Saturday, December 27, 2014

AUGURO A TUTTI UN

I WISH YOU ALL A

Saturday, December 20, 2014

SCHERZO, BATTUTA, BARZELLETTAQueste tre parole si traducono in inglese con la stessa parola: “joke” ma

hanno significati diversi: Consideriamo questi esempi.SCHERZO:

· Non è uno scherzo, lo dico sul serio.

· Luca ha fatto uno scherzo al suo maestro, ed è finito nell’ufficio della

preside.

BATTUTA:

· Il comico faceva una battuta dopo l’altra, ma gli spettatori non

ridevano.

· Ogni tanto ci vuole una bella battuta per cambiare l’aria.

BARZELLETTA:

· Luigi ha raccontato una barzelletta su un italiano, un francese, un

tedesco e un americano, finalmente mi ha fatto ridere.

· Non mi piacciono le barzellette sporche che racconta Gianrico.

E per le prossime settimane il mio blog andrà in vacanza. Lo dico sul serio,non

scherzo mica!*******************************************************************

SCHERZO, BATTUTA, BARZELLETTA

These three words all translate into English as “joke” however they have different

meanings. Let’s consider these examples:SCHERZO:

· It’s not a joke, I’m serious.

· Luca played a joke on his teacher and ended up in the principal’s office.

BATTUTA:

· The comic told one joke after the other but the spectators didn’t laugh.

· Every once in a while a joke is needed to change the mood.

BARZELLETTA:

· Luigi told a joke about an Italian, a Frenchman, a German and an American,

he finally made me laugh.

· I don’t like the dirty jokes that Gianrico tells.

And for the next few weeks my blog is going on vacation. I’m serious, I’m

not joking!

Saturday, December 13, 2014

MOLTO, TANTO, TROPPO o POCO

Sono variabili o invariabili? Sono aggettivi, avverbi o pronomi? La risposta è:

possono essere tutti e tre. Se la parola è usata per descrivere un sostantivo o

un pronome è un aggettivo, perciò è variabile. Se sostituisce un sostantivo, è

un pronome, ed è variabile. Se modifica un aggettivo o un verbo è un avverbio,

in questo caso è invariabile.* Guardiamo a degli esempi.MOLTO:

· I bambini avevano molta fame, hanno mangiato tutta la loro cena.

(aggettivo)

· Abbiamo viaggiato molto l’anno scorso, quest’anno abbiamo deciso di

rimanere a casa. (avverbio)

· La professoressa ha insegnato parecchi corsi, ma ce ne sono ancora molti

che lei vorrebbe insegnare prima di andare in pensione. (pronome)

TANTO:

· Oggi fa tanto freddo, mettiti il cappotto e i guanti! (aggettivo)

· Barbara ha parlato tanto al telefono, infatti, ha perso la voce. (avverbio)

· Avevo invitato solo cinque amici a cena, invece ce ne sono venuti tanti di

più.(pronome)

TROPPO:

· Loretta ha bevuto troppo vino ieri sera e oggi soffre di mal ditesta.

(aggettivo)· Sergio fuma troppo, e ora che smetta. (avverbio)

· In quella libreria ci sono molti libri strani, infatti, secondo me ce ne sono

troppi che trattano dei morti viventi. (pronome)

POCO:

· Ci sono poche camere libere in quell’albergo. (aggettivo)

· Claudio ha mangiato poco, vuole dimagrire prima della festa. (avverbio)

· Ho molti amici ma sfortunatamente pochi abitano in questa città,

(proverbio)

**************************************************************

MOLTO, TANTO, TROPPO o POCO

Are they variable or invariable? Are they adjectives, adverbs or pronouns?

The answer is: they can be all three. If the word is used to describe a

noun or a pronoun it is an adjective, therefore it is variable. If it

substitutes a noun, it’s a pronoun, and it’s variable. If it modifies an

adjective or a verb it’s an adverb, in this case it’s invariable.* Let’s look

at a few examples:MOLTO:

· The children were very hungry, they ate all their supper.

· We traveled a lot last year, this year we decided to stay home.

· The professor taught many courses, there are still many she would like to

teach before she retires.

TANTO:

· Today, it is very cold, put on your coat and your gloves.

· Barbara spoke a lot on the phone; in fact she lost her voice.

· I had invited only five friends to dinner, instead many more came.

TROPPO:

· Loretta drank too much wine last night and today she has a headache.

· Sergio smokes too much, it’s time he quit.

· In that bookstore there are many odd books, in fact, in my opinion there

are too many that deal with zombies.

POCO:

· There are few free rooms in that hotel.

· Claudio ate little; he wants to lose weight before the party.

· I have many friends, unfortunately only a few live in this city.

* Vi prego di notare che i significati variano in inglese.

* Please note that the meanings vary in English.

Saturday, December 6, 2014

BRAVO O BUONO O BELLO?

Queste tre parole spesso confondono gli studenti americani perché se

Così vale la pena ripassarne l’uso.

guardano nel loro dizionario per la traduzione di “good” trovano almeno queste

possibilità.

Bravo quando è usato da aggettivo, descrive esseri viventi: persone o animali,

le loro qualità, abilità, il loro valore. Non è usato per descrivere cose

inanimate.

Gemma è una brava cuoca.

- Fido è un bravo cane.

- Alessandra e Diana sono brave studentesse.

- Cristoforo e Giacomo sono bravi pasticceri.

Buono quando è usato da aggettivo, esprime un giudizio, descrive una qualità:

Abbiamo mangiato dei buoni biscotti e bevuto del buon caffè per colazione.

- Cristina è proprio una buon’amica.

- Hanno fatto un buon affare quando hanno comprato quella casa in città.

- Questo sciroppo è buono per la tosse.

Bello è un aggettivo che descrive un aspetto estetico di un sostantivo o

esprime un giudizio positivo. Ricordiamoci che qui stiamo parlando della

traduzione a “good” in inglese, non a “beautiful”.

- Ieri ho visto un bel film.

- Leggiamo delle belle novelle di Luigi Pirandello in classe.

E della parola bene? Ne parleremo un’altra volta.

_________________________________________________________________

These three words often confuse American students because if they look up

the translation for “good” in their dictionaries they will find at least these

possibilities: bravo, buono, or bello. Therefore, it’s a good idea to review their

uses.Bravo when it is used as an adjective describes living things: persons or

animals. It is not used to describe inanimate objects.Gemma is a good cook.

- Fido is a good dog.

- Alessandra and Diana are good students.

- Cristoforo and Giacomo are good bakers.

Buono when it is used as an adjective expresses a judgment or describes a

quality.

- We ate good cookies and drank good coffee for breakfast.

- Cristina is really a good friend.

- They made a good deal when the bought that house in town.

- This cough syrup is really good (for coughs).

Bello is an adjective that describes an esthetic aspect of a noun or expresses

a positive judgment. Remember that we are referring to the translation of

“good” from the English, not “beautiful”.

- Yesterday I saw a good movie.

- We are reading some good short stories by Luigi Pirandello in class.

What about the word bene? We’ll discuss it another time.

Saturday, November 29, 2014

I'm Late, I'm Late

for a very important date,

No time to say hello, goodbye,

I'm late, I'm late, I'm late.[From: the Walt Disney Productions animated movie "Alice in Wonderland"

(1951) Music by Sammy Fain / Lyrics by Bob Hilliard—Dal film d’animazione di

Walt Disney “Alice nel paese delle meraviglie” (1951), musica di Sammy Fain /

parole di BobHilliard]Se voglio esprimere l’idea di “late” in inglese che parola posso usare in

italiano? Ci sono due modi principali. Questa settimana esaminiamo

RITARDO:

ritardo delay/lateness/tardiness

Ci sono altre espressioni composte con questa parola:

arrivo in ritardo late arrival di ritardo behind time essere in ritardo to be late in ritardo late/delayed portare un ritardo di to run late/behind schedule senza (ulteriore) ritardo without (further) delay Nonostante tutte le espressioni a nostra disposizione, non possiamo

tradurre e rendere giustizia al testo della canzone del Coniglio

Bianco (o Bianconiglio) nelfilm di Walt Disney “Alice nel paese delle meraviglie”:Sono in ritardo, sono in ritardo,

per un appuntamento molto importante,

non ho tempo di dire salve, arrivederci,

sono in ritardo, sono in ritardo, sono in ritardo.Saturday, November 22, 2014

I'm Late, I'm Late

for a very important date,

No time to say hello, goodbye,

I'm late, I'm late, I'm late[From: the Walt Disney Productions animated movie "Alice in Wonderland" (1951)

Music by Sammy Fain / Lyrics by Bob Hilliard—Dal film d’animazione di Walt Disney

“Alice nel paese delle meraviglie” (1951), musica di Sammy Fain / parole di Bob

Hilliard]Se voglio esprimere l’idea di “late” in inglese che parola posso usare in italiano?

Ci sono due modi principali. Questa settimana esaminiamo TARDI:

è tardi it’s late Ci sono altre espressioni composte con questa parola:

al più tardi at the latest dormire fino a tardi to sleep in/sleep late fare tardi to be/run late meglio tardi che mai better late than never non è mai troppo tardi it’s never too late non più tardi di no later than più tardi later presto o tardi sooner or later si fa tardi/si sta facendo tardi it’s getting late sul tardi late/later in the day troppo tardi too late Per ora vi lascio perché, ieri ho fatto tardi, non ho potuto dormire fino a tardi

questa mattina; si sta facendo tardi e vorrei postare quest’articolo prima che si

faccia troppo tardi. A più tardi cari amici.Saturday, November 15, 2014

parte seconda

Come vi ho spiegato nella parte prima di questo blog, l’articolo che segue

viene dal sito web (www.confettidisulmona.net) della bellissima e

antichissima città di Sulmona situata nelle montagne dell’Abruzzo, la

quale produce i migliori confetti del mondo.Le origini della bomboniera

Il nome bomboniera deriva dal francese “bon-bon” (dolcetto) e il suo uso nasce

in Italia alla fine del 1400. Infatti, i nobili per contenere dolci e caramelle a base

di zucchero, sostanza importata dalle Indie e molto costosa a quel tempo,

utilizzavano dei cofanetti.Nel 1896 grazie alle nozze del principe di Napoli e futuro Re d’Italia, Vittorio

Emanuele III con Elena del Montenegro, la bomboniera diventa il regalo degli

sposi agli invitati facendo nascere così la tradizione che noi oggi tutti

conosciamo.La bomboniera cioè diventa l’oggetto con il quale si ricorda il giorno del

matrimonio e si ringraziano gli invitati per il dono ricevuto.

Come si preparano i confetti?

Le mandorle, opportunamente lavorate, sono messe in recipienti rotanti

chiamati “bassine“. Si distinguono per forma (a pera, a tamburo) o per il

tipo di rotazione (su asse obliquo, orizzontali con fondo forato, ecc.). Al loro

interno sono nebulizzate delle soluzioni di saccarosio che, grazie al

riscaldamento ottenuto per insufflazione di aria calda, evaporano lasciando uno

strato uniforme di zucchero sulla mandorla. Il processo prevede fasi ripetute di

bagnatura e di essiccamento, fino a ottenere lo strato di copertura voluto.La caratteristica dei confetti di Sulmona è che non prevedono l’uso di addensanti

(amido e farine). Hanno quindi esclusivamente una copertura di zucchero che li

rende particolarmente dolci e gustosi.Dopo la fase di rivestimento, i confetti presentano una superficie rugosa e

irregolare per cui subiscono la lisciatura, la colorazione (se necessaria) e la

lucidatura. La confettatura è un processo molto laborioso e può richiedere anche

due o tre giorni per essere completata.____________________________________________________________

part 2

As I explained in part one of this blog, the following article comes from the web

site (www.confettidisulmona.net) of the ancient and very beautiful city of Sulmona,

situated in the mountains of Abruzzo, which produces the best confetti in the

world.The origins of the “bomboniera” (party favor that holds the confetti)

The word “bomboniera” derives from the French bonbon (sweet) and its use begins

in Italy at the end of the 1400’s. In fact, the nobility used small chests to hold

sweets and candy made from sugar, a substance imported from the Indies which

was very expensive at that time.In 1896, thanks to the wedding of the Prince of Naples and the future King of Italy

Victor Emmanuel III to Elena of Montenegro, the bomboniera was the gift given to

the guests by the bride and groom, and thus began the tradition that we all know

today.The bomboniera is the object to remember the wedding day and to thank the

guests for their gift.How are confetti manufactured?

Almonds, properly worked, are placed in rotating containers called “bassine”.

They vary according to their shape (like a pear or a drum) or type of rotation (on a

slanting axis, horizontal with a perforated bottom, etc.). Inside these containers,

solutions of sucrose are atomized, thanks to increased temperature obtained by

blasts of hot air which when they evaporate leave a uniform layer of sugar on the

almond. The process repeats the phases of wetting and drying, until the desired

thickness is reached.A characteristic of the confetti from Sulmona is that they don’t use thickeners

(starch and flour). Therefore they only have a coating of sugar which makes them

particularly sweet and tasty.After the coating phase, the surface is rough and irregular leading to smoothing,

coloring (if necessary) and polishing. The production is a laborious process and

may take two to three days to complete.Saturday, November 8, 2014

Siccome mia nipote Carolina si sposa oggi, ho deciso di parlare di una

tradizione italiana, quella dei confetti. La bellissima e antichissima

città di Sulmona situata nelle montagne dell’Abruzzo produce i migliori

confetti del mondo. Mi sono rivolta al loro sito web

(www.confettidisulmona.net) per quest’articolo che ho copiato qui, in

parte. Un avvertimento: l’articolo è lungo, perciò l’ho diviso in due, la

seconda puntata andrà in onda la settimana prossima.LA STORIA DEL CONFETTO

Le origini del confetto sono antichissime. Secondo alcuni che si

avvalgono delle testimonianze delle Famiglie Fazi (447 a.C.) e di Apicio

(14-37 d.C.) amico dell’imperatore Tiberio, i confetti esistevano già in

epoca romana, tant’è che i Romani avevano l’usanza di festeggiare con il

confetto le nascite e i matrimoni ma, allora, era una specie di “bon-bon”

realizzato con anime di mandorle, miele e farina.La fabbricazione del confetto intesa in senso moderno però, avvenne

solo dopo la scoperta delle Indie Occidentali, quando lo zucchero

divenne il protagonista nella dolcificazione.Durante il periodo rinascimentale gli ospiti erano accolti con coppe

ricolme di confetti durante i ricevimenti per festeggiare i voti di

monache e sacerdoti.In letteratura sono molte le tracce lasciate sul confetto: dalle opere del

Boccaccio a quelle del Manzoni e di Goethe che regalò alla sua futura

moglie, uno scrigno colmo di confetti.Sempre nel ‘400, iniziò a Sulmona la fabbricazione dei confetti secondo

il criterio odierno. Nell’archivio del Comune si trovano alcuni documenti

datati 1492-1493 che lo testimonia. E sempre a Sulmona nel XV secolo

nasce la lavorazione artistica dei confetti presso il Monastero di Santa

Chiara. Con l’utilizzo di fili di seta i confetti erano legati per preparare

fiori, grappoli, spighe, rosari.Negli ultimi anni Sulmona si è affermata come patria indiscussa del

confetto. Grazie alla bontà del confetto ha saputo conquistare nel

tempo i mercati di tutto il mondo.Curiosità

I confetti nei secoli passati erano considerati bon-bon pregiati e quindi

riservati alle cerimonie importanti come le nozze di alto rango.I confetti simboleggiano l’unione della coppia attraverso le due metà

della mandorla, tenute insieme da uno strato di zucchero.Oggigiorno i confetti sono distribuiti, già confezionati in sacchetti, ma la

tradizione vuole che sia la sposa accompagnata dallo sposo al termine

del ricevimento, a distribuire con un cucchiaio d’argento i confetti sciolti

(e rigorosamente bianchi) disposti su un vassoio elegante e d’argento o

in un cesto; l’importante è che siano di numero dispari, generalmente il

numero di confetti presenti è 5 ma non è una regola. Anche il numero

comunque ha un significato:5 confetti rappresentano: fertilità, lunga vite, salute, ricchezza e felicità;

3 confetti simboleggiano: la coppia e il figlio;

1 confetto si riferisce invece, all’unicità dell’evento.

____________________________________________________________

My niece Carolyn is getting married today, so I decided to write about

an Italian tradition, that of confetti. The ancient and very beautiful city

of Sulmona, situated in the mountains of Abruzzo, produces the best

confetti in the world. I went to their web site

(www.confettidisulmona.net) for this article which I have reproduced

here in part. A note: the article is long, so I divided it in two; the

second installment will air next week.THE HISTORY OF CONFETTI

The origins of confetti are ancient. According to some--they refer to the

statements made by the Fazi Family (447 BCE) and to Apicio

(14-37 A.D.) friend of the Emperor Tiberius--confetti existed already in

Roman times. The Romans used confetti to celebrate births and

marriages, however at that time it was a type of bonbon made from

flour and honey with an almond in the center.The production of confetti as seen today, took place only after the

discovery of the West Indies, when sugar became the main sweetening

ingredient.During the Renaissance, guests were greeted with goblets filled with

confetti during receptions celebrating the vows taken by nuns and

priests.In literature we find many traces of confetti: from the works of

Boccaccio to those of Manzoni and Goethe, who gave his wife-to-be a

chest filled with confetti.The production method for confetti which is still used today in Sulmona

began in the 1400’s. The City archives contain several documents dated

1492-1493 which substantiate these facts. During the 15th century in

Sulmona the artistic production of confetti began at the Monastery of

Saint Chiara. Through the use of silk threads, confetti were tied

together into the shape of flowers, bunches of grapes, wheat, rosaries.Through the years, Sulmona has become the undisputed home of

confetti. Thanks to the goodness of the confetti, it has conquered

markets throughout the world.Did you know…

In the past, confetti were considered prized bonbons and therefore

reserved for important ceremonies such as weddings of high-rank.Confetti symbolize the union of the couple through the two halves of the

almond held together by a layer of sugar.Today confetti are distributed pre-packaged in bags, but tradition

states that it is the bride accompanied by the groom, who at the end of

the reception, distributes loose confetti (absolutely white) with a silver

spoon from an elegant silver tray or a basket; it is important

that the number be uneven, usually the number is 5, but it is not a

requirement. Even the number has a meaning:5 confetti represent: fertility, long life, health, wealth, and happiness;

3 confetti symbolize: the couple and a child;

1 confetto refers to the oneness of the event.

Saturday, November 1, 2014

VERBI IMPERSONALI

IMPERSONAL VERBS

I verbi impersonali sono quelli che non hanno un soggetto personale,

specifico.

Impersonal verbs are those that do not have a personal,

specific subject.

La maggior parte delle espressioni che descrivono il tempo o il clima o

l’orario sono impersonali; per esempio:

Most of the expressions that describe weather or climate or time of day are

impersonal; for example:

fa freddo it’s cold fa caldo it’s hot fa bello it’s nice/fair/fine fa brutto it’s bad/awful fa giorno it’s day fa notte it’s night è nuvoloso it’s cloudy è umido it’s damp c’è il sole it’s sunny c’è la nebbia it’s foggy piove it’s raining grandina it’s hailing nevica it’s snowing tuona it’s thundering tira vento it’s windy È l’una it’s one o’clock sono le tredici it’s one o’clock in the afternoon Altre comuni espressioni impersonali sono:

Other common impersonal expressions are:

c’è/ci sono there is/there are accade/avviene/succede (che) it happens (that) basta it’s enough/sufficient bisogna/occorre it is necessary (to) capita (che) it happens (that) conviene it makes sense, it’s a good idea importa it matters interessa it interests manca need/missing pare/sembra (che) it seems (that) si tratta di it’s a question of spetta/tocca it’s up to ci vuole it takes/requires

Saturday, October 25, 2014

ADDIO – ARRIVEDERCI -- CIAO -- SALVE

Ci sono vari modi di salutarsi in italiano ma quali sono le differenze?Addio è la forma di saluto usata per accomiatarsi definitivamente, sia

con persone sia con luoghi. [La parola è utilizzata con lo stesso

significato di arrivederci solo nell’italiano regionale toscano; fuori dalla

Toscana addio esprime congedo definitivo, mentre arrivederci

presuppone un nuovo incontro.]Arrivederci è l’espressione di saluto fra persone che si separano con la

certezza o speranza di rivedersi.Ciao è la forma di saluto amichevole usata al momento dell’incontro o

della separazione, ora di uso internazionale.Salve è una forma di saluto rivolta a una persona o a un luogo; può

avere tono solenne (in letteratura, poesia, o inni sacri) o tono

amichevole e confidenziale (tra persone). Era molto usata dagli antichi

romani sia per dare il benvenuto, sia per accomiatarsi. Oggigiorno io la

sento usata da commessi, una via di mezzo tra buon giorno e buona

sera (per dare il benvenuto in negozio) o ciao (troppo informale). Forse

è un ritorno alle nostre radici storiche e linguistiche?

GOODBYE

There are various ways to say goodbye in Italian, what are the

differences?Addio (literally “to God”) is the greeting used when a definitive

separation is expected, both with people and places. [The word is used

with the same meaning as arrivederci only in Tuscan regional Italian,

outside of Tuscany addio expresses a final goodbye, while arrivederci

presumes another meeting.]Arrivederci (literally “to/until we see each other again”) is the expression

used among persons who separate with the certainty or hope of meeting

up again.Ciao is the friendly greeting used at the time of meeting or separation,

it is now in use internationally.

Salve is used both with people and places; it may have a solemn tone

(in literature, poetry or sacred hymns) or a friendly tone

(between people). It was often used among ancient Romans both as a

greeting and a departure. Today I hear the word spoken by shop clerks,

a midpoint between good day and good evening (to welcome someone

into the store) or ciao (too informal). Perhaps it is a return to our

historic and linguistic roots?Saturday, October 18, 2014

TIZIO, CAIO E SEMPRONIO = TOM, DICK AND HARRYCi sono molti modi per esprimere CHIUNQUE in italiano:

Tal dei Tali

Signor Nessuno

Pinco Pallo

Pinco Pallino

o anche Mevio, Filano e Calpurnio,ma i nomi più comuni sono: Tizio, Caio e Sempronio.

Qual è l’origine di questo sodalizio? Gli studiosi ci dicono che

Anche se non sappiamo di certo a chi attribuire la nostra triade, è

compaiono per la prima volta riuniti nelle opere di Irnerio, giurista

medievale italiano e uno dei fondatori della Scuola di Diritto

dell’Università di Bologna. Irnerio (c. 1050—dopo il 1125) visse

durante il periodo della fondazione dell’Università più antica d’Europa

nel 1088, e fu il primo ad adoperare l'unione classica: Titius, Gaius et

Sempronius. Le origini dei nomi non sono chiare, alcune sono

attribuite alla famiglia Gracco: Tizio derivato da Tiberio Gracco; Caio

da Caio Gracco suo fratello, e Sempronio da Sempronio Gracco, il

loro padre. Ma abbiamo anche Tito Flavio Vespasiano e Tito Livio, o

la conoscenza che Gaio era un nome comunemente usato dagli

antichi romani.

molto più elegante degli equivalenti in inglese: Tom, Dick and Harry,

Average Joe, Ordinary Joe, John Doe, Joe Sixpack, Ordinary o

Average Jane, Jane Doe, Jane Smith, John Q. Public, Joe Blow, Joe

Schmoe, John Smith, Eddie Punchclock, Joe Botts, J. S. Ragman,

Vinnie Boombotz.............................................................................

There are many ways to say ANYBODY or ANYONE in Italian:So and So

Mr. Nobody

Pinco Pallo

Pinco Pallino

o even Mevio, Filano e Calpurnio.However the most common names are: Tizio, Caio e Sempronio.

What is the origin of this association? Scholars tell us that they

appear together for the first time in the works of Irnerio, a medieval

Italian jurist and one of the founders of the School of Law at the

University of Bologna. Irnerio (c. 1050—d. after 1125) lived during

the period of the establishment of the oldest university in Europe in

1088, and was the first to use this classic union: Titius, Gaius et

Sempronius. The origins of the names are not clear, some are

attributed to the Gracco family: Tizio derived from Tiberius Gracco,

Caio from Caio Gracco, his brother and Sempronio from Sempronio

Gracco, their father. Yet we also have Tito Flavio Vespasiano and

Tito Livio or the knowledge that Gaio was one of the names

commonly used in ancient Rome.Even if we don’t know for certain who we can attribute our triad to,

it is much more elegant than the English equivalents: Tom, Dick and

Harry, Average Joe, Ordinary Joe, John Doe, Joe Sixpack, Ordinary

or Average Jane, Jane Doe, Jane Smith, John Q. Public, Joe Blow,

or Average Jane, Jane DoeJane Doe, Jane Smith, John Q. Public, Joe Blow,

Joe Schmoe, John Smith, Eddie Punchclock, Joe Botts, J. S. Ragman,

Vinnie Boombotz.Saturday, October 11, 2014

DEI TEMI DEL MIO BLOG

da maggio a settembre 2014FALSI AMICI: 3 maggio 2014

I

YOU: 10 maggio

MAGARI 17maggio

VOLERCI: 24 maggio

METTERCI: 1° giugno

BOCCE: 7 giugno

FARE: 14 giugno

LA COPPA DEL MONDO/ The World Cup: 21 giugno

LE PARTI DEL DISCORSO/Parts of Speech: 28 giugno

LASCIARE = Leave?: 5 luglio

MA DAI!: 13 luglio

PAROLE INVARIABILI: 19 luglio

PAROLE CON DUE FORME AL PLURALE—PARTE I: 26 luglio

IN BOCCA AL LUPO!: 2 agosto

PLAY—COME SI TRADUCE IN ITALIANO? 9 agosto

FERRAGOSTO: 16 agosto

PAROLE CON DUE FORME AL PLURALE—PARTE I: 23 agosto

MENTRE O DURANTE: 30 agosto

L’ARMISTIZIO DELL’8 SETTEMBRE 1943: 6 settembre

L’ORIGINE DEI NOMI DELLA SETTIMANA: 13 settembre

MAMMONE: 20 settembre

STIPENDIO E SALARIO (PARTE I): 27 settembre

Saturday, October 4, 2014

SALARIO E STIPENDIO (Parte I)

L’altro ieri uno studente mi ha chiesto qual è la differenza tra: salario e

stipendio.SALARIO: di solito indica la remunerazione del lavoro manuale

dipendente operaio, perlopiù operaio o bracciante agricolo (i cosiddetti

colletti blu);STIPENDIO: indica la paga mensile, sempre del lavoro dipendente,

però di natura impiegatizia o funzionaria (i cosiddetti colletti bianchi).Il Vocabolario etimologico della lingua italiana di Ottorino Pianigiani

(1991 Edizioni Polaris) ci fornisce queste definizioni:Salàrio fr. salaire; ingl. Salary: --lat. SALARIUM dal lat. SAL sale /con la

desinenza-ARIUM indicante attinenza/ (cfr. Salara), perché i magistrati e

i soldati romani ricevevano per loro nutrimento grani, vino, olio e

particolarmente sale; donde <<salàrium>> venne il loro soldo chiamato.

Col tempo, tali somministrazioni si compensarono in danaro, ma

conservarono il nome antico. [p.1185]

MAMMONE

Se controlliamo in vari d

Stipèndio – lat. STIPÈNDIUM per STI-PI-PÈNDIUM da STIPS – genit.

STIPIS – pesante moneta di rame d’infima qualità, che pare debba

riferirsi alla rad. STA-, STAP- esser saldo, solido /ond’anche la voce

stipes tronco, ceppo/ (v. Stare e cfr. Stipite) e così formato nella medesi

ma relazione d’idee del ted. Stüber soldo (cfr. Soldo): o PÈNDERE

pesare, e /quando al metallo greggio venne dopo Servio Tullio sostituita

la moneta coniata/ pagare, sborsare.

Dapprima significò la Paga dei soldati, ed oggi la Provvisione che si

dà a persone di qualità. Deriv. Stipendiare. [p.1861]...................................................................

SALARY AND PAY (Part I)

The day before yesterday, a student asked me the difference between:

salary and stipend.SALARY: usually refers to the remuneration for the work of the

dependent manual workman, mainly a laborer or field hand (the so-called

blue collars);PAY/STIPEND: refers to the monthly pay, also for dependent work,

however of a clerical or functionary nature (the so-called white collars);The Etymological Dictionary of the Italian Language by Ottorino

Pianigiani (1991 Edizioni Polaris) provides us with these definitions:Salary: because the Roman magistrates and soldiers received their

provisions in grain, wine, oil and especially salt, their coin was later

called <<salàrium>>. This compensation was later paid in money, yet

still maintaining the ancient name. *Pay/Stipend: the word derives from a heavy copper coin of very poor

quality (Stipis) plus the Latin word to weigh. The term was used at the

pay given to soldiers and later to persons of quality. **Please note that the translations are not verbatim.

Saturday, September 27, 2014

izionari disponibile on-line—per esempio:

Treccani.it, Garzanti Linguistica, ecc.—la definizione della parola

“mammone” è più o meno la stessa. Io preferisco la definizione di:Il Sabatini Coletti Dizionario della Lingua Italiana

[mam-mó-ne] s.m. (f. -na)

- • fam. Bambino o adulto che è eccessivamente attaccato alla madre

- • Anche in funzione di agg.: un bambino m.

- • a. 1967

Questi giorni sto rileggendo il romanzo del grande scrittore siciliano

Leonardo Sciascia A ciascuno il suo [Adelphi Edizioni, 1988, pp. 46-47] e

ci ho trovato una spiegazione molto più completa e poetica:

<< Per la sua vita privata era considerato una vittima

dell’affetto esclusivo e geloso della madre: ed era vero. A quasi

quarant’anni ancora dentro di sé andava svolgendo vicende di desiderio

e d’amore con alunne e colleghe che non se ne accorgevano o se ne

accorgevano appena: e bastava che una ragazza o una collega

mostrasse di rispondere al suo vagheggiamento perché subito si

gelasse. Il pensiero della madre, di quel che avrebbe detto, del giudizio

che avrebbe dato sulla donna da lui scelta, della eventuale convivenza

delle due donne, della possibile decisione di una delle due di non fare

vita in comune, sempre interveniva a spegnere le effimere passioni, ad

allontanare le donne che ne erano state oggetto come dopo una triste

esperienza consumata e quindi con un senso di sollievo, di liberazione.

Forse ad occhi chiusi avrebbe sposato la donna che sua madre gli

avesse portato; ma per sua madre lui, ancora così ingenuo, così

sprovveduto, così scoperto alla malizia del mondo e dei tempi, non era

in età di fare un passo tanto pericoloso. >>...................................................................

If we consult various online dictionaries—for example: Treccani.it,

Garzanti Linguistica, etc.—the definition of the word “mammone” is

more or less the same. I prefer the definition in:Sabatini Coletti Dictionary of the Italian Language

- • fam. A child or adult who is excessively attached to his mother

- • Also used as an adjective: un bambino m.

- • a. 1967

These days I’m rereading the novel by the great Sicilian writer Leonardo

Sciascia A ciascuno il suo (To Each His Own) and in it I found a much

more complete and poetic explanation:”In his private life he was considered a victim of his mother’s

exclusive and jealous affection, and it was true. At nearly forty years of

age, within him unfolded incidents of desire and love towards students

and colleagues, who either took no notice at all or barely noticed. It

was enough for a young woman or a colleague to react to his pipe

dreams for him to immediately freeze up. Thoughts of his mother, of

what she would say, of the judgment she would pass on the woman he

had chosen, of the eventual living together of the two women, of the

possible decision of one of the two to not have a life in common, always

intervened to extinguish the ephemeral passions, to distance the women

who had been the object, like after a sad consummated experience, and

therefore with a sense of relief, of freedom. Perhaps with his eyes

closed he would have married the woman his mother would have brought

him; but for his mother he, still so naïve, so inexperienced, so exposed

to the malice of the world and the times, he was not of the age to take

such a dangerous step.”Saturday, September 20, 2014

LE ORIGINI DEI NOMI DEI GIORNI DELLA SETTIMANA:

La parola “settimana” deriva da quella latina “septimana” (che significa:

in numero di sette). I nomi dei giorni furono assegnati dai Babilonesi

verso il VI a.C. ed ereditati dai Romani verso il II secolo a. C.. Queste

parole traggono origine dai corpi celesti in movimento fra le stelle fisse

che erano in sostanza gli elementi del sistema solare visibili a occhio

nudo: il Sole, la Luna e i cinque pianeti noti fin dall'antichità: Marte,

Mercurio, Giove, Venere e Saturno.LUNEDÌ: dal latino Dies lunae o giorno della luna. È il primo giorno

della settimana nel calendario gregoriano e il primo della settimana

lavorativa.

MARTEDÌ: dal latino Martis dies o giorno di Marte.MERCOLEDÌ: dal latino Mercurii dies ossia giorno di Mercurio.

GIOVEDÌ: dal latino Jovis dies, vale a dire giorno di Giove.

VENERDÌ: dal latino Veneris dies che significa giorno di Venere.

SABATO: ha due radici, la prima dal latino Saturni dies, il giorno di

Saturno. Il nome pagano del giorno dedicato a Saturno fu sostituito da

“sabato” dal termine ebraico Shabbat o Sabbat, in altre parole il giorno

di riposo. L’inglese ha mantenuto le radici originali in “Saturday”.DOMENICA: Anche il settimo giorno della settimana ha due basi.

Originalmente era il giorno del Sole, nome che si ritrova tuttora

nell’inglese “Sunday” e nel tedesco “Sonntag”. Dopo è stato sostituito

con il nome di “domenica” provvidente dal latino Dies Dominicus, che

significa giorno del Dominus (Signore), dall'Imperatore romano

Costantino (c. 272-337 d.C.) il quale si era convertito al Cristianesimo.THE ORIGINS OF THE NAMES OF THE DAYS OF THE WEEK:

In Italian, the word “week” derives from the Latin “spetimana” (which

means: in the number seven). The names of the week were given by the

Babylonians around the VI century BCE and inherited by the Romans

around the II century BCE. These words find their origins in the celestial

bodies in movement among the fixed stars which were in essence the

elements of the solar system visible with the naked eye: the Sun, the

Moon, and the five planets known from ancient times as: Mars, Mercury,

Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn.LUNEDÌ: from the Latin Dies lunae, the day of the moon. It is the first

day of the week in the Gregorian calendar and the first day of the work

week in Italy.

MARTEDÌ: from the Latin Martis dies, the day of Mars.MERCOLEDÌ: from the Latin Mercurii dies, the day of Mercury.

GIOVEDÌ: from the Latin Jovis dies, the day of Jupiter.

VENERDÌ: from the Latin Veneris dies, the day of Venus.

SABATO: has two roots: the first from the Latin Saturni dies, the day of

Saturn. The pagan name of the day dedicated to Saturn was substituted

by “sabato” from the Jewish word Shabbat or Sabbat, in other words the

day of rest. English has maintained the original “Saturday”.DOMENICA: even the seventh day of the week has two bases.

Originally it was the day of the Sun as can be found in the English

“Sunday” and in the German “Sonntag”. Later it was substituted with the

name “Domenica” from the Latin Dies Dominicus meaning the day of

Dominus (God) by the Roman Emperor Constantine (c. 272-337) who

was converted to Christianity.Saturday, September 13, 2014

8 settembre 1943, l'armistizio

detto anche l’Armistizio corto, fu firmato il 3 settembre a Cassabile

in provincia di Siracusa.Segue il testo del proclama del Maresciallo Pietro Badoglio,

trasmesso alle 19:45 alla radio (EIAR: Ente italiano per le audizioni

radiofoniche).

"Il governo italiano, riconosciuta la impossibilità di continuare l’impari

lotta contro la soverchiante potenza avversaria, nell’intento di

risparmiare ulteriori e più gravi sciagure alla nazione, ha chiesto un

armistizio al generale Eisenhower, comandante in capo delle forze

alleate anglo-americane. La richiesta è stata accolta.

Conseguentemente ogni atto di ostilità contro le forze anglo-

americane deve cessare da parte delle forze italiane in ogni luogo.

Esse però reagiranno ad eventuali attacchi di qualsiasi altra

provenienza".Il giorno seguente i giornali pubblicarono titoli di prima pagina <<LA GUERRA È FINITA>>,

ma l’Italia entrò in un periodo bruttissimo della sua storia: la fuga della famiglia reale e di

Badoglio, la liberazione di Mussolini, la creazione della Repubblica di Salò, lo sbandamento

dell’esercito italiano, l’invasione tedesca, e la lista continua. In altre parole: l’Italia che si

era unita con così tanti sacrifici nel 1860, si trovava di nuovo un paese diviso, invasa da

truppe straniere, sanguinante.

..................................................................September 8, 1943, the Armistice,

also known as the Short Armistice,

was signed on September 3 at Cassablie

in the province of Syracuse (Sicily).What follows is the body of the proclamation by Marshal

PietroBadoglio which was broadcast at 7:45 p.m. on EIAR,

the Italian National Radio:“The Italian government, recognizing the impossibility of continuing

the unequal struggle against an overwhelming enemy force, in order

to avoid further and graver disasters for the Nation, sought an

armistice from General Eisenhower, commander-in-chief of the

Anglo-American Allied forces. The request was granted.

Consequently, all acts of hostility against the Anglo-American forces

by Italian forces must cease everywhere. They (the Italian forces)

will react to eventual attacks from any other source.”The following day the newspaper headlines read: <<THE WAR IS OVER>>, however Italy

was to enter a very ugly period of its history: the flight of the royal family and Badoglio,

the liberation of Mussolini, the creation of the Republic of Salò, the confusion within the

Italian army, the German invasion, and the list goes on. In other words: the Italy that

had united itself with so many sacrifices in 1860, finds itself again a divided nation,

invaded by enemy troops, and bleeding.Saturday, September 6, 2014

MENTRE o DURANTE?

All’inizio dei loro studi, a volte i miei studenti hanno difficoltà con la differenza tra

gli usi di MENTRE e DURANTE. Guardiamo alcuni esempi:

Mentre è una congiunzione usata per esprimere: “nel tempo in cui, intanto che”. È

seguita da un verbo:

Mentre parlavo Luigi mi guardava fisso.

Il furto è successo mentre eravamo fuori casa a fare la spesa.

Mentre Elena studia, le piace ascoltare la musica.

Il bis è successo mentre suonavate l’ultima ballata.

Durante è una preposizione usata per esprimere: “nel tempo in cui, intanto che”. È

seguita da un sostantivo:

Durante dicembre, trascorriamo le vacanze natalizie con la famiglia di mia sorella.

Si sono annoiati durante il film.

Sandro ha perso il posto durante la crisi economica.

Molte persone innocenti sono morte durante la guerra.

At the onset of their studies, at times my students have trouble with the difference

between the uses of “MENTRE” and “DURANTE”. Let’s look at a few examples:

Mentre is a conjunction used to express: “at the time which, while”. It is followed

by a verb:

While I was speaking Luigi looked at me intently.

The robbery happened while we were out of the house shopping.

While Elena, studies, she likes to listen to music.

The encore occurred while you played your last ballad.

Durante is a preposition used to express: “at the time which, during”.

It is followed by a noun:

During December we spend our Christmas vacation with my sister’s family.

They got bored during the movie.

Sandro lost his job during the economic crisis.

Many innocent people died during the war.

Saturday, August 30, 2014

NOMI CON DUE FORME DI PLURALE—SECONDA PARTEAlcuni nomi maschili in -o hanno due forme di plurale, una regolare in -i (maschile) e

l’altra in –a (femminile). Nella maggior parte dei casi i due plurali hanno un

significato diverso. Ecco degli esempi e il loro significato.

1. il fondamento:

i fondamenti: in senso figurato: i principi di base e di sostegno di una

disciplina accademica o una scienza;

le fondamenta: con valore concreto: la parte sotterranea di una costruzione,

di un palazzo2. il frutto:

i frutti: in senso generico, i risultati

le frutta: le cose che si mangiano, come le mele, le albicocche3. il gesto:

i gesti: movimenti o atteggiamenti del copro, delle mani, delle braccia;

le gesta: imprese o azioni ammirevoli, come di un eroe4. il grido:

i gridi: quegli degli animali

le grida: degli esseri umani5. il labbro:

i labbri: in senso figurato: i margini di una ferita; i bordi di un vaso, o degli

animali;

le labbra: della bocca umana6. il lenzuolo:

i lenzuoli: più di una ma solo quando sono considerati uno ad uno

le lenzuola: un paio che si usano sul letto7. il membro:

i membri: quelli che fanno parte di una famiglia, di una commissione, di

un’associazione, di un partito;

le membra: le parti del corpo, sia umano che animale8. il muro:

i muri: di una casa

le mura: di cinta di una città o di una fortezza9. l’osso:

gli ossi: le parti ossee di animali macellati;

le ossa: l’insieme dell’ossatura umana

NOUNS WITH TWO PLURAL FORMS—PART TWO

1. Foundation:

masculine plural: in the figurative sense, of a science or an academic

discipline

feminine plural: in the concrete sense: of a structure2. Fruit:

masculine plural: the results

feminine plural: what we eat, like apples or apricots3. Gesture:

masculine plural: movements of the body

feminine plural: heroic feats4. Shout:

masculine plural: of animals

feminine plural: of humans5. Lip:

masculine plural: in the figurative sense, the edge or the margins of a street

or ditch

feminine plural: of humans6. Sheet:

masculine plural: more than one when considered one at a time

feminine plural: a set of sheets when used to make up a bed7. Member:

masculine plural: of a family, a political party

feminine plural: of the body8. Wall:

masculine plural: of a house

feminine plural: of a city or fortress9. Bone:

masculine plural: of butchered animals

feminine plural: human skeletal systemSaturday, August 23, 2014

Ferragosto, che deriva dal latino feriae Augusti (riposo di Augusto), fu stabilito nel

18 a.C. dall’imperatore Ottaviano Augusto. Era un periodo di riposo e di

festeggiamenti che aveva origini nelle tradizioni della Vinalia rustica o Consualia,

feste che celebravano la raccolta dopo la fine dei duri lavori agricoli; erano dedicate

a Conso, dio della terra e della fertilità.In tutto l’Impero si organizzavano feste e corse di cavalli, e gli animali da tiro,

liberati dai lavori nei campi, erano adornati di fiori. Infatti, il palio di Siena che è

celebrato il 16 agosto ha le sue radici in queste feste antiche. La parola “palio”

deriva dal latino pallium, una tela preziosa che era il premio dato ai vincitori delle

corse di cavalli. Inoltre, in questi giorni, i contadini facevano gli auguri ai

proprietari dei terreni, ricevendo in cambio una mancia.Oggi è tutt’altra cosa!

Ferragosto, based on the Latin Feriae Augusti (Augustus' rest), was established in

the year 18 BC by the emperor Augustus. It was a period of rest and festivity that

had its origins in Vinalia rustica or the Consualia, which celebrated the harvest after

the end of a long period of intense agricultural labor. The celebrations were

dedicated to Conso, the god of the earth and fertility.Throughout the Empire horse races were organized, and beasts of burden, freed

from their labors in the fields, were adorned with flowers. In fact, the Palio of

Siena which is celebrated on August 16th has its roots in these ancient festivals.

The word “palio” derives from the Latin pallium, a precious cloth which was the

usual prize given to winners of the horse races. Also, during this time, the farmers

greeted the landowners who in return would give them a tip.Today things are totally different!

Nel frattempo ……… Meanwhile……….

Saturday, August 16, 2014

Quando uno studente cerca nel vocabolario per la traduzione della parola “play”,

s’imbatte in una lunghissima lista di significati divisi tra sostantivi e verbi.

Esaminiamone alcuni!Iniziamo con i verbi:

I bambini giocano a calcio nel campetto qui vicino. (giocare)

A me piace giocare a bridge, ma tu preferisci gli scacchi. (giocare)

Il violinista suona un violino rarissimo. (suonare)

Piacerebbe partecipare anche a Giacomo. (partecipare)

Anna Magnani ha recitato la parte di Pina in quale film? (recitare)

Rappresentano “Sei personaggi in cerca d’autore” di Luigi Pirandello al Teatro

Centrale. (rappresentare)Finalmente sono riuscito ad avere un ruolo in quel nuovo film che stanno girando a

Cinecittà. (avere)Sto facendo vedere il nuovo DVD ai miei amici. (far vedere)

Ti faccio ascoltare il nuovo concerto sinfonico. (far ascoltare)

E adesso alcuni sostantivi:

Ieri sera abbiamo visto uno spettacolo eccellente a teatro.

Non prendertela, era soltanto un gioco di parole.

Tocca a me è il mio turno.

Il furto del capolavoro dal museo ha avuto molta attenzione nei giornali.

Ho guardato i riflessi dei raggi di luna sul laghetto.

When a student looks up the translation for the word “play” in the dictionary she

encounters a long list of meaning divided into nouns and verbs. Let’s look at some

of them!Let’s begin with the verbs:

The children play soccer in the little field nearby.

I like to play bridge, but you prefer chess.

The violinist plays a very rare violin.

Even Giacomo would like to play.

Anna Magnani played the role of Pina in which film?

They are playing “Six Characters in Search of an Author” by Luigi Pirandello at the

Central Theatre.I was finally able to play a role in that new movie they are filming at Cinecittà.

I am playing the new DVD for my friends.

I will play the new concert for you.

And now some nouns:

Yesterday evening we saw an excellent play at the theatre.

Don’t get upset, it was just a play on words.

It’s my turn, it’s my play.

The theft of the masterpiece from the museum received a lot of play in the

newspapers.I watched the play of the moonbeams on the lake.

Saturday, August 9, 2014

IN BOCCA AL LUPO….CREPI (IL LUPO)!

Che c’entra il lupo con la fortuna? E perché deve morire? Quali sono le origini di

questa espressione strana di buon augurio?L’Accademia della Crusca* ci dice che le origini sono antichissime e probabilmente

risalgono a una forma di augurio rivolta ai cacciatori, i quali si dovevano avvicinare

al lupo per poterlo ammazzare. Anche la risposta rivela la credenza nel potere

magico di impedire la mala sorte attraverso le parole. Esistono anche molti

riferimenti letterari al potere del lupo, pensiamo alle fiabe di Esopo o ai Fioretti di

San Francesco.Altre interpretazioni popolari alludono alla legenda di Romolo e Remo salvati dalla

lupa, ma poi la risposta non ha senso, se fosse morta la lupa, i due gemelli non

sarebbero sopravvissuti.C’è anche il richiamo marinesco. A Venezia, quando i capitani delle navi ritornavano

da viaggi, registravano su una specie di lavagna chiamata “la bocca di lupo” i beni

accumulati durante il viaggio e gli uomini che erano ritornati. Perciò era un augurio

di buona fortuna, l’essere registrato sulla lavagna del lupo.Anche se le origini di quest’augurio non sono chiare, la cosa importante da ricordare

è: la risposta è “crepi”, non rispondere “grazie”, chissà dove finirete, forse nello

stomaco del lupo.IN THE MOUTH OF THE WOLF…(MAY THE WOLF) DIE!

What does the wolf have to do with luck? And why does he have to die? What are

the origins of this strange expression of good luck?The Accademia della Crusca* tells us that the origins are ancient and probably date

back to a form of address to hunters, who had to get very close to the wolf in order

to kill it. Even the answer reveals the belief in the magical power that words had to

stop bad luck. There are many literary references to the power of the wolf, think

about Aesop’s fables or the poems of Saint Francis of Assisi.Other popular interpretations refer to the legend of Romulus and Remus who were

saved by the she wolf, however the answer doesn’t make sense, because if the she

wolf had died, the twins would not have survived.There is even a maritime reference. In Venice, when the ship captains returned

from their voyages, they recorded, on a type of blackboard called “the mouth of the

wolf”, the survivors of the trip and the goods they had accumulated. Therefore it

was a wish of good fortune to be registered on the wolf’s blackboard.Even if the origins of this greeting or wish are not clear, the important thing to

remember is to answer “die”, do not say “thank you”, who knows where you’ll end

up, perhaps in the stomach of the wolf.*Accademia nata a Firenze nel 1582 è destinata allo studio e alla conservazione

della lingua nazionale italiana. // Academy founded in Florence in 1582, it is

dedicated to the study and conservation of the Italian national language.Saturday, August 2, 2014

NOMI CON DUE FORME DI PLURALE—PRIMA PARTE

Alcuni nomi maschili in -o hanno due forme di plurale, una regolare in -i (maschile)

e l’altra in –a (femminile). Nella maggior parte dei casi i due plurali hanno un

significato diverso. Ecco degli esempi e il loro significato.

1. il braccio:

i bracci: di una struttura meccanica, per esempio: della croce; della lampada,

della bilancia, di un fiume, di un candelabro;

le braccia: del corpo umano2. il budello:

i budelli: tubi, cose lunghe e strette, anche in senso metaforico, vie, strade;

le budella: gli intestini3. il calcagno:

i calcagni: in senso concreto, parte posteriore dei piedi, delle calze, delle

scarpe;

le calcagna: solo in senso figurato: stare alle calcagna di qualcuno, avere

qualcuno alle calcagna: essere inseguito4. il cervello:

i cervelli: nel senso di persone dotate di ingegno: le menti, le intelligenze, gli

ingegni

le cervella: materia cerebrale di uomini e animali5. il ciglio:

i cigli: in senso figurato, per esempio: i margini, gli orli o i bordi di una strada

o di un fosso;

le ciglia: degli occhi6. il corno:

i corni: strumenti musicali

le corna: degli animali7. il dito:

i diti: considerati distintamente, con valore specifico: i diti pollici, medi,

anulari, ecc.;

le dita: considerate in senso collettivo, della mano, dei piedi8. il filo:

i fili: con significato concreto: i fili elettrici, d’erba, di seta;

le fila: in senso figurato: le fila di un discorso, di un racconto;

nell’espressione "tenere le fila di qualcosa" che significa "dirigere, gestire qualcosa"

o "tirare le fila di qualcosa" che significa "cercare di concludere qualcosa"Non cambiare canale, ritornerò con la parte seconda!

Friday, July 25, 2014

PAROLE INVARIABILI: quelle che non cambiano WORDS THAT DON’T CHANGE: fromdal singolare al plurale sono di vario genere: singular to plural fall into various categories:

- Nomi che terminano con la vocale accentata: 1. Words that end with an accented vowel:

la beltà-le beltà beauty-beauties

il caffè-i caffè coffee-coffees

la città-le città city-cities

il paltò -i paltò overcoat-overcoats

il pascià-i pascià pasha-pashas

l’università-le università university-universities

la virtù-le virtù virtue-virtues

[Da questo punto in poi lascio a voi il compito [From this point forward, I will leave the task

di pluralizzare—buon divertimento!] of pluralizing up to you—have fun!]

- Nomi che terminano in consonante: 2. Words that end with a consonant:

l’autobus bus

il bar bar

il pantheon pantheon

il parquet wood floor

lo sport sport

il tram tram

il würstel hot dog/Vienna sausage

- Nomi e aggettivi monosillabici: 3. Monosyllabic nouns and adjectives:

blu blue

il dì day

lo gnu gnu

il re king

il sì yes

il tè tea

- Nomi che terminano in "i": 4. Words that end with the letter “i”:

l’alibi alibi

l’analisi analysis

la crisi crisis

la parentesi parenthasis/bracket

la sintesi synthesis

la tesi thesis

- Nomi abbreviati: 5. Shortened words:

l’auto automobile

la bici bike

il cinema cinema

la moto motorcycle

la radio radio

lo stereo stereo

- Parole straniere: 6. Foreign words:

il drive

il mouse

la paella I’ll leave these translations up to you!

il party

la performance

il software

- Nomi composti di un verbo e un sostantivo: 7. Combination of a verb and a noun:

l’asciugacapelli hair dryer

il cavatappi corkscrew

il passamontagna balaclava

il/la portalettere mail carrier

lo scioglilingua tongue-twister

il tritacarne meat grinder

Saturday, July 19, 2014

Ma dai…

È una di quelle espressioni usate di continuo e può esprimere:

Approvazione:

Giacomo: “Ho finalmente finito la tesi.”

Vanna: “Ma dai…complimenti!”

Incoraggiamento:

“Ma dai, assaggia gli spinaci, vedrai che ti piaceranno.”

Fastidio:

“Ma dai, smettila di gironzolarmi intorno!”

Sorpresa:

Gemma: “Ho smesso di fumare.”

Caterina: “Ma dai!”

Irritazione:

“Ma dai Giorgio, ti ho capito la prima volta, basta così, non devi continuare a

ripetere le stesse cose!”

Esasperazione:

“Ma dai…come fai a non capire, te l’ho spiegato almeno dieci volte!”

Incredulità:

Cristina: “Ieri ho vinto la lotteria, e domani mi comprerò quella Ferrari che ho

sempre desiderato.”Teresa: “Ma dai?”

It is one of those terms that is used all the time and can express:

Approval:

Giacomo: “I finally finished by thesis.”

Vanna: “Wow…congratulations!”

Encouragement:

“Come on, taste the spinach, you’ll see you’ll like them.”

Annoyance:

“Come on, stop hanging around me!”

Surprise:

Gemma: “I quit smoking.”

Catherine: “Come on, I’ll be…”

Irritation:

“Okay George, I understood you the first time, that’s enough, you don’t have to

repeat the same things over again.”

Exasperation:

“Come on, how is it you don’t understand, I explained it at least ten times.”

Incredulity:

Christine: “Yesterday I won the lottery, and tomorrow I will buy that Ferrari that I

always wanted.”Teresa: “Oh really?”

Saturday, July 12, 2014

A volte dobbiamo tradurre una parola che appare semplice e ci troviamo a tu per tu

con una lunga scelta. Prendiamo il verbo “TO LEAVE” per esempio.Può essere tradotto come:

- LASCIARE:

Vorrei lasciare tutto di spiacevole alle mie spalle.- PARTIRE:

Gianni è partito da Roma in treno questo pomeriggio.- DIMENTICARE:

“Che sbadato, ho dimenticato il portafoglio a casa!”- USCIRE DA:

Appena che è entrata la padrona di casa, il ladro è uscito dalla finestra.- ANDARE VIA:

“Sto cercando la Professoressa Campoli.” “Mi dispiace, ma è già andata via.”- RIMANERE:

Abbiamo speso €85 oggi, così ce ne rimangono soltanto €15 dai €100 che abbi

amo prevalso dal bancomat.- FARE:

Mariuccia ha solo quattro anni, ma è brava a scuola, sa che 7 meno 2 fa 5.E per ora vi saluto e vi lascio, alla prossima settimana.

- I would like to leave all the unpleasantness behind.

- Gianni departed Rome this afternoon by train.

- “How absent-minded I am, I left my wallet at home.”

- As soon as the owner entered, the thief left through the window.

- “I’m looking for Professor Campoli.” “I’m sorry, she has already left.”

- Today we spent €85, therefore we only have €15 left from the €100 we

withdrew from the ATM.- Mariuccia is only four years old, but she does well at school, she knows that 7

minus 2 leaves 5.

And for now, I will say goodbye and leave you, until next week.

Saturday, July 5, 2014

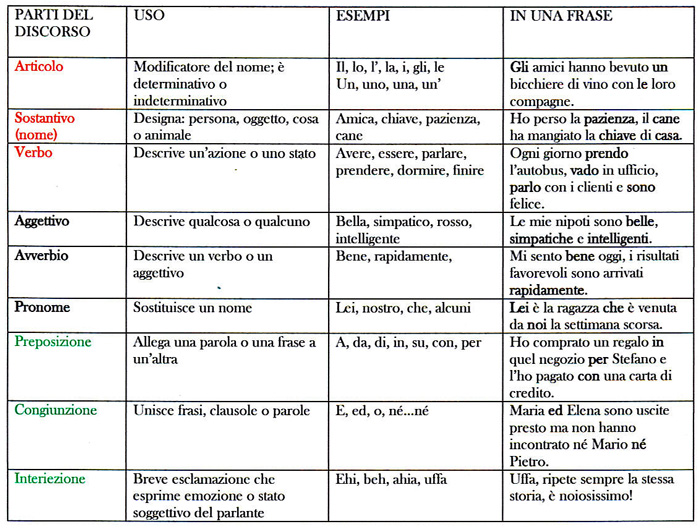

LE PARTI DEL DISCORSO

Lo studente entra in una classe d’italiano per la prima volta ed è immediatamente

assalito da concetti che o non ha mai studiato o ha dimenticato molti anni fa: le

parti del discorso.Sono divise in nove categorie, ripassiamole:

THE PARTS OF SPEECH

The student enters an Italian class for the first time and is immediately attacked by

concepts that either he has never studied or has forgotten many years ago: the

parts of speech.They are divided into nine categories, let’s review them:

Saturday, June 28, 2014

LA COPPA DEL MONDO—THE WORLD CUP

Vi trovate negli USA? Volete vedere una partita di calcio con altri tifosi ma non

conoscete le parole giuste? Questa lista vi aiuterà a chiacchierare con americani

che non parlano italiano:Are you in the United States? Do you want to watch a soccer game with other fans

but you don’t know the right words? This list will help you chat with Americans who

don’t speak Italian:Abbigliamento—attire:

i calzoncini—shorts

i calzini (le calze da giocatore)—socks

i guanti da portiere—goalkeeper's gloves

la maglia—shirt (jersey)

il parastinchi—shin guard

la scarpa da calcio—soccer shoe

Il campo da gioco—the soccer field:l'arbitro—referee

l'area di rigore—penalty area

la bandierina di calcio d'angolo—corner flag

il campo di calcio—field

il guardalinee—linesman

la linea di fondo—goal line

la linea di metà campo—half-way line

la linea laterale—touch line

il palo (il palo della porta)—post (goalpost)

la rete—the net

lo stadio—stadium

la traversa—crossbarI giocatori e la squadra—the players and the field:

l'ala—outside forward (winger)

l'allenatore—coach

l'allenatore in secondo—assistant coach

l'attaccante—striker

il centravanti—center forward

il centrocampista—midfield player

il commissario tecnico (CT)—head coach of the Italian National Team

il difensore—defender

il difensore esterno—outside defender

il libero—sweeper

il mediano—midfielder

la mezz'ala—inside forward (striker)

il Mister (un altro termine per CT)—another term for head coach of the Italian

National Team

il portiere—goalkeeper

la riserva (il giocatore di reserva)—substitute

lo stopper—inside defender

terzino destro/sinistro—right/left back

La partita—the game:

l'ammonizione—warning

l'arresto (della palla)—receiving the ball (taking a pass)

il calcio d'angolo (il corner)—corner (corner kick)

il calcio di punizione—free kick

il calcio di rigore (il rigore)—penalty (penalty kick)

il calcio di rinvio—goal kick

il cartellino giallo (per l'ammonizione)—yellow card (as a caution)

il cartellino rosso (per l'espulsione)—red card (for expulsion)

il cerchietto del calcio di rigore—penalty spot

il colpo di testa—header

il dribbling—dribble

il fallo—foul

fare la melina—waste time by passing the ball back and forth

il fuorigioco—offside

il gol o la rete—goal

il passaggio diretto (della palla)—pass (passing the ball)

il passaggio corto—short pass

la respinta di pugno—save with the fists

la rimessa laterale—throw-in

la rovesciata—bicycle kick

segnare un gol—to score a goal

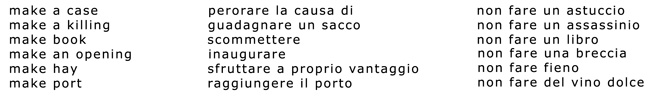

Saturday, June 21, 2014

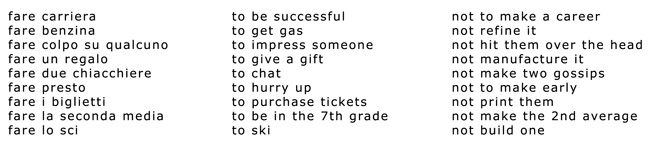

|

|

|

Let’s consider these examples: |

|

Let’s smile a little: if a native speaker of English tries to translate some of these |

Saturday, June 14, 2014

Italiano

L’altro giorno sono stata invitata a casa di amici per una partita di bocce. Abbiamo

discusso l’origine del nome; chi diceva “bacio” e chi “bocciare” e mi sono incuriosita.

Il risultato è questo:L’etimologia della parola è incerta (tanto per cambiare)!

Il Vocabolario etimologico della lingua italiana di Ottorino Piangiani dice che la

parola origina: a. dal latino Bauca o Bòcia, un tipo di vaso rotondo a collo stretto di

solito di vetro; o, b. dall’antico tedesco Bossel per una cosa gonfia.Il gioco stesso risale al 7000 a.C. in Turchia. Ci sono rappresentazioni pittoriche in

Egitto e in Grecia, ne parla Omero nell’Iliade, e agli scavi di Pompei sono state

ritrovate otto bocce e un pallino. I legionari romani portarono il gioco in Gallia e

fino in Inghilterra. Eventualmente il gioco si diffuse per tutta l’Europa. In Italia, “nel

1753 a Bologna uscì un manuale, il Gioco delle bocchie di Raffaele Bisteghi, primo

esempio di regolamentazione in lingua italiana.”Nonostante il gioco non sia né romantico come un bacio né scoraggiante come

essere bocciato, è sempre divertente.English

The other day I was invited to the home of friends for a game of bocce. We

discussed the origins of the name; there were those who said a “bacio/kiss” others

“bocciare/to flunk” so I became curious. This is the result:The etymology of the word is uncertain (so what else is new)!

The Vocabolario etimologico della lingua italiana (Etymological Dictionary of the

Italian Language) by Ottorino Piangiani states that the word originated from: a. the

Latin Bauca or Bòcia, a type of round vase usually made of glass with a tight neck;

or b. the ancient German Bossel, something swollen.The game itself dates back to 7,000 BCE in Turkey. There are pictorial depictions in

Egypt and in Greece; Homer speaks of the game in the Iliad; at the ruins of Pompeii

eight bocce balls and one “pallino” (jack or cue ball) were discovered. Roman

legionnaires brought the game to Gaul and as far as England. Eventually the game

spread throughout all of Europe. In Italy “in 1753 a manual, the Game of Bocce by

Raffaele Bisteghi was published, it is the first example of regulations in the Italian

language.”Notwithstanding that the game is neither as romantic as a kiss nor as discouraging

as flunking, it is always fun.Saturday, June 7, 2014

METTERCIItaliano

La settimana scorsa abbiamo guardato i vari usi del verbo “volerci”. Oggi

indirizziamo una forma verbale che ha legami simili quando si parla di traduzione in

inglese.Perciò "metterci" quando è usato nel contesto di tempo significa “impiegare un

periodo di tempo determinato”.Esempi:

- Quanto ci mette il treno per andare da Roma a Firenze? Ci mette almeno un

paio d’ore.- A volte Luisa ci mette un po' a capire quello che deve fare.

- Perché ci hai messo tanto tempo per finire i compiti? Non erano difficili.

- L'architetto ci ha messo solo alcuni giorni per finire il progetto della sala

d’esposizione.- Come mai ci avete messo tanto tempo ad arrivare, abitate a due passi?

"Metterci" però ha anche altri usi e significati, alcuni esempi sono:

- Ti sei ricordato di metterci il sale, ieri l’arrosto era sciapo?

- Anche se ce l’hanno messa tutta, non sono riusciti a vincere la partita.

- Finalmente ho deciso di metterci una pietra sopra.

- Una persona seria non si vergogna di metterci la faccia per una giusta causa.

- Mettiamoci d’accordo una volta per sempre.

English

Last week we looked at the various uses of the verb “volerci”. Today we will

address a verb that has similar ties when we are dealing with the English

translation.Therefore "metterci" when it is used in the context of time means “requiring a

specific period of time”.Examples:

- How much time does the train take to go from Rome to Florence? It takes at

least a couple of hours.- At times it takes Luisa a little while to understand what she needs to do.

- Why did you take so much time to finish your homework? It wasn’t difficult.

- The architect took only a few days to finish the project for the exhibition hall.

- How come it took you so much time to get here, you live around the corner?

"Metterci" however can have other uses and meanings, a few examples are:

- Did you remember to put in the salt, yesterday the roast was tasteless?

[meaning to “add”]- Even if they put everything they had into it, they weren’t able to win the

match.- I finally decided to bury it. [literally translated: to put a stone over it]

- A serious person isn’t afraid to put his best foot forward for a just cause.

[literally translated: to put his face out there]- Let’s agree once and for all.

Saturday, May 31, 2014

VOLERCIItaliano

Recentemente, in una delle mie classi abbiamo discusso il significato e l’uso del

verbo “volerci”.Quando il verbo esprime necessità, la cosa necessaria è sottintesa, per esempio

tempo, quantità, ecc. Perciò, il verbo è spesso coniugato alla terza persona

singolare o plurale.Esempi:

- Quanto ci vuole per andare da Roma a Firenze in treno? Ci vogliono almeno

un paio d’ore. (Qui, la cosa sottointesa è il tempo.)- Quanti ci vogliono per fare un tiramisù? Ce ne vogliono una ventina. (Qui, la

cosa sottintesa sono i biscotti.)Altre frasi che usano questo verbo sono:

- Ieri perdo la borsetta e oggi mi rubano il telefonino. Non ci voleva anche

questa!- Non ci vuole molto a capire che Lorenzo è un genio.

- Ce n’è voluto di sforzo, ma finalmente siamo riusciti a scalare la montagna.

- Ti ci vogliono altri due giorni di ferie per riprenderti completamente.

English

Recently, in one of my classes we discussed the significance and usage of the verb

“volerci” (meaning to need or to take).When the verb expresses necessity, the needed item is implied, for example time,

quantity, etc. Therefore, the verb is often conjugated in the third person singular or

plural.Examples:

- How long does it take to go from Rome to Florence by train? It takes at least

a couple of hours. (Here the implied item is time.)- How many are needed to make a tiramisu? About twenty (are needed).

(Here the implied item is the cookies.)Other sentences that use this verb are:

- Yesterday I lost my purse and today they steal my cellphone. That’s all I

needed!- It doesn’t take much to understand that Lawrence is a genius.

- It took a great deal of effort, but finally we were able to scale the mountain.

- You need two more days off in order to recover completely.

La morale: non è facile tradurre da una lingua all’altra; questo è il perché la

traduzione è un’arte e non una scienza.The moral: it isn’t easy translating from one language to another; this is why

translation is an art and not a science.Saturday, May 24, 2014

MAGARI: una parola usata comunemente in italiano, ma non si traduce facilmente.

Allora, cosa significa?

Magari è usata per esprimere:

1. Un desiderio: Hai comprato quell’appartamento che volevi?

Magari! C’era uno più ricco di me.2. Sì per favore/grazie: Caterina ed io andiamo fuori a cena questa sera,

prenoto un tavolo per tre?

Magari!3. Se: Magari avessi studiato italiano invece di coreano, oggi sarei a Firenze.

Magari fossi ricca!4. Forse: Magari invitiamo Lorenzo e Lisa a pranzo.

5. Piuttosto: Magari butto tutto nell’immondizia, ma loro non

avranno mai un soldo.MAGARI: a word that is commonly used but just doesn’t translate easily.

So, what does it mean?

Magari is used to express:

1. A desire: Did you buy the apartment you wanted?

I wish! There was someone richer than I.2. Yes please/thank you: Caterina and I are going out for dinner this evening,

should I reserve a table for three?

Yes please.3. If only: If only I had studied Italian instead of Korean, today I would be

in Florence.

If only I were rich!4. Maybe/perhaps: Maybe we’ll invite Lorenzo and Lisa to dinner.

5. Instead/rather: I’d rather throw everything in the garbage, but they won’t

ever get a penny.

Saturday, May 14, 2014

If Italian is indeed the language of love, how do we express it?

Ti amo = I love you

(Use this version with those you are intimately involved with: your significant

other, your spouse, your lover)

Romeo disse: “Ti amo Giulietta, più della vita stessa.”

Ti voglio bene = I love you/I like you very much

(Use this with friends and family, including parents and children)

Mamma, ti voglio bene.

Mi piaci = I like you

Mi piaci Pietro, sei simpatico e divertente.

Mi piaci tanto/molto = I like you very much

Mariangela, mi piaci tanto, sei una persona eccezionale.

Ti adoro = I adore you

Sei il mio sole e la mia luna, ti adoro.

Sono pazzo/a di te = I’m crazy about you

Sono pazzo/a di te!

BE CAREFUL:

You can love the chocolate maker but you can’t love chocolate:

Il cioccolataio si chiama Antonio, e lo amo. Mi piace la cioccolata che vende

nella sua cioccolateria, infatti, la adoro, è buonissima!

[I love the chocolate maker, his name is Antonio. I like the chocolate he sells in

his shop, in fact I love it, it’s very good!]

Saturday, May10, 2014

Falsi amici:We refer to “false friends” when we have words in one language that are similar to

those in another language but have different meanings. Here are a few basic

examples:

Italiano English

Caldo Hot (not cold) Fattoria Farm (not a factory) Libreria Bookstore (not library) Novella Short story (not a novel) Parente Relative (not parent) English Italiano

Cold Freddo Factory Fabbrica Library Biblioteca Novel Romanzo Parent Genitore

Monday, May 5, 2014

Blog Pages/Years

2025 | 2024 | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .