agricola, commerciale o artigiana;

• la società, invece, è un’organizzazione di persone e beni preordinata al

raggiungimento di uno scopo produttivo mediante l'esercizio in comune

diun'attività economica. Può essere definita anche come una forma collettiva di

impresa (vedere Libro V del CodiceCivile, Titolo V), in quanto nella società più

persone - i soci - costituiscono ed esercitano una impresa (vedere art. 2082

Codice Civile ) con lo scopo di ricavarne un guadagno, che poi suddivideranno.

[da bargiornale.it]

HOW DO YOU TRANSLATE “COMPANY/FIRM/BUSINESS” INTO ITALIAN?

DO YOU SAY AZIENDA, DITTA, IMPRESA, OR SOCIETÀ?

In everyday language, the terms “azienda”, “ditta” and “impresa” are used

synonymously. In reality, from a legal point of view, these terms define three

very different and distinctconcepts. In particular:

• l’azienda is the complex of assets organized by the entrepreneur to carry

out this activity (art. 2555 Civil Code) and includes premises, furnishings,

machinery, equipment,etc.;

• la ditta, is the commercial name of the entreprise (art. 2563 Civil Code), i.e.

the name with which the entrepreneur carries out the business activity,

distinguishing his own company from competing ones.

• l’impresa is the activity carried out by the entrepreneur, and depending on

the situation, it can be of an agricultural, commercial or artisanal nature;

• la società, on the other hand, is an organization of people and goods aimed

at achieving a productive purpose through the joint exercise of an economic

activity. It can also be defined as a collective form of enterprise (see Book V of

the Civil Code, Title V), since in the company several people - the partners -

establish and carry out a business (see art. 2082 ofthe Civil Code) with the aim

of obtain a profit, which they will then divide.

[from: bargiornale.it]

Saturday, September 21, 2024

|

|

|

|

GLI AVVERBI GIÀ, APPENA E ANCORA

Questi sono avverbi di tempo. Generalmente, gli avverbi si trovano vicini

alle parole che modificano. L’eccezione a questa regola sono gli

avverbi: già, ancora, e appena.

APPENA riferisce a un’azione conclusa poco tempo prima, in questo

momento. È sinonimo di “poco fa”.

Esempi:

-

Appena arriva Massimiliano, usciamo, ho prenotato un tavolo per le

20:30.

-

Domanda: “Vuoi un caffè?” Risposta: “No grazie, ne ho appena

preso uno.”

-

Ti prego, telefonami appena arrivi a casa, se no mi preoccup.

Nei tempi composti si trova spesso tra l’ausiliare e il participio

passato. L’aereo è appena partito.

E con il futuro anteriore, lo precede. Te lo prometto, ti telefonerò

appena sarò arrivato a casa.

ANCORA riferisce a un’azione non conclusa.

Esempi:

1.Gelsomina non è ancora arrivata, è raro che sia in ritardo, spero che

non le sia successo qualcosa.

2. Domanda: “Vuoi un panino?” Risposta: “Sì grazie, non ho ancora pranzato.

In oltre, ANCORA esprime:

Continuità nel tempo: È tardi, ma qui c’è ancora molto da fare.

Un’altra volta, nuovamente: Ti prego di ripetere ancora quello che hai detto.

Nelle frasi negative, l’evento non è avvenuto, ma dovrebbe avvenire: Marisa

non è ancora arrivata.

Sono disperata, non mi ha ancora telefonato.

Nei tempi composti si trova spesso tra l’ausiliare e il participio passato.

Mario è ancora in ritardo, quando imparerà?

GIÀ riferisce a un’azione conclusa.

Esempi:

-

Ho già letto quel best seller, mi è piaciuto molto.

-

Mario ha già pagato il pranzo, ci ha sorpreso.

- Alessio è già arrivato? Avrà rotto la barriera del suono!

Come vediamo con gli altri avverbi, nei tempi composti si trova spesso

tra l’ausiliare e il participio passato.

The adverbs: GIÀ, APPENA E ANCORA

These are adverbs of time. Generally, adverbs are found close to the

words they modify. The exceptions to this rule are:

appena: as soon as / just: the action ended a very short time ago

ancora: again / still / yet: the action has not ended

già: already / yet / as soon as: the action is completed.

APPENA (as soon as / just) refers to an action completed a short

time ago, at this moment. It is synonymous with "a little while ago".

Examples:

1. As soon as Massimiliano arrives, we go out, I have booked a table

for 8.30 pm.

2. Question: “Do you want a cup of coffee?” Answer: “No thanks, I

just had one.”

3. Please call me as soon as you get home, otherwise I'll worry.

In compound tenses it is often found between the auxiliary and the

past participle. The plane has just left.

And with the future perfect, it precedes it. I promise, I'll call you as

soon as I get home.

ANCORA (again / still / yet) refers to an unfinished action.

Examples:

1. Gelsomina hasn't arrived yet, it's rare for her to be late, I hope

something hasn't happened to her.

2. Question: “Do you want a sandwich?” Answer: “Yes thank you, I

haven't had lunch yet.

Furthermore, ANCORA expresses:

Continuity over time: It's late, but there's still a lot to do here.

Another time, again: Please repeat what you said again.

In negative sentences, the event has not happened, but should happen:

Marisa has not arrived yet.

I'm desperate, she hasn't called me yet.

In compound tenses it is often found between the auxiliary and the past

participle. Mario is still late, when will he learn?

GIÀ (already / yet / as soon as) refers to a completed action.

Examples:

1. I already read that best seller, I liked it a lot.

2. Mario has already paid for lunch, he surprised us.

3. Has Alessio arrived already? He must have broken the sound barrier!

As we see with other adverbs, in compound tenses it is often found

between the auxiliary and the past participle.

Saturday, September 7, 2024

|

|

|

PAROLE INVARIABILI: quelle

che non cambiano dal singolare

al plurale sono di vario genere: |

WORDS THAT DON’T CHANGE:

from singular to plural fall into

various categories: |

DON’T PANIC, JUST PRACTICE!

1. Nomi che terminano con la

vocale accentata: |

1. Words that end with

an accented vowel: |

| la beltà-le beltà |

beauty-beauties |

| il caffè-i caffè |

coffee-coffees |

| la città-le città |

city-cities |

| il paltò -i paltò |

overcoat-overcoats |

| il pascià-i pascià |

pasha-pashas |

| l’università-le università |

university-universities |

| la virtù-le virtù virtue-virtues |

virtue-virtues |

| |

|

[Da questo punto in poi lascio

a voi il compito di pluralizzare—

buon divertimento!] |

[From this point forward, I will

leave the task of pluralizing

up to you—have fun!] |

2. Nomi che terminano in

consonante: |

2. Words that end with a consonant: |

| l’autobus |

bus |

| il bar |

bar |

| il pantheon |

pantheon |

| il parquet |

wood floor |

| lo sport |

sport |

| il tram |

tram |

| il würstel |

hot dog/Vienna sausage |

| |

|

| 3.Nomi e aggettivi monosillabici: |

3. Monosyllabic nouns and adjectives: |

| blu |

blue |

| il dì |

day |

| lo gnu |

gnu |

| la gru |

crane |

| il re |

king |

| il sì |

yes |

| il tè |

tea |

| |

|

| 4. Nomi che terminano in "i": |

4. Words that end with the letter “i”: |

| l’alibi |

alibi |

| l’analisi |

analysis |

| la crisi |

crisis |

| la parentesi |

parenthasis/bracket |

| la sintesi |

synthesis |

| la tesi |

thesis |

| |

|

| 5. Nomi abbreviati: |

5. Shortened words: |

| l’auto |

automobile |

| la bici |

bike |

| il cinema |

cinema |

| la moto |

motorcycle |

| la radio |

radio |

| lo stereo |

stereo |

| |

|

6. Parole straniere: |

|

| |

|

| il drive |

|

| il mouse |

|

| la paella |

|

| il party |

|

| la performance |

|

| il software |

|

| |

|

7. Nomi composti di un

verbo e un sostantivo: |

7. Combination of a verb and a noun: |

| l’asciugacapelli |

hair dryer |

| il cavatappi |

corkscrew |

| il passamontagna |

balaclava |

| il/la portalettere |

mail carrier |

| lo scioglilingua |

tongue-twister |

| il tritacarne |

meat grinder |

Saturday, August 24, 2024 |

|

|

WATERMELON = COCOMERO O ANGURIA?

Fa caldo in Italia d’estate e avete voglia di una fetta di…ma non sapete se si dice

COCOMERO O ANGURIA?

Per una risposta tecnica ci rivolgiamo al CORRIERE DELLA SERA —DIZIONAIRO

“SI DICE ”

-

Si sa che il termine più appropriato, che ripete quello dei botanici, è cocomero,

latinoscientifico Cucumis citrullus; e cocomero si dice in tutta l’Italia centrale,

mentre nell’Italia meridionale l’espressione comune è mellone (o melone)

d’acqua, per distinguerlo dal mellone di pane, quello che tutto il resto d’Italia

chiama semplicemente melone, e in Toscana viene detto anche popone.

-

Anguria è un termine più regionale che invade tutto il Settentrione, con varianti

dialettali notevoli. Per confondere ancor di più le idee, ecco che nella stessa

Lombardiae in vari luoghi del Piemonte e perfino del Mezzogiorno, chiamano

cocomero il cetriolo!

-

Ritornando all’anguria, il nome risale al tardo greco angurion (che indicava

propriamenteil cetriolo), termine venutoci con la dominazione bizantina,

intorno al VI secolo d.C., e diffuso in tutta l’Italia settentrionale attraverso

l’Esarcato di Ravenna. Con referenze storiche così alte, anche anguria ha

dunque pieno diritto di cittadinanza, e possiamo tranquillamente usarlo in

alternativa a cocomero.

It’s hot in Italy during the summer and you are craving a slice of

WATERMELON, but what do you ask for since there are two words that can be

used.

For the answer, we turn to the DICTIONARY “HOW IT IS SAID” from one of the

major Italian newspapers, the CORRIERE DELLA SERA.

-

The most appropriate term, the one that reiterates the botanical one is

cocomero from the scientific Latin Cucumis citrullus; therefore, cocomero is used

throughout central Italy, while in southern Italy the most common expression is

mellone (or melone) d’acqua—watermelon—to differentiate it from the mellone di

pane, that which in therest of Italy is simply called melon, while in Tuscany it is

called popone.

- Anguria is a more regional term that has invaded all of northern Italy, with

notable dialectical variations. To confuse us further, in Lombardy and in various

parts of Piedmont and even in the South, the word cocomero is used for

cucumber.

- Let’s return to anguria, the name dates back to ancient Greek angurion (which

indeed was a cucumber), a word which came to Italy during Byzantine domination

around the 6th CenturyBCE, and spread throughout northern Italy by way of the

Territory of Ravenna. With such highbrow references, even anguria has full rights

of citizenship, and we can use it comfortably as an alternative to cocomero.

Saturday, August 10, 2024

|

|

|

SENTIRE

La volta scorsa abbiamo esaminato ASCOLTARE e SENTIRE.

Però, sentire ha altri usi oltre al senso dell’udito:

1. Il senso del tatto: per esempio: Quando Romeo e Giulietta sono

insieme sentono il battito dei loro cuori.

2. Il senso dell’olfatto: per esempio: Ogni volta che entro in cucina di

mia nonna sento un buon profumo.

3. Il senso del gusto: per esempio: Appena ho assaggiato il sugo, ho

sentito che Irene aveva scambiato lo zucchero per il sale, che disastro!

4. È usato spesso per riportare delle voci su qualcuno o qualcosa. Per

esempio: Hai sentito che Massimiliano e Davide si sono lasciati? Scherzi?

Chissà perché…

5. E per complicare le cose, sentire può anche indicare delle sensazioni o

sentimenti. Per esempio: sentire nostalgia; sentire la mancanza di

qualcuno; sentire dolore, freddo, caldo, ecc.

6. E non dimentichiamo la forma riflessiva, SENTIRSI, che è usata per

esprimere uno stato fisico o psichico. Per esempio: Come ti senti oggi?

Mi sento bene. Loro si sentono a disagio in quell’ambiente.

Vi offro questa bellissima poesia di Alda Marini (Milano, 21 marzo 1931 –

Milano, 1º novembre 2009) è stata una poetessa, aforista e scrittrice

italiana:

Mi piace il verbo sentire

Mi piace il verbo sentire,

sentire il rumore del mare, sentirne l’odore,

sentire il suono della pioggia che ti bagna le labbra,

sentire una penna che traccia sentimenti su un foglio bianco,

sentire l’odore di chi ami,

sentirne la voce e sentirlo col cuore.

Sentire è il verbo delle emozioni,

ci si sdraia sulla schiena del mondo e si sente...

Last time we looked at LISTENING and HEARING.

However, SENTIRE has other uses besides the sense of hearing:

1. The sense of touch: for example: When Romeo and Juliet are together

they feel the beating of their hearts.

2. The sense of smell: for example: Every time I enter my grandmother's

kitchen I smell a good perfume.

3. The sense of taste: for example: As soon as I tasted the sauce, I felt

that Irene had mistaken the sugar for salt, what a disaster!

4. It is often used to report rumors about someone or something. For

example: Did you hear that Massimiliano and Davide broke up? Are you

joking? I wonder why…

5. And to complicate matters, SENTIRE can also indicate sensations or

feelings. For example: feeling nostalgic; to miss someone; feel pain, cold,

heat, etc

6. And let's not forget the reflexive form, SENTIRSI, which is used to

express a physical or mental state. For example: How do you feel today?

I feel well. They feel uncomfortable in that environment.

I offer you this beautiful poem by Alda Marini (Milan, 21 March 1931 –

Milan, 1 November 2009) was an Italian poet, aphorist and writer:

I like the verb to feel

I like the verb to feel,

To hear the sound of the sea, smell it,

To hear the sound of the rain wetting your lips,

To feel a pen trace sentiments on a white sheet of paper,

To smell the smell of the one you love,

To hear his voice and feel him with your heart.

Feeling is the verb of emotions,

You lie on the back of the world and feel...

Saturday, July 27, 2024

|

|

|

ASCOLTARE È DIVERSO DA SENTIRE

ASCOLTARE significa percepire. Si deve concentrare la propria

attenzione sull’interlocutore. È un’azione volontaria. Ti devi mettere nei

panni dell’altra persona, cercare di capire il suo punto di vista. Ascoltare

implica sempre l’uso dell’udito, quindi avvertire un suono, ma con

maggiore attenzione. è fondamentale comprendere fatti, opinioni,

sentimenti altrui.

Per esempio: Mi piace ascoltare la musica classica.

Ascoltami quando ti parlo! Ascoltami quando ti parlo!

Invece, per SENTIRE basta semplicemente usare l'udito per avvertire un

suono o un rumore in maniera involontaria, casuale o superficiale.

Per esempio: Quando il mio vicino accende la radio a volume alto, la

sento attraverso le pareti; ma quando vado a teatro, ascolto con

attenzione l’opera Nabucco, perché mi piace moltissimo la musica di

Giuseppe Verdi.

E non dimentichiamo UDIRE e ORIGLIARE.

UDIRE ha lo stesso significato di sentire, ma è

usato in un registro più formale, raramente usato nella lingua parlata.

ORIGLIARE significa ascoltare di nascosto. Per esempio: Il bambino si era

nascosto dietro la tenda, per origliare i suoi genitori.

La prossima volta esaminiamo gli altri usi di sentire.

TO LISTEN IS DIFFERENT FROM TO HEAR

TO LISTEN means to perceive. You must concentrate your attention on

the interlocutor. It is a voluntary action. You have to put yourself in the

other person's shoes, try to understand their point of view. Listening

always involves the use of hearing, therefore hearing a sound, but with

greater attention. It is essential to understand the facts, opinions and

feelings of others.

For example: I like listening to classical music.

Listen to me when I talk to you! Listen to me when I talk to you!

Instead, TO HEAR you simply need to use your hearing to notice a sound

or noise in an involuntary, random or superficial way.

For example: When my neighbor turns the radio on loudly, I hear it

through the walls; but when I go to the theater, I listen carefully to the

opera Nabucco, because I like Giuseppe Verdi's music very much.

And let's not forget TO HEAR and TO EAVESDROP.

UDIRE (to hear) has the same meaning as SENTIRE (to hear), but is used

in a more formal register, rarely used in spoken language.

TO EAVESDROP means to listen secretly. For example: The child hid

behind the curtain, to eavesdrop on his parents.

Next time let's look at other uses of to hear.

Saturday, July 13, 2024

|

|

|

I METALLI I METALLI

I metalli (in ordine alfabetico) e le loro leghe più comuni sono:

· L’acciaio (leghe ferro-carbonio-cromo-nichel ed altri metalli)-Steel

· L'alluminio (Al)-Aluminum

· L'argento (Ag)-Silver

· Il bronzo (lega rame-stagno, ma anche -alluminio, -nichel, -berillio)

-Bronze -Bronze

· Il ferro (Fe)-Iron

· Il mercurio (Hg)-Mercury

· L'oro (Au)-Gold

· L'ottone (lega rame-zinco, con aggiunta di Ferro, Stagno, ed altri

metalli)-Brass metalli)-Brass

· Il platino (Pt)-Platinum

· Il piombo (Pb)-Lead

· Il rame (Cu)-Copper

· Lo stagno (Sn)-Tin

· Il titanio (Ti)-Titanium

· Lo zinco (Zn)-Zinc

The most common metals (in alphabetical order)

and their alloys are:

Aluminum-Alluminio

Brass-Ottone (combines copper and zinc, with addition of iron, tin, and

other metals) other metals)

Bronze-Bronzo (combines copper and tin, but also with aluminum,

nickel, beryllium) nickel, beryllium)

Copper-Rame

Iron-Ferro

Gold-Oro

Lead-Piombo

Mercury-Mercurio

Platinum-Platino

Silver-argento Steel-acciaio (combines iron, carbon, chrome, nickel,

and other metals) and other metals)

Tin: stagno

Titanium-Titanio

Zinc-Zinc

Saturday, June 29, 2024

|

|

|

CHICCO o GRAPPOLO D’UVA

Il sostantivo collettivo “uva” che descrive un grappolo invece di un chicco o

acino, confonde facilmente. Perciò passiamo alla definizione e all’uso di

CHICCO.

An edible seed or cereal grain, or seeds from other plants: a grain of An edible seed or cereal grain, or seeds from other plants: a grain of

wheat, of barley, a kernel of corn, a grain of rice, a coffee bean, a

pomegranate seed, a grape;

A small spherical or rounded object: hailstones, the beads on a rosary A small spherical or rounded object: hailstones, the beads on a rosary

(also called a crown); the beads on a coral necklace;

A term of endearment for proper names such as Federico, Enrico and A term of endearment for proper names such as Federico, Enrico and

Francesco;

By extension, it is generally a spontaneous and friendly name used by By extension, it is generally a spontaneous and friendly name used by

family members for a person they value and love; and

In Tuscan it is the same as chicca. In Tuscan it is the same as chicca.

Saturday, June 15, 2024

|

|

|

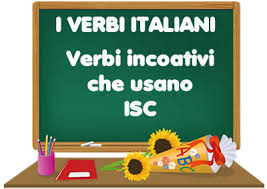

VERBI INCOATIVI—Parte 3

TERZA CONIUGAZIONE CON -ISC-

Questi verbi sono coniugati come FINIRE (fin-ìre)

| |

IO |

TU |

LUI/LEI |

NOI |

VOI |

LORO |

| 1. |

finìsco |

finìsci |

finìsce |

finiàmo |

finìte |

finìscono |

| 2. |

finìvo |

finìvi |

finìva |

finivàmo |

finivàte |

finìvano |

| 3. |

finìi |

finìsti |

finì |

finirémo |

finìste |

finìrono |

| 4. |

finirò |

finirài |

finirà |

finirémo |

finiréte |

finirànno |

| 5. |

finìsca |

finìsca |

finìsca |

finiàmo |

finiàte |

finìscano |

| 6. |

finìssi |

finìssi |

finìsse |

finìssimo |

finìste |

finìssero |

| 7. |

finirèi |

finirésti |

finirébbe |

finirémmo |

finiréste |

finirébbero |

| 8. |

|

finìsci |

[finìsca] |

finiàmo |

finìte |

[finìscano] |

1= presente indicativo; 2=imperfetto; 3=passato remoto; 4=futuro semplice;

5=congiuntivo presente; 6=congiuntivo imperfetto; 7=condizionale semplice;

8=imperativo.

Ciò che segue è parte della lista dei verbi incoativi che vi ho promesso la volta

scorsa, con il loro significato in inglese.

1= present indicative; 2=imperfect; 3=remote past/past absolute; 4=simple

future; 5=present subjunctive; 6=imperfect subjunctive; 7=simple conditional;

8=imperative.

These verbs are conjugated like FINIRE above.

What follows is part of the list of inchoative verbs that I promised you last time,

with their English meaning.

------------------------------------------------------

L |

| lambire-sfiorare |

largire-bestow/lavish |

lenire-soothe/relieve |

| M |

| marcire-rot |

muffire-mold |

munire-equip/arm |

| N |

| nitrire-neigh/whinny |

| O |

| obbedire-obey |

ordire-scheme/hatch plot |

ostruire-obstruct |

| P |

| partorire-give birth |

premunire-equip |

| patire-depart |

presagire-foretell |

| pattuire-negotiate/agree |

prestabilire-prearrange |

| percepire-perceive |

proferire-say/utter |

| perire-perish |

progredire-avance |

| perquisire-search |

proibire-forbid |

| polire-polish marble |

prostituire-prostitute |

| poltrire-laze about |

pulire-clean |

| preferire-prefer |

punire-punish |

| R |

| rabbonire-calm/mollify |

requisire-confiscate |

rimpicciolire-make smaller |

| rabbrividire-shiver |

restituire-return |

rincitrullire-make crazy |

| raddolcire-sweeten |

retribuire-pay |

rincretinire- make crazy |

| raggranchire-curl up |

ribadire-conferm |

rincurvire-curve |

| raggrinzire-wrinkle/crumble |

ricostituire-reconstitute |

rinfoschirsi-obfuscate |

| rammollire-soften |

ricostruire-rebuild |

ringalluzzire-perk up |

| rannerire-blacken |

riferire-report/tell |

ringiovanire-rejuvenate |

| rapire-sequester |

rifinire-complete |

rinsanire-become sane again |

| rattrappire-numb/addle |

rifiorire-thrive/rebloom |

rinsavire-regain senses |

| rattristire-sadden |

rifluire-ebb tide |

rinsecchire-lose weight |

| reagire-react |

rifornire-supply |

rinverdire-revive |

| recensire-review |

rimbaldanzire-embolden |

rinvigorire-reinvigorate |

| recepire-adopt |

rimbambire-frazzle |

ripulire-reclean |

| redarguire-reprimand |

rimbambolire-daze |

rcire-indemnify |

| redimere-redeem |

rimbecillire-make stupid |

risecchire-dry up |

| regredire-regress |

rimbiondire-make blond |

ristabilire-re-establish |

| reinserire-reinsert |

rimboschire-reforest |

riunire-reunite |

| reperire-find/trace |

rimminchionire-make stupid |

riverire-respect |

| S |

| sancire-bring about |

mentire-contradict |

| sbalordire-surprise |

sminuire-reduce |

| sbandire-exile |

snellire-slim down |

| sbiadire-fade |

sopire-calm |

| sbianchire-bleach |

sopperire-provide |

| sbigottire-shock |

sorbire-sip |

| sbizzarrire-indulge |

sostituire-substitute |

| scalfire-scratch |

sparire-vanish |

| scaltrire-sharpen/hone |

spaurire-terrify |

| scandire-scan verses |

spazientire-lose patience |

| scarnire-deflesh |

spedire-send/mail |

| scaturire-originate |

squittire-squeak/squeal |

| schermire-to fence |

stabilire-establish |

| schernire-taunt/mock |

starnutire-sneeze |

| schiarire-lighten |

statuire-decree |

| scolorire-discolor |

stecchire-kill outright |

| scolpire-sculpt |

sterilire-sterilze |

| scurire-darken |

stiepidire-make tepid |

| sdilinquire-become sentimental |

stizzire-anger |

| seppellire-bury |

stordire-stun |

| sfinire-tire |

stormire-rustle |

| sfiorire-lose petals/fade |

striminzire-make thin |

| sfittire- thin out |

stupire-surprise |

| sfoltire-thin out |

subire-endure |

| sfornire-unfurnish |

suggerire-suggest |

| sgranchire-stretch |

supplire-compensate |

| sgualcire-rumple/crease |

svampire-evaporate |

| sguarnire-remove trim |

svanire-vanish |

| smagrire-lose weight |

sveltire-smarten |

| smaltire-digest |

svigorire-less vigor |

| smarrire-lose |

svilire-devalue |

| T |

| tintinnire-jingle |

trasalire-startle |

| tornire-work the lathe |

trasferire-transfer |

| tradire-betray |

trasgredire- transgress |

| tramortire-knock out |

tripartire-divide in 3 |

| U |

|

| ubbidire-obey |

unire-unite |

usufruire-enjoy |

| V |

| vagire-newborn’s cry |

| Z |

| zittire-hush |

VERBI INCOATIVI—Parte 2

TERZA CONIUGAZIONE CON -ISC-

Questi verbi sono coniugati come FINIRE (fin-ìre)

| |

IO |

TU |

LUI/LEI |

NOI |

VOI |

LORO |

| 1. |

finìsco |

finìsci |

finìsce |

finiàmo |

finìte |

finìscono |

| 2. |

finìvo |

finìvi |

finìva |

finivàmo |

finivàte |

finìvano |

| 3. |

finìi |

finìsti |

finì |

finirémo |

finìste |

finìrono |

| 4. |

finirò |

finirài |

finirà |

finirémo |

finiréte |

finirànno |

| 5. |

finìsca |

finìsca |

finìsca |

finiàmo |

finiàte |

finìscano |

| 6. |

finìssi |

finìssi |

finìsse |

finìssimo |

finìste |

finìssero |

| 7. |

finirèi |

finirésti |

finirébbe |

finirémmo |

finiréste |

finirébbero |

| 8. |

|

finìsci |

[finìsca] |

finiàmo |

finìte |

[finìscano] |

1= presente indicativo; 2=imperfetto; 3=passato remoto; 4=futuro semplice;

5=congiuntivo presente; 6=congiuntivo imperfetto; 7=condizionale semplice;

8=imperativo.

Ciò che segue è parte della lista dei verbi incoativi che vi ho promesso la volta

scorsa, con il loro significato in inglese.

1= present indicative; 2=imperfect; 3=remote past/past absolute; 4=simple

future; 5=present subjunctive; 6=imperfect subjunctive; 7=simple conditional;

8=imperative.

These verbs are conjugated like FINIRE above.

What follows is part of the list of inchoative verbs that I promised you last time,

with their English meaning.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

|

| A |

| abbellire-beautify |

aggrinzire-wrinkle |

appiattire-flatten |

| abbonire-placate |

agguerrire-fortify |

approfondire-deepen |

| abbonire-placate |

agire-act |

appuntire-sharpen |

| abbrunire-to tan |

alleggerire-lighten |

ardire-dare |

| abbrustolire-sear |

allestire-prepare |

arricchire-enrich |

| abbrutire-like a brute |

allibire-appall |

icharrochire-become raspy |

| abbruttire-make ugly |

ambire-crave/yearn |

arrossire-redden |

| abolire-abolish |

ammalizzire-malicious |

arrostire-roast |

| abolire-abolish |

ammannire-prepare |

arrugginire-rust |

| abortire-abort |

ammansire-calm/tame |

assalire-assault |

| accalorire-heat up |

ammattire-go crazy |

assaporire-flavor |

| accalorire-heat up |

ammezzire-half |

assentire-agree |

| accanire-enrage |

ammollire-soak |

asserire-state |

| accudire-look after |

ammonire-admonish |

asservire-enslave |

| acquisire-obtain |

ammorbidire-soften |

assonnire-get sleepy |

| acuire-sharpen |

ammortire-lethargic |

assopire-doze off |

| addolcire-sweeten |

ammoscire-flacid/soft |

assordire-deafen |

| adempire-fulfill |

ammuffire-mold |

assortire-to sort |

| aderire-adhere |

ammusire-frown/pout |

attecchire-take root |

| adibire-assign |

ammutire-silence |

atterrire-terrify |

| affievolire-abate |

ammutolire-silence |

attribuire-attribute |

| affiochire-weaken |

annerire-blacken |

attristire-sadden |

| affittire-thicken |

annichilire-annihilate |

attutire-muffle/alleviate |

| affluire-flow |

annuire-nod |

avvilire-depress/sad |

| aggobbire-hunchback |

appassire-wilt |

avvizzire-wilt |

| aggranchire-numb |

appesantire-weigh down |

azzittire-silence |

| aggredire-attack |

appetire-desire much |

| B |

| bandire-announce |

bramire-growl |

| barrire-trumpet |

brandire-brandish |

| bipartire-two party |

brusire-hubbub/buz |

| C |

| campire-background |

compire-conclude |

| capire-understand |

concepire-conceive |

| carpire-purloin |

concupire-desire |

| censire-census |

condire-season/mix |

| chiarire-lighten |

conferire-confer |

| circuire-deceive |

confluire-flow into/merge |

| cogestire-comanage |

contribuire-contribute |

| colorire-color |

costituire-constitute |

| colpire-strike/hit |

costruire-build |

| compatire-pity |

custodire-safeguard |

| D |

|

| deferire-refer |

diluire-dilute |

| definire-define |

dimagrire-lose weight |

| defluire-drain away |

diminuire-lessen |

| deglutire-swallow |

dipartire-divide in two |

| demolire-demolish |

disquisire-discorse |

| deperire-waste away |

disseppellire-unearth |

| differire-defer |

distribuire-distribute |

| digerire-digest |

disubbidire-disobey |

| digredire-digress |

disunire-take apart |

| E |

| eccepire-to object |

esaurire-use up |

| effluire-flow |

esibire-exhibit |

| erudire-teach |

esordire-commence |

| esaudire-fulfill/grant |

esperire-experiment |

| F |

| fallire-fail |

fluire-flow |

| farcire-stuff a cavity |

forbire-clean |

| favorire-favor |

fornire-furnish |

| ferire-wound |

frinire-chirp/cicada |

| finire-end |

fruire-enjoy |

| fiorire-flower |

| G |

|

| garantire-guarantee |

gremire-crowd |

| garrire-wave a flag |

grugnire-grunt |

| gestire-manage |

guaire-yelp/whimper |

| ghermire-grip/clasp |

gualcire-wrinkle |

| gioire-rejoyce |

guarire-cure |

| gradire-enjoy |

guarnire-garnish |

| graffire-make graffiti |

guattire-dog’s bark |

| I |

| illanguidire-weaken |

incancrenire-gangrene/entrench |

| illiquidire-liquify |

incanutire-go white |

| illividire-black & blue |

incaparbire-become stubbord |

| imbaldanzire-grow bold |

incaponire-insistere |

| imbambinire-child-like gestures |

incarnire-embody |

| imbandire-prep a banquet |

incarognire-get angry |

| imbarbarire-barbarianize |

incartapecorire-shrivel up |

| imbarbogire-frazzle |

incattivire-get nasty |

| imbarbarire-corrupt/debase |

incenerire-incinerate |

| imbastire-baste/sew |

incitrullire-become stupid |

| imbellire-beautify |

incivilire-civilize |

| imbestialire-enrage |

incollerire-to anger |

| imbianchire-whiten |

incrudelire-make cruel |

| imbiondire-lighten hair |

incrudire-make crude |

| imbizzarrire-agitate/horse |

incupire-to cloud/sadden |

| imbizzire-craze/horse |

incuriosire-intrigue/interest |

| imbolsire-horse asthmatic |

incurvire-curve a person |

| imbonire-shill |

indebolire-weaken |

| imborghesire-gentrify |

indiavolire-cruel/mean |

| imboschire-forest |

indispettire-irritate |

| imbottire-stuff |

indolcire-sweeten |

| imbrunire-darken/dusk |

indolenzire-make sore |

| imbrutire-brute-like |

indurire-harden |

| imbruttire-make ugly |

inebetire-stupefy |

| immalinconire-sadden |

infarcire-fill/stuff |

| immiserire-impoverish |

infastidire-bother |

| impadronirsi-sieze |

infeltrire-pound like felt |

| impallidire-become pale |

inferire-inflict |

| impartire-impart |

inferocire-enrage |

| impaurire-frighten |

infervorire-zeal |

| impazzire-make crazy |

infiacchire-enfeeble |

| impedire-impede |

infierire-be cruel/rub in |

| impensierire-worry |

infittire-intensify/thicken |

| impermalire-to offend |

influire-influence |

| impietrire-petrify |

infoltire-thicken |

| impiantire-tile a floor |

informicolirsi-prickly |

| impicciolire-make smaller |

infoschirsi-grim/darken |

| impiccolire- reduce |

infracidire-rot/soak |

| impietosire-move to pity |

infreddolire-get cold |

| impigrire-make/grow lazy |

infrollire-become high |

| impinguire-get super fat |

infurbire-shrewd/cunning |

| impoltronire-become lazy |

ingagliardire-invigorate |

| impratichire-gain practice |

ingelosire-make jealous |

| impreziosire-embellish |

ingentilire-refine/civilize |

| impuntire-to quilt |

ingerire-ingest |

| imputridire-rot/putrefy |

ingiallire-turn yellow |

| impuzzolentire-stink up |

ingigantire-exaggerate/magnify |

| inacerbire-exacerbate/embitter |

ingobbire-hunchback |

| inacetire-become acidic |

ingolosire-make mouth water |

| inacidire-acidify |

ingrandire-enlarge |

| inaridire-dry up/arid |

ingrugnire-scowl |

| inasprire-embitter/worsen |

inibire-inhibit/hinder |

| incadaverire-decompose |

innervosire-annoy/stress |

| incallire-callus |

inorgoglire-make proud |

| incanaglire-become malicious |

inorridire-horrify |

|

| inquisire-investigate |

intumidire-swell up |

| insanire-become crazy |

inturgidire-swell |

| insaporire-season/flavor |

inumidire-dampen |

| inselvatichire-make unsociable |

invaghirsi-take a fancy to |

| inserire-insert |

inveire-inveigh/denounce |

| insignire-honor with |

invelenire-jaundice/poison |

| insipidire-lose flavor |

inverdire-green |

| insolentire-insult/offend |

inverminire-verminelike |

| insospettire-arouse suspicion |

invetrire-glasslike |

| insuperbire-make arrogant |

invigorire-invigorate |

| intenerire-tenderize/soften |

invilire-debase |

| interagire-interact |

inviperire-infuriate |

| interferire-interfere |

involgarire-make vulgar |

| interloquire-interrupt |

irrancidire-turn rancid |

| intestardirsi-insist/obstinent |

irretire-entrap |

| intiepidire-make tepid |

irrigidire-stiffen |

| intimidire-scare/intimidate |

irrobustire-build up |

| intimorire-scare/frighten |

irruvidire-roughen |

| intirizzire-numb w/cold |

ischeletrire-skeletal |

| intontire-daze |

ispessire-thicken |

| intorbidire-roil |

isterilire-make infertile/dry up |

| intorpidire-numb/sluggish |

istituire-establish |

| intozzire-stocky/squat |

istruire-instruct |

| intristire-sadden |

istupidire-make stupi |

| intuire-intuit |

|

Saturday, May 18, 2024

|

|

| |

Che cosa sono i verbi incoativi?

Parte 1, introduzione generale: per le prossime settimane vi fornirò una lunga

lista di questi verbi con le loro traduzioni in inglese. Il mio conisglio, è di

trovane alcuni che vi piacciono, usateli in una frase, e così non li dimenticherete.

Buon divertimento!

Secondo la grammatica Treccani sono: “I verbi della III coniugazione che

presentano l’inserimento dell’➔interfisso -isc- tra la ➔radice e la ➔desinenza.

Quest’ampliamento avviene solo in alcune voci. Si tratta di un fenomeno

caratteristico solo della terza coniugazione; ed è presente nella maggioranza dei

suoi verbi.

• Nella 1a e 2a persona singolare e nella 3a persona singolare e plurale

dell’indicativo presente

fin-isc-o, cap-isc-i, prefer-isc-e, contribu-isc-ono

• Nella 1a e 2a persona singolare e nella 3a persona singolare e plurale del

congiuntivo presente

defin-isc-a, favor-isc-a, obbed-isc-a, sment-isc-ano

• Nella 2a persona singolare e 3a persona singolare e plurale dell’imperativo

inser-isc-i!, guar-isc-a!, reag-isc-ano!”

Se cerchiamo il significato del termine incoativo, scopriamo di nuovo in Treccani,

che è un aggettivo “che esprime l’inizio di un’azione o di un modo di essere;

usato soltanto nella terminologia grammaticale; come per esempio il latino

senescĕre «cominciare a invecchiare», vesperascĕre «farsi sera».”

Nonostante la base latina che aveva una funzione specifica, cioè di indicare

l’inizio di un’azione, in italiano l’interfisso –isc non ha nessun valore semantico,

in fatti non c’è nessuna differenza di significato tra annero e annerisco.

What are inchoative verbs?

Part 1: introduction: for the next few weeks I will provide you with a long list

of these verbs with their English translations. My advice is to choose verbs that

you find pleasing, use them in a sentence, this way you won’t forget them.

Have fun!

According to the Treccani grammar, they are: “Verbs of the 3rd conjugation which

require the insertion of the interface –isc between the root and the ending. This

extension occurs only in certain entries. This phenomenon is found only is the

verbs of the third conjugation and appears in the majority of them.

- The 1st and 2nd person singular and the 3rd person singular and plural of

the present indicative

fin-isc-o, cap-isc-i, prefer-isc-e, contribu-isc-ono

- The 1st and 2nd person singular and the 3rd person singular and plural of

the present subjunctive

defin-isc-a, favor-isc-a, obbed-isc-a, sment-isc-ano

- The 2nd person singular and the 3rd person singular and plural of the

imperative

inser-isc-i!, guar-isc-a!, reag-isc-ano!”

If we search for the meaning of the term inchoative, we discover, again in

Treccani, that it is an adjective “that expresses the beginning of an action or of

a state of being; it is used solely in grammar terminology; to express in Latin

senescĕre «begin to age>>, vesperascĕre «become evening>>. Notwithstanding

its Latin base that had a specific function, that is to indicate the onset of an

action, in Italian the interface –isc has no semantic value, in fact there is no real

difference in meaning between annero and annerisco (to blacken).

Saturday, May 4, 2024

|

|

|

25 aprile: Anniversario della liberazione d'Italia dal nazifascismo

Il 25 aprile, in Italia si celebra la festa della Liberazione dal nazifascismo.

L’occupazione tedesca e fascista in Italia non terminò in un solo giorno, ma si

considera il 25 aprile come data simbolo perché nel 1945 coincise con l’inizio

della ritirata da parte dei soldati della Germania nazista e di quelli fascisti della

repubblica di Salò dalle città di Torino e di Milano, dopo che la popolazione si

era ribellata e i partigiani avevano organizzato un piano coordinato per

riprendere il controllo delle città.

L'istituzione della festa nazionale: Su proposta del Presidente del Consiglio

Alcide De Gasperi, il Principe Umberto, allora Luogotenente del Regno d'Italia,

istituì la festa per il 1946, con il decreto legislativo luogotenenziale n. 185 del

22 aprile 1946 ("Disposizioni in materia di ricorrenze festive"), pubblicato nella

Gazzetta Ufficiale del Regno d'Italia nr. 96 di mercoledì 24 aprile 1946;

l'articolo 1 infatti recitava: «La celebrazione della totale liberazione del

territorio italiano, il 25 aprile 1946 è dichiarato festa nazionale.»

La data fu fissata in modo definitivo con la legge n. 269 del maggio 1949,

presentata da De Gasperi in Senato nel settembre 1948. Da allora, il 25 aprile

è un giorno festivo, come le domeniche, il primo maggio, il giorno di Natale e la

festa della Repubblica, che ricorre il 2 giugno. La guerra in Italia non finì

precisamente il 25 aprile 1945, comunque: continuò ancora per qualche giorno,

fino agli inizi di maggio.

Perché il 25 aprile si festeggia la Liberazione - Il Post

April 25th: Anniversary of the Liberation of Italy from Nazism and Fascism

On April 25th, Italy celebrates its liberation from Nazism and Fascism. The

German and Fascist occupation in Italy did not end in a single day, but April

25th is considered a symbolic date because in 1945 it coincided with the

beginning of the retreat by the soldiers of Nazi Germany and the Fascist

soldiers of the Republic of Salò from the cities of Turin and Milan, after the

people of those cities had rebelled and the partisans had organized a

coordinated plan to regain control of those areas.

The establishment of this national holiday: As the result of the proposal of the

Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi, Prince Umberto II, then Lieutenant of the

Kingdom of Italy, established the holiday in 1946, through the Lieutenant

Legislative decree n. 185 of April 22, 1946 ("Provisions regarding festive

occasions"), which was published in the Official Gazette of the Kingdom of

Italy n. 96 of Wednesday, April 24, 1946; Article 1 in fact stated: «To celebrate

the total liberation of the Italian territory, April 25, 1946 was declared a

national holiday.»

The date was definitively established by means of the law no. 269 of May 1949,

presented by De Gasperi to the Senate in September 1948. Since then, April

25th has been a public holiday, like Sundays, May 1st, Christmas Day and the

Celebration of the creation of the Republic of Italy, which occurs on June 2nd.

The war in Italy did not end precisely on April 25, 1945; it continued for a few

more days, until the beginning of May.

Saturday, April 20, 2024

|

|

Quante volte i miei studenti sbagliano dicendo “SERIOSO” per l’inglese SERIOUS,

invece dovrebbero dire SERIO, SEVERO, GRAVE, ecc.

Come possiamo tradurre SERIOUS? Ecco alcuni esempi:

- Lo studente vide l’espressione severa del professore, e capì di essere nei

guai.

- Per fortuna il medico ha detto a Ilaria che non era una situazione grave.

- Quante volte te lo devo dire, non sto scherzando, sono seria.

- L’omicidio è un reato grave.

- Questa volta papà è serissimo, Clara è rientrata a casa tardi dopo il

coprifuoco, adesso non può uscire con le sue amiche per un mese.

- Era una situazione delicata, e Gelsomina l’ha affrontata come se fosse

niente.

- Il manager ha un colloquio impegnativo questo pomeriggio, teniamoci alla

larga da lui.

At times my students are mistaken when the say “SERIOSO” for the English

SERIOUS, they should say SERIO, SEVERO, GRAVE, etc.

How we can translate SERIOUS? Here are a few examples:

- The student saw the professor’s serious expression, and understood that

he was in trouble.

- Luckily the doctor told Hillary that is wasn’t a serious situation.

- How many times do I have to tell you, I’m not joking, I’m serious.

- Homicide is a serious offense.

- This time Dad is dead serious, Claire come home late after her curfew,

now she can’t go out with her friends for a month.

- It was a serious situation, and Gelsonima confronted it as if it were

nothing.

- The manager has a serious meeting this afternoon, let’s give him wide

berth.

|

| |

Saturday, April 6, 2024

|

|

Crutch = stampella o gruccia = hanger = attaccapanni?

Dobbiamo stare attenti alle traduzioni corrette!

Crutch si può tradurre come:

- Una gruccia o una stampella—spesso al plurale:

Per esempio: La settimana scorsa uno dei miei studenti è scivolato sul

ghiaccio; adesso cammina con le stampelle (o le grucce) perché ha una

gamba rotta.

- Un appoggio o un sostegno—uso figurato o psicologico:

Per esempio: Penso che tu stia usando la tua famiglia come sostegno.

Ma se guardiamo all’inverso, le stampelle o le grucce sono anche usate per

appendere i panni.

Per esempio: Carlo, per favore, passami una stampella (o una gruccia)

per appendere questa camicia.

In questo caso, si può usare “attaccapanni” invece di stampella o gruccia.

Crutch = stampella or gruccia = hanger = attaccapanni?

We must pay attention to the correct translations!

Crutch may be translated as:

- Gruccia or stampella—often in the plural:

For example: Last week one of my students slipped on the ice; now he

walks with crutches (grucce or stampelle) because he has a broken leg.

- Appoggio or sostegno—in a figurative or psychological sense:

For example: I believe you are using your family as a crutch. (sostegno or

appoggio)

If we look at the opposite however, stampelle or grucceare also used to hang

clothes.

For example: Carlo, please pass me a hanger (gruccia or stampella) to

hang up this shirt.

In this case, we can use the word “attaccapanni” instead of gruccia or stampella

for a clothes hanger.

Saturday, March 23, 2024

|

|

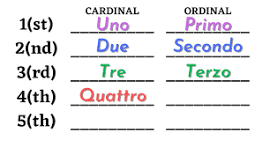

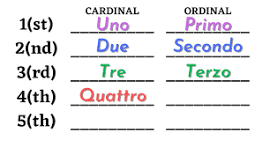

I NUMERI ORDINALI (1°, 2°, 3°…) E CARDINALI (1, 2, 3…)

Per qualche ragione, gli studenti si trovano con la bocca impastata quando

devono leggere i numeri ad alta voce.

Perciò facciamo un piccolo ripasso; i numeri ordinali:

- Indicano la posizione o l'ordine di successione rispetto ad altri numeri:

primo, secondo, terzo, ecc.

- Sono variabili nel genere (maschile o femminile) e nel numero (singolare o

plurale); per esempio: il primo giorno del mese, la prima volta che sono

andata in Italia, i primi libri che ho letto, le prime lettere che ho scritto.

- I primi dieci hanno una forma particolare: primo, secondo, terzo, quarto,

quinto, sesto, settimo ottavo, nono, decimo.

- I successivi si formano aggiungendo il suffisso -esimo al numero cardinale,

che di solito perde la vocale finale: undici=> undicesimo, quindici=> quindi

cesimo, cento=> centesimo; ma ventitré=> ventitreesimo, trentatré =>

trentatreesimo.

- Altri esempi: quattrocentesimo, millesimo, milionesimo, miliardesimo, ecc.

- Sono abbreviati:

- Con i numeri romani (in particolare per i secoli, i papi, i re e le regine):

Dante morì a Ravenna nel XIV [quattordicesimo] secolo, Papa Giovanni

XXIII [ventitreesimo], Re Vittorio Emanuele III [terzo], la Regina

Elisabetta II [seconda].

- Con una piccola "o" (per il maschile singolare), una piccola "a" (per il

femminile singolare), una piccola "i" (per il maschile plurale), e una piccola

"e" (per il femminile plurale); soprascritte; per esempio: 1o= primo, 1a =

prima, ecc.

Si prega di notare: Per i giorni del mese, in italiano, usiamo i numeri cardinali,

con l'eccezione del primo giorno che è sempre ordinale, per esempio: ventidue

luglio, tredici agosto, ma primo novembre.

ORDINAL NUMBERS (1st, 2nd, 3rd…) and CARDINAL NUMBERS (1, 2, 3…) ORDINAL NUMBERS (1st, 2nd, 3rd…) and CARDINAL NUMBERS (1, 2, 3…)

r some reason, students find themselves tongue-tied when they have to read

numbers out loud.

Therefore, let’s review them; ordinal numbers: OK

- Indicate position or order in relation to other numbers: first, second, third,

etc.

- In Italian they vary according to gender (masculine or feminine) and

number (singular or plural); in English there is no difference; for example:

the first day of the month (“giorno” is a masculine singular word, thus

“primo”), the first time I went to Italy (“volta” is a feminine singular word,

thus “prima”), the first books I read (“libri” is a masculine plural word, thus

“primi”), the first letters I wrote (“lettere” is a feminine plural word, thus

“prime”).

- The first ten have a particular form: first, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth,

seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth.

- The following numbers are formed by adding the suffix -esimo to the

cardinal number which usually drops the final vowel: undici=> undicesimo,

quindici=> quindicesimo, cento=> centesimo, but ventitré=>

ventitreesimo, trentatré => trentatreesimo.

- Other examples: four hundredth, thousandth, millionth, billionth, etc.

- Are abbreviated:

- with roman numerals (particularly for centuries, popes kings and queens):

Dante died in Ravenna in the 14th century, Pope John XXIII, King Victor

Emanuel III, Queen Elizabeth II.

- with a small "o" (for masculine singular), with a small "a" (for feminine

singular), with a small "i" (for masculine plural), and with a small "e" (for

feminine plural); for example: 1o= first (masculine singular), 1a = first

(feminine singular), etc.

Please note: For the days of the month, in Italian, we use the cardinal numbers,

with the exception of the first day which is always an ordinal number, for

example: twenty two July, thirteen August, but first November (not July 22nd,

August 13th, November 1st.)

Saturday, March 9, 2024

|

|

CERVELLO O CERVELLA?

Di nuovo ci rivolgiamo all’Enciclopedia Treccani per la risposta ed esempi.

La parola cervello ha due plurali:

- Il plurale maschile cervelli ha gli stessi usi del singolare, anche figurati.

Esempi:

Le scoperte dei ricercatori italiani all’estero: un effetto della fuga di cervelli.

Cervelli elettronici dotati di una memoria straordinaria.

- La forma femminile cervella,

- Invece, indica specificamente ‘la materia di cui si compone il cervello’.

Si usa soprattutto in espressioni idiomatiche.

Esempio:

Farsi saltare le cervella (= uccidersi con un colpo d’arma da fuoco alla

testa)

- Inoltre, specie in alcune regioni, è usato in riferimento al cervello

degli animali macellati e alle specialità gastronomiche che se ne

ricavano.

Esempi:

Cervella d’agnello

Un piatto di cervella* fritte.

https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/cervelli-o-cervella

BRAINS

What is the correct form for “Brains” in Italian? We again turn to the

Encyclopedia Treccani for answers and examples.

The word brain has two plurals.

- The masculine plural Cervelli has the same uses as the singular, even

figuratively.

Examples:

The discovery of Italian researchers abroad: an effect of brain-drain.

Electronic brains equipped with an extraordinary memory.

- The feminine plural cervella,

- On the other hand, specifically refers to ‘the matter of which the brain

is made'. It is used primarily in idiomatic expressions.

Example:

Blow one’s brains out (kill oneself with a bullet to the head).

- Additionally, especially in certain regions of the country, it is used to

refer to the brains of butchered animals and the gastronomical

specialties they produce.

Examples:

Lambs’ brains.

A dish of fried brains*.

*per i vegetariani tra di voi, spero di non aver offeso // for the vegetarians

among you, I hope I haven’t offended.

Saturday, February 24, 2024

|

|

| |

Abbiamo esaminato il verbo PENSARE con le preposizioni A e DI. Ma non

dimentichiamo la congiunzione CHE.

Ci sono due cose importanti da ricordare:

- Quando si usa il verbo PENSARE per esprimere un pensiero che si ha,

riguardo a qualcun altro o qualcosa d’altro, la congiunzione CHE deve

seguire il verbo. In una frase italiana di questo tipo, CHE serve per

collegare due locuzioni separate, la parola “che” non può mancare (cosa

che in inglese non avviene).

- CHE poi è seguita da un verbo al congiuntivo, che darà inizio alla frase che

segue, per descrivere a cosa o a chi sta pensando il soggetto.

Pensare + che + verbo al congiuntivo (presente, passato, imperfetto,

trapassato)

Esempi:

- Paola pensa che Francesco sia l’uomo più bello che abbia mai visto. La

verità è che ha dimenticato gli occhiali a casa. [verbo al presente del

congiuntivo]

- Ilaria pensa che Giacomino sia andato a casa presto in taxi. [verbo al

passato del congiuntivo]

- Barbara pensava che ieri fosse il giorno più felice della sua vita. [verbo

all’imperfetto del congiuntivo]

- Daniele pensava che Stefania fosse tornata a casa dei suoi subito dopo la

festa. [verbo al trapassato del congiuntivo]

We looked at the verb PENSARE with the prepositions A and DI. Let’s not

forget the conjunction CHE.

There are two important things to remember:

- When one uses the verb PENSARE to express a thought regarding

someone or something else, the conjunction CHE follows the verb. In an

Italian sentence of this kind, CHE is used to connect two separate phrases,

the word “che” cannot be left out—something that doesn’t occur in English.

- CHE is then followed by a verb in the subjunctive mood, which will begin

the phrase that follows, and describes who or what the subject is thinking

about.

Pensare + che + verb in the subjunctive (present, past, imperfect, past perfect)

Examples:

- Paola thinks that Francesco is the most handsome man she has ever seen.

The truth is that she forgot her glasses at home. [verb in Italian is in the

present subjunctive]

- Hillary thinks that James went home early in a taxi. [verb in Italian is in

the past subjunctive]

- Barbara thought yesterday was the happiest day of her life. [verb in Italian

is in the imperfect subjunctive]

- Daniel thought that Stephanie had returned home to her folks’ house

immediately after the party. [verb in Italian is in the past perfect

subjunctive]

Saturday, February 10, 2024

|

|

PENSARE A O PENSARE DI: QUAL È LA PREPOSIZIONE GIUSTA?

Pensare “a”

Il verbo pensare è seguito dalla preposizione “a” davanti a un sostantivo o un

pronome; pensare a qualcuno o a qualcosa. Può essere usato al presente,

passato o futuro.

Pensare + a + sostantivo o pronome

Esempi:

- Ieri sera ho mangiato in un ristorante nuovo, il cibo era buonissimo, penso

ancora al piatto di pappardelle al ragù alla bolognese.

- Durante un viaggio in Italia, mia zia incontrò un ragazzo a Firenze, anche

dopo tutti questi anni, pensa ancora a lui.

- Sandro, hai uno sguardo lontano negli occhi, a chi stai pensando?

Pensare “di”

Il verbo pensare è seguito dalla preposizione “di” davanti a un verbo all’infinito.

Pensare + di + verbo

Esempi:

- Quel ristorante era così buono che la settimana prossima penso di ritornarci.

- Anche dopo tutto questo tempo, mia zia pensa di ritornare a Firenze.

- Sandro, pensi di telefonare alla persona a cui stai pensando?

??????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????

In Italian, the verb “to think” (pensare) can be followed by two different

prepositions: “a” or “di”.

Pensare “a”

We use the preposition “a” in front of a noun or a pronoun, to think about

someone or something. It can be used in the present, past, or future.

Examples:

- Yesterday evening I ate in a new restaurant, the food was very good, I still

think about the plate of pappardelle with its ragù alla Bolognese sauce.

- During a trip to Italy, my aunt met a young man in Florence, even after all

these years, she still thinks about him.

- Sandro, you have a faraway look in your eyes, who are you thinking about?

Pensare “di”

In Italian, we use the preposition “di” after “to think” in front of a verb in the

infinitive.

Examples:

- That restaurant was so good, that I’m thinking about returning next week.

- Even after all this time, my aunt still thinks about returning to Florence.

- Sandro, are you thinking about calling the person you are thinking about?

Saturday, January 27, 2024

|

|

BOTTONI

Sembra che la traduzione per “button” dall’inglese sia ovviamente “bottone”.

Hanno lo stesso suono dopo tutto. Ma come succede spesso, non è sempre così

semplice. In parte dipende dall’uso.

- Bottone:

Vanna ha comprato un nuovo cappotto di Armani con i bottoni d’oro.

- Pulsante:

Corrado ha premuto il pulsante sbagliato, e ha fatto saltare la corrente.

- Tasto: