|

|

Blog Pages/Years

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Come si formano gli avverbi in italiano?

Per gli avverbi derivati esistono due suffissi:

--mente

--oni

Per gli avverbi che terminano in –mente ci sono i seguenti modi:

1. Prendiamo il femminile singolare di un aggettivo che al maschile termina

in “o” e aggiungiamo il suffisso “mente”.

Per esempio: simpatica + mente = simpaticamente; Maria

mi ha salutato simpaticamente; lenta + mente =

lentamente; Bisogna guidare lentamente quando piove.

2. Per gli aggettivi che terminano in -e al singolare, sono a forma unica:

aggiungiamo il suffisso “mente”

.

Per esempio: veloce + mente = velocemente; Marco ha guidato

velocemente e gli hanno dato una multa per eccesso di velocità.

3. Per gli aggettivi che hanno come ultima sillaba “le”,

“lo”, “re” e “ro” perdono la vocale finale e aggiungiamo –mente,

per esempio:

(a) “le”: difficile + mente = difficilmente

(b) “lo”: benevolo + mente = benevolmente

(c) “re”: particolare + mente = particolarmente

(d) “ro”: leggero + mente = leggermente

Per gli avverbi che terminano in–oni, questo suffisso è unito a un nome o

a un verbo si usa in un numero limitato di casi, per indicare un modo di

stare o di procedere, per esempio:

bocca = oni = bocconi. Simone ha bevuto troppo ieri sera, e si è

addormentato a bocconi.

carpare = oni = carponi. I bambini si divertono acamminare a carponi

come il loro cane.

tentare = oni = tentoni. La stanza

era così buia, che siamo dovuti avanzare a tentoni.

THE ADVERB—Part two—formation:

How do we form adverbs in Italian?

There are two suffixes for derived adverbs:

--mente--oni

For adverbs ending in -mente, there are the following forms:

1. Take the feminine singular of an adjective that ends in "o" in the

masculine and add the suffix "mente".

For example: simpatica + mente =

simpaticamente; Maria greeted me in a friendly manner; lenta + mente =

lentamente; You have to drive slowly when it rains.

2. For adjectives ending in -e in the singular, they have a unique form: add

the suffix "mente".

For example: veloce + mente = velocemente; Marco

drove rapidly and was given a speeding ticket.

3. For adjectives that end with the syllables "le," "lo," "re," and "ro", drop

the final vowel and add -mente, for example:

(a) "le": difficile + mente = difficultly

(b) "lo": benevolent + mente = benevolently

(c) "re": particolare + mente = particularly

(d) "ro": leggero + mente = slightly/lightly

For adverbs ending in -oni, this suffix is attached to a noun or verb and is

used in a limited number of cases to indicate a state of being or of

proceeding/acting,for example:

bocca =oni = bocconi. Simone drank too much last night and fell asleep

facedown.

carpare = oni = crawling. The children enjoy crawling on all fours like their

dog.

tenta = oni = groping. The room was so dark, we had to grope our way

forward.

Saturday, November 15, 2025

|

|

Se andate a cercare la traduzione di “PRESS” dall’inglese all’italiano,

state attenti, ce ne sono molte. Oggi ci limitiamo alla parola “STAMPA”.

Ci rivolgiamo al Dizionario di italiano, il Sabatini Coletti del Corriere della

Sera.

Questa parola che è stata introdotta nella lingua italiana nel secolo XV,

significa:

1. Tecnica di riproduzione in più esemplari, su carta o altro materiale, di testi

scritti, disegni o fotografie, a partire da una matrice e mediante procedimenti

diversi; l'operazione di stampare e il risultato di tale procedimento: opera in

corso di stampa || dare alle stampe, pubblicare.

2. Pubblicazione di testi stampati, soprattutto di giornali, periodici e libri || li

bertà di stampa, diritto di scrivere e pubblicare il proprio pensiero | reati di,

a mezzo stampa., quelli di diffamazione, istigazione a delinquere, offesa al

pudore ecc., commessi pubblicando testi a stampa.

3. Complesso delle pubblicazioni a carattere giornalistico: stampa quotidiana,

periodica || avere, godere di buona, di cattiva stampa, avere buona o cattiva

fama | rassegna (della) stampa, rubrica radiofonica o televisiva in cui si

presentano i titoli e i principali articoli dei giornali | ufficio stampa, in

aziende, enti, partiti, quello preposto a redigere e inoltrare comunicati agli

organi di informazione e a intrattenere relazioni con il mondo giornalistico |

comunicato stampa, dichiarazione trasmessa agli organi di informazione

giornalistica.

4. (estensione) Insieme dei giornalisti: sciopero della stampa.

5. (estensione, specialmente al plurale) Stampati di vario genere, in

particolare quelli spediti per posta: affrancatura per le stampe.

6. Riproduzione, mediante il procedimento dell'incisione, di un'opera grafica

di rilievo artistico.

7. (fotografia) Procedimento con cui si ricava dal negativo di una pellicola

una o più copie in positivo; copia positiva stampata su carta: stampa

fotografica.

8. (letterario) Carattere, indole; in senso spregiativo, sorta, specie: non

frequento gente di quella stampa.

Forse dovremmo tenere una conferenza stampa per imparare questi

significati!

If you're looking for a translation of "PRESS" from English to Italian, be

careful—there are many. Today, we will limit ourselves to the word "STAMPA."

We turn to the Italian Dictionary, the Sabatini-Coletti edition of Corriere

della Sera.

This word, which was introduced into the Italian language in the 15th

century, means:

1. The technique of reproducing written texts, drawings, or photographs in

multiple copies, on paper or other material, starting from a single matrix and

using various processes; the operation of printing and the result of this

process: work in progress || to print, to publish.

2. Publication of printed texts, especially newspapers, periodicals, and books

|| freedom of the press, the right to write and publish one's own thoughts ||

[to publish] crimes of, through the press, such as defamation, incitement to

crime, offenses against public decency, etc., committed by publishing printed

texts.

3. A group of journalistic publications: daily or periodical press || to have,

enjoy good or bad press, to have a good or bad reputation | a press review,

a radio or television program presenting newspaper headlines and most

important articles | a press office, in companies, organizations, or political

parties, responsible for drafting and forwarding press releases to the media

and maintaining relations with the journalistic world | a press release, a

statement sent to the media.

4. extension: A group of journalists: strike of the press.

5. extension: (especially in plural form) Various types of printed matter,

especially those sent by mail: postage for printed matter.

6. Reproduction: through the process of engraving, of a graphic work of

artistic importance.

7. Photography: Process by which one or more positive copies are obtained

from a film negative; positive copy printed on paper: photographic material.

8. Literary: Character, disposition; in a derogatory sense, sort, species: I

don't hang out with people of that type.

Perhaps we should hold a press conference to learn these meanings!

Saturday, October 25, 2025

|

|

| |

PERSONAGGIO O CARATTERE? PERSONAGGIO O CARATTERE?

Troppo spesso i miei studenti parlano di un “carattere” in un libro

che stanno leggendo, e ogni volta li devo correggere, la parola

corretta non è “carattere” ma “personaggio”. Questa settimana

esaminiamo la differenza tra i due.

Un personaggio è l'entità che agisce all’interno di una storia. Può

essere una persona, un animale, un oggetto o anche un'idea

astratta. Si trova in un romanzo, un film, uno spettacolo teatrale,

ecc. Viene definito anche in base al suo ruolo nella narrazione:

protagonista, antagonista, coprotagonista, secondario, comparsa,

e via dicendo.

Per esempio:

1. Nel film Il settimo sigillo di Ingmar Bergman, vediamo il

personaggio della Grande Mietitrice, la personificazione della

morte.

2. Il personaggio di Moby Dick, è entrambi una balena e una

metafora dell’ossessione del Capitano Achab.

3. L’Ispettore Salvo Montalbano è il personaggio principale dei

libri gialli di Andrea Camilleri e di una serie televisiva.

4. I personaggi della Commedia dell’arte sono facilmente

riconoscibili.

Se parliamo invece di qualità morale, natura, temperamento,

personalità, usiamo la parola carattere o indole. Quali sono il

temperamento, i desideri, le paure, le motivazioni del

personaggio? In altre parole, quali sono i tratti psicologici che

lo/la definiscono.

Per esempio:

1. Questi giorni ci sono dubbi sul carattere dei rappresentanti

governativi; è molto triste.

2. Tutti speravano che Giovanni fosse nato per fare il poliziotto,

ma aveva un carattere dolce e pacifista.

3. Chi la conosce bene, dice che Cristina ha un carattere duro ma

generoso.

4. Il personaggio Pantalone è un vecchio mercante veneziano

della Commedia dell’arte il cui carattere è avaro e lussurioso.

All too often my students use the Italian term “carattere” to refer

to a character in a book they are reading, and every time I have

to correct them, the proper term is “personaggio”. This week let’s

look at the difference between the two words.

A character (“personaggio”) is an entity that acts within a story. It

can be a person, an animal, an object, or even an abstract idea. It

appears in a novel, a film, a play, etc. It is also defined based on

its role in the narrative: protagonist, antagonist, co-star,

secondary character, extra, and so on.

For example:

1. In Ingmar Bergman's film The Seventh Seal, we see the

character of the Grim Reaper, the personification of death.

2. The character of Moby Dick is both a whale and a metaphor for

Captain Ahab's obsession.

3. Inspector Salvo Montalbano is the main character in the

detective novels by Andrea Camilleri as well as in a television

series.

4. The character Pantalone is an old Venetian merchant in the

Commedia dell’Arte whose character is miserly and lustful.

If, on the other hand, we speak of moral qualities, nature,

temperament, or personality, we use the terms “carattere” or

“indole”. What are the temperament, desires, fears, and

motivations of the character? In other words, what are the

psychological traits that define him or her?

For example:

1. These days there is doubt regarding the moral character of the

members of government; it’s very sad.

2. Everyone hoped that Giovanni was born to be a police officer,

but he had a sweet and pacifist disposition/character.

3. Those who know her well say that Cristina has a tough but

generous personality/character.

4. The character Pantalone is an old Venetian merchant in the

Commedia dell'Arte whose character is greedy and lustful.

Saturday, October 18, 2025

|

|

In inglese è facile, si aggiunge “in-law” alla parola madre, fratello, ecc. In italiano

è un’altra storia! Si dice “imparentato attraverso il matrimonio, o parente

acquisito attraverso il matrimonio” per descrivere la categoria, o parole individuali

per ciascun parente.

Ecco la lista: Ecco la lista: |

Here is the list: Here is the list: |

| cognata |

sister-in-law |

| cognato |

brother-in-law |

| genero |

son-in-law |

| marito della cugina |

cousin-in-law (male) |

| moglie del cugino |

cousin-in-law (female) |

| nuora |

daughter-in-law |

| progenero |

grandson-in-law |

| pronuora |

granddaughter-in-law |

| suocera |

mother-in-law |

| suocero |

father-in-law |

| suoceri/parenti acquisiti |

in-laws |

In English, it’s easy, we add “in-law” to the word mother, brother, etc. In Italian,

it’s an entirely different story. We say “related through marriage, or a relative

acquired through marriage” to describe the category, or individual words for

each relative.

Saturday, Septmber 18, 2025

|

|

SPENDERE E SPANDERE è una locuzione comune che indica l’atto di

sperperare denaro in modo eccessivo, senza moderazione. Per

esempio: Silvio e Melania spendono e spandono come miliardari.

Diamo un’occhiata a ciascun verbo individualmente perché hanno

significati distintivi. Secondo il Dizionario di Italiano il Sabatini

Coletti, pubblicato dal il Corriere della Sera:

SPANDERE (che è entrato a far parte del lessico nel XIII secolo)

significa:

1. Stendere in modo uniforme qualcosa su una superficie: Per

esempio: Spandere la cera sul pavimento.

2. Far cadere involontariamente qualcosa su una superficie: Per

esempio: Spandere la farina per terra.

3. (figurativamente) Emanare, diffondere qualcosa nell'ambiente

circostante: Per esempio: il caminetto spande tepore nella stanza

.

4. Divulgare notizie: Per esempio: il giornale ha spanto le notizie

dell’arresto del piromane.

Alla forma riflessiva: spandersi:

1. Diventare sempre più largo: Per esempio: la macchia si sta

spandendo.

2. Circolare, diffondersi (figurativamente): Per esempio: si sta

spandendo la voce di una tregua.

3. Diffondersi, propagarsi in un certo spazio: Per esempio: un

profumo si spande nell'aria.

SPENDERE (che è entrato a far parte del lessico nel XIII secolo)

significa:

· Versare una somma come pagamento per un acquisto, una

prestazione o un servizio; (sinonimi sono pagare, sborsare): Per

esempio: per l'acquisto della casa ho speso molto.

(figurativamente) spendere un occhio della testa, un patrimonio,

pagare una somma esagerata

· (figurativamente) Trascorrere un periodo di tempo in un certo

modo. Il complimento predicativo può essere espresso da un

gerundio: Per esempio: spendere le sere studiando; da un avverbio:

Per esempio: devi spendere bene la tua vita; da un infinito

introdotto da a: Per esempio: ho speso molto tempo a correggere i

compiti

· (figurativamente) Trascorrere il tempo in un luogo: Per esempio:

spendere la mattinata al bar; impiegare, dedicare tempo o risorse

per un dato fine, specialmente con il secondo argomento espresso

da una frase (introdotta da per): Per esempio: ha speso le sue

energie in un'impresa irrealizzabile; Potresti spendere qualche

minuto per ascoltarmi! Spendere una parola per qualcuno, parlare

a suo favore.

· Fare acquisti, spese: Per esempio: spendere nel vestire || saper

spendere, usare in modo oculato il denaro

SPENDERE E SPANDERE is a locution that translates as Spending

and squandering: This familiar verbal expression refers to the act

of wasting money excessively and without moderation. For example,

Don and Melanie “spend and squander” like billionaires.

Let’s look at each verb individually, because they have distinct

meanings. According to the Dizionario di Italiano il Sabatini Coletti,

published by il Corriere della Sera:

SPANDERE (which entered the lexicon in the 13th century) means:

1. To spread something evenly over a surface: For example: To

spread wax on the floor.

2. To accidentally drop something on a surface: For example: To

spill flour on the floor.

3. (figuratively) To emanate, spread somethinginto the surrounding

environment: For example: The fireplace spreads warmth into the

room.

4. To spread news: For example: The newspaper spread the news

of the arsonist's arrest.

In the reflexive form: to spread (itself):

1. To become increasingly larger: For example: The stain is

spreading.

2. To circulate, to spread (figuratively): For example: Word of a

truce is spreading. 3. To spread, to propagate in a defined space:

For example: A perfume spreads through the air.

SPENDERE (which entered the lexicon in the 13th century) means:

• To pay a sum of money for a purchase, service, or good;

(synonyms are to pay, to shell out): For example: I spent a lot on

buying a house. (figuratively) To spend an arm and a leg, a fortune,

to pay an exorbitant sum.

• (figuratively) To spend a period of time in a certain way. The

predicative compliment can be expressed by a gerund: For example:

To spend the evenings studying; by an adverb: For example: You

must spend your life well; by an infinitive introduced by “a”: For

example: I spent a lot of time correcting my homework.

• (figuratively) To spend time in a place: For example: To spend the

morning at the bar; to employ, dedicate time or resources to a

given goal, especially with the second argument expressed by a

clause (introduced by “per”): For example: He spent his energies

on an unattainable undertaking; Could you please take a few

minutes to listen to me? To say a word for someone, to speak in

their favor.

• To make purchases, expenses: For example: to spend on clothing

|| to know how to spend, to use money wisely

Saturday, Septmber 6, 2025

|

|

L’ORIGINE STRANIERA DEI LEMMI ITALIANI:

|

Ho incominciato questa ricerca a base di una domanda fattami da una studentessa:

“Quali sono le parole italiane derivate dal greco?” e sono finita in una tana del

coniglio. Perciò, mi limito a riprodurre una tabella di Luca Lorenzetti inclusa in uno

dei suoi saggi presenti nell’Enciclopedia dell’italiano diretta da Raffaele Simone per

la Treccani. Questa tabella conteggia i prestiti da altre lingue, sulla base del

lemmario di un grande dizionario dell’uso, il GRADIT di Tullio De Mauro

(230mila lemmi).

PROVENIENZA |

ADATTATI |

NON ADATTATI |

TOTALE |

Greco |

8342 |

13 |

8355 |

Inglese |

1989 |

4303 |

6292 |

Francese |

3517 |

1465 |

4982 |

Spagnolo |

792 |

263 |

1055 |

Tedesco |

360 |

288 |

648 |

Arabo |

430 |

203 |

633 |

Russo |

166 |

86 |

252 |

Provenzale |

240 |

|

240 |

Giapponese |

86 |

126 |

212 |

Portoghese |

161 |

48 |

208 |

Turco |

127 |

45 |

172 |

Longobardo |

114 |

|

114 |

Ebraico |

77 |

36 |

113 |

Hindi |

67 |

12 |

79 |

Sanscritto |

|

66 |

66 |

Cinese |

44 |

18 |

62 |

Persiano |

48 |

|

48 |

(Informazioni riprodotte dall’Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana fondata da

Giovanni Treccani)

I began this research based on a question a student posed: "What Italian

words are derived from Greek?" and ended up down a rabbit hole. Therefore,

I'll simply reproduce a table by Luca Lorenzetti found in one of his essays in the

Enciclopedia dell'italiano edited by Raffaele Simone for Treccani. This table lists

loanwords from other languages, based on the glossary of a major usage

dictionary, Tullio De Mauro's GRADIT (230,000 entries).

Terms of foreign origin in Italian:

PROVENANCE |

ADAPTED |

NOT ADAPTED |

TOTAL |

Greek |

8342 |

13 |

8355 |

English |

1989 |

4303 |

6292 |

French |

3517 |

1465 |

4982 |

Spanish |

792 |

263 |

1055 |

German |

360 |

288 |

648 |

Arabic |

430 |

203 |

633 |

Russian |

166 |

86 |

252 |

Provencal |

240 |

|

240 |

Japanese |

86 |

126 |

212 |

Portuguese |

161 |

48 |

208 |

Turkish |

127 |

45 |

172 |

Langobardic |

114 |

|

114 |

Hebrew |

77 |

36 |

113 |

Hindu |

67 |

12 |

79 |

Sanskrit |

|

66 |

66 |

Chinese |

44 |

18 |

62 |

Persian |

48 |

|

48 |

(Information reproduced from the Institute of the Italian

Encyclopedia founded by Giovanni Treccani)

Saturday, August 23, 2025

|

|

LA POSIZIONE DEGLI AGGETTIVI INDIVIDUALI—Parte 4

Come abbiamo visto in precedenza, a differenza dall’inglese dove

gli aggettivi di solito precedono il sostantivo, in italiano la loro

posizione varia a seconda della loro funzione. In alcuni casi, la

posizione dell’aggettivo cambia il suo significato. Ecco la

continuazione di alcuni degli aggettivi più comuni in questa

categoria:

As we have already seen, unlike English where adjectives usually

precede the noun, in Italian their position varies depending on

their function. In some cases, the placement of the adjective

changes its meaning. Here is a continuation of some of the most

common adjectives in this category:

| PRIMA DEL SOSTANTIVO |

SIGNIFICATO/MEANING |

DOPO IL SOSTANTIVO |

SIGNIFICATO/MEANING |

| Una leggera ferita |

A slight wound |

Una valigia leggera |

A light-weight suitcase |

| Il massimo rispetto |

The utmost respect |

La velocità massima |

The maximum speed/speed limit |

Un povero uomo |

An unfortunate man |

Un uomo povero |

A poor man |

La stessa ragazza |

The same girl |

La ragazza stessa |

The girl herself |

Una semplice domanda |

A mere/simple question |

Una domanda semplice |

An easy question |

L’unica occasione |

The only opportunity |

Un’occasione unica |

A unique opportunity |

L’unico figlio |

The only child |

Figlio unico |

A one-of-a-kind child |

Varie volte |

Several times/sometimes |

Un panorama vario |

A varied panorama |

Un vecchio amico |

A longstanding/old friend |

Un amico vecchio |

An old (aged) friend |

Adesso tocca a voi usarli in una frase per impararli meglio.

Now it’s your turn to use them in a sentence to better learn them.

Saturday, August 9, 2025

|

|

Come abbiamo visto in precedenza, a differenza dall’inglese dove gli aggettivi di

solito precedono il

sostantivo, in italiano la loro posizione varia a seconda della

loro funzione. In alcuni casi, la posizione dell’aggettivo cambia il suo significato.

Ecco alcuni degli aggettivi più comuni in questa categoria:

As we have already seen, unlike English where adjectives usually precede the

noun, in Italian their position varies depending on their function. In some cases,

the placement of the adjective changes its meaning. Here are some of the most

common adjectives in this category:

| PRIMA DEL SOSTANTIVO |

SIGNIFICATO/MEANING |

DOPO IL SOSTANTIVO |

SIGNIFICATO/MEANING |

| Gli antichi greci |

The ancient Greeks |

Un vaso antico |

An old/antique vase |

| Un alto ufficiale |

A high-ranking officer |

Una ragazza alta |

A tall girl |

| L’alta Italia (il settentrione) |

Northern Italy |

Un muro alto |

A high wall |

| La bassa Italia (il meridione) |

Southern Italy |

Una donna bassa |

A short woman |

| Il basso Po |

The lower (part) of the river |

Po Un voto basso |

A low grade (as on a test) |

|

Una cara amica |

A dear friend |

Una cena cara |

An expensive dinner |

| Certe notizie |

Some news |

Notizie certe |

Reliable news |

| Un discreto risultato |

A good/decent result |

Un prezzo discreto |

A reasonable price |

| Una discreta età |

A considerable age |

Una domanda discreta |

A discrete question |

| Diversi libri |

Several books |

Libri diversi |

Different books

|

Adesso tocca a voi di usarli in una frase per impararli meglio. La prossima volta

vedremo altri di questi

aggettivi. Divertitevi!

Now it’s your turn to use them in a sentence to better learn them. Next time we

will see moreof these types of adjectives. Have fun!

Saturday, July 26, 2025

|

|

LA POSIZIONE DEGLI AGGETTIVI INDIVIDUALI—Parte 2

Molti aggettivi italiani possono precedere o seguire il sostantivo a seconda

della loro funzione: 1.specificante o restrittiva oppure 2. generica. Gli

aggettivi generici sono usati a scopo descrittivo, retoricoo metaforico. La

maggior parte degli aggettivi che appartengono a questa categoria ha

significati piuttosto ampi. La loro flessibilità permette di variare il loro

significato a seconda del contesto. Alcuni degli aggettivi più comuni sono:

anziano, bello, brutto, buono, cattivo, giovane, grande, lungo, nuovo,

piacevole, piccolo, simpatico, strano. Quando sono posti prima del sostantivo

forniscono una descrizione generica e soggettiva; quando sono posti dopo,

individuano e identificano caratteristiche specifiche.

Esempi:

|

PRIMA DEL NOME: |

DOPO IL NOME: |

| |

|

descrizioni generiche/soggettive

|

funzione specificativa: oggettiva |

| È una grande amica. |

Ho molta sete, vorrei un bicchiere grande d'acqua. |

| È una buona soluzione. |

È una soluzione buona. |

| Maria si è comprata un bel vesitito. |

Maria si è messa il vestito bello questa sera. |

| C'è una lunga fila alla biglietteria. |

Ho scelto la gonna lunga rossa. |

| Tutto il santo giorno. |

Lo Spirito Santo. |

THE POSITION OF SINGLE ADJECTIVES—Part 2

Many Italian adjectives can precede or follow the noun depending on

their function: 1. If it isspecifying or restrictive or 2. Generic. Generic

adjectives are used for descriptive, rhetorical or metaphorical purposes.

Most of the adjectives that belong to this category have fairly broad

meanings. Their flexibility allows them to vary their meaning depending

on the context. Some of the most common adjectives are: old, beautiful,

ugly, good, bad, young, big, long, new, pleasing, small, nice, strange.

When they are placed before the noun they provide a generic, subjective

description; when placed after they pinpoint and identify specific

characteristics.

Examples:

| BEFORE THE NOUN: |

AFTER THE NOUN: |

| |

|

| generic/subjective descriptions |

specifying function: objective |

| She is a great friend. |

I’m very thirsty, I would like a large glass of water. |

| It’s a good result. |

It’s a right/good result. |

| Mary bought herself a lovely dress. |

Mary put on her best dress this evening. |

| There’s a long line at the ticket window. |

I chose the long red skirt. |

| The whole blessed day. |

The Holy Spirit. |

Saturday, July 12, 2025

|

|

LA POSIZIONE DEGLI AGGETTIVI INDIVIDUALI—Parte 1

A differenza dall’inglese dove gli aggettivi di solito precedono il sostantivo, in

italiano la loro posizione varia a seconda della loro funzione.

Siccome c’è molto da spiegare, divido questo tema in 3 parti.

La maggior parte degli aggettivi descrittivi italiani seguono il nome quando

hanno una funzione specifica, cioè quando evidenziano caratteristiche

specifiche o tratti distintivi del nome.

1. Aggettivi che indicano una categoria (spesso derivano da un sostantivo).

Ad esempio: la guerra mondiale; un cane di razza; una crisi politica; uno

sperimento chimico

2. Aggettivi che indicano nazionalità o origine, religione, ideologia. Ad

esempio: una donna messicana, uno studente abruzzese, una chiesa battista,

un partito liberale

3. Aggettivi che indicano colore, forma, disegno, materiale. Ad esempio: una

gonna verde, una palla rotonda, una giacca a righe, un cappotto di lana, una

piazza polverosa

4. Aggettivi derivati da un participio passato (di solito terminanti in -ato, -ito,

o -uto) e alcuni derivati da un participio presente (terminanti in -ante o -ente).

Ad esempio: una strada bagnata, un piatto pulito, una commissione compiuta,

un amico tollerante, una tazza di caffè bollente

5. Aggettivi con suffisso come -ino o -etto. Ad esempio: un gattino piccolino,

una bambina furbetta

6. Aggettivi usati con un avverbio: molto, abbastanza, piuttosto, troppo, poco.

Ad esempio: una donna molto simpatica, un libro abbastanza interessante, un

articolo troppo lungo, un’artista poco conosciuta

7. Sintagmi aggettivali che di solito fanno parte dei punti 1, 2 e 3 sopra. Un

sintagma aggettivale è un gruppo di parole che funge da aggettivo per

modificare un nome o un pronome. Ad esempio: un esame sorprendentemente

facile, pochissimi suggerimenti utili, una storia d'amore

Unlike English where adjectives usually precede the noun, the majority of

Italian descriptive adjectives follow the noun when they have a specifying

function, i.e. when they pinpoint specific characteristics or distinguishing

features of the noun.

1. Adjectives denoting a category (the are often derived from a noun). For

example: the world war; a purebred dog; a political crisis; a chemical

experiment

2. Adjectives denoting nationality or origin, religion, ideology. For example: a

Mexican woman, a student from Abruzzo, a Baptist church, a liberal party

3. Adjectives denoting color, shape, design, material. For example: a green

skirt, a round ball, a striped jacket, a wool coat, a dusty square

4. Adjectives derived from a past participle (usually ending in -ato,

-ito, or -uto) and some derived from a present participle

(ending in -ante or -ente). For example: a wet road, a clean plate, an errand

done, a tolerant friend, a cup of hot coffee

5. Adjectives with a suffix like -ino or -etto. For example: a little kitten, a

clever little girl

6. Adjectives used with an adverb—very, quite, rather, too, little. For example:

a very nice woman, a fairly interesting book, a too-long article, a little-known

artist

7. Adjectival phrases which are usually part of 1, 2 and 3 above. An adjectival

phrase is a group of words that functions as an adjective to modify a noun or

pronoun. For example: a surprisingly easy test, a very few helpful hints, a

love story

Saturday, June 28, 2025

|

|

C’è una parola che piace molto ai miei studenti: FIGURATI.

Il significato cambia secondo l’uso.

1. Figurati = prego

Questo è l’uso più semplice e comune; per esempio:

· Massimiliano: “Grazie per esserti ricordata del mio

compleanno.”

Caterina: “Figurati.”

· Massimiliano: “Veramente, non soltanto un biglietto

di auguri, ma anche un mazzo di fiori. Sei gentilissima!”

Caterina: “Ma figurati. Veramente, è un piacere.”

2. Figurati = assolutamente no

È usato in questo senso per una negazione fortissima; per esempio:

· Domanda: “Che ne pensi se andiamo in Egitto per le ferie d’agosto?”

Risposta: “Sei pazzo, figurati se vado lì in piena estate, lo sai che non sopporto

il caldo.”

· Domanda: “Secondo te, Maddalena e Pietro si sposeranno?”

Risposta: “Figurati, non fanno altro che litigare!”

3. Figurati = ma va, non credo

È usato in questo senso per esprimere dubbio o incertezza; per esempio:

· Domanda: “È già arrivata Elisabetta?”

Risposta: “Di solito è in ritardo, figurati se riesce ad arrivare in orario.”

· Domanda: “Quest’anno per il compleanno di Massimiliano, pensi di organizzare

una festa?”

Risposta:“Figurati. Perché non ci pensi tu?”

4. Figurati = non ti preoccupare, non ci sono problemi

È usato in questo senso per far sentire meglio qualcuno per una mancanza; per

esempio:

· Caio*: “Scusami Gelsomina se ho vuotato il sacco riguardo alla festa a

Massimiliano.”

Gelsomina: “Figurati, Massimiliano ne era già al corrente, era Tizio* il primo a

dirglielo!”

· Sempronio*: “Mi dispiace se ho fatto un macello.”

Giovanna: “Figurati, per fortuna era solo mezzo bicchiere d’acqua, non vino rosso!”

There is a word that my students like very much:FIGURATI.

It’s meaning varies according to its use.

1. Figurati = you are welcome

This is its simplest and most common use. For example:

• Maximilian: “Thank you for remembering my birthday.”

Catherine: “Figurati.”

• Maximilian: “Really, not only a birthday card, but a bouquet of flowers as well.

You are very kind!”

Catherine: “But figurati. Truly, it’s a pleasure.”

2. Figurati = absoultely not

In this case it is used as a very strong denial. For example:

• Question: “What do you think if we go to Egypt for summer vacation?”

Answer: “Are you crazy, figurati if I would go there in the height of summer.

You know I can’t stand the heat.”

• Question: “What do you think, will Maddalena and Peter get married?”

Answer: “Figurati, all they do is fight!”

3. Figurati = no way, I don’t think so

In this case it is used to express doubt or uncertainty. For example:

• Question: “Has Elisabetta arrived yet?”

Answer: “She’s usually late, figurati if she can arrive on time.”

• Question: “This year, for Maximilian’s birthday, are you thinking about

throwing him a party?”

Answer: “Figurati. Why don’t you take care of it?”

4. Figurati = don’t worry, no problem

In this case it is used to help someone feel better for an error they committed.

For example:

• Tom*: “Forgive me Jasmine if I spilled the beans regarding Max’s party.”

Jasmine: “Figurati, Max knew about it already, Dick* was the first to tell him!”

• Harry*: “I’m sorry if I made a mess.”

Joanne: “Figurati, luckily it was only a glass of water, not red wine!”

*Tizio, Caio & Sempronio translate into English as Tom, Dick & Harry.

Saturday, June 14, 2025

|

|

Quali sono le derivazioni di parole che terminano in -ISTA E -ISTICO?

Ci riferiamo all’enciclopedia Treccani per una spiegazione dettagliata.

Siccome si tratta di due suffissi diversi, divido il chiarimento in due parti.

Oggi parliamo di -ISTICO.

Il suffisso -istico è composto da -ista + -ico (dal latino -icus, a sua volta

dal greco -ikòs).

- Si trova in aggettivi formati modernamente:

arte ▶ artistico

calcio ▶ calcistico

- Per lo più connessi con nomi in -ista:

alpinista ▶ alpinistico

egoista ▶ egoistico

turista ▶ turistico

- Alcuni aggettivi in -istico possono assumere una connotazione

spregiativa

elettorale ▶ elettoralistico

intellettuale ▶ intellettualistico

- La forma femminile sostantivata -istica è usata nella formazione di

nomi di discipline, tecniche, metodologie o attività, spesso a partire da

forme in -ista o -istico

anglista ▶ anglistica (‘disciplina che studia la letteratura

inglese’) inglese’)

favolistico ▶ favolistica (‘disciplina che studia le favole’)

oculista ▶ oculistica (‘branca della medicina che si occupa

dell’occhio’) dell’occhio’)

- Ma anche a partire da altre parole

componente ▶ componentistica

infortunio ▶ infortunistica

- L’uso si è spinto fino a un valore puramente collettivo

manuale ▶ manualistica (‘insieme dei manuali su un dato

argomento’) argomento’)

oggetto ▶ oggettistica (‘insieme degli oggetti, soprattutto

per la casa’) per la casa’)

trattato ▶ trattatistica (‘insieme dei trattati su una

determinata disciplina’) determinata disciplina’)

- Una variante del suffisso -istico è la forma -astico, che può essere

usata se la base termina in -a

orgia ▶ orgiastico

prosa ▶ prosastico.

Dubbi:

Esistono alcune coppie di aggettivi in -ista / -istico:

entusiasta / entusiastico

femminista / femministico

imperialista / imperialistico

positivista / positivistico

socialista / socialistico

Per lo più si tratta di sinonimi, in cui è difficile distinguere una sfumatura di

significato e di registro. Talora si può cogliere, soprattutto con l’aiuto del

contesto, nell’aggettivo in -istico una sfumatura leggermente dispregiativa.

1. It is found in modern adjectives:

art ▶ artistic

soccer ▶ football

2. Of which, most of them are connected to nouns ending in -ista:

mountaineer ▶ mountaineering

egoist ▶ egoistic

tourist ▶ touristic

3. Some adjectives ending in -istico can take on a derogatory connotation

electoral ▶ electoral

intellectual ▶ intellectualistic

4. The feminine noun form -istica is used in the formation of names of

disciplines, techniques, methodologies or activities, often starting from forms

ending in -ista or -istico

Anglist ▶ Anglo studies (‘discipline that studies English

literature’) literature’)

fables ▶ folk tales (‘discipline that studies fables’)

ophthalmologist ▶ ophthalmology (‘branch of medicine that

deals with the eye’) deals with the eye’)

5. But also starting from other words

component ▶ components

injury ▶ industrial accident research/accident prevention studies

6. The use has even reached a purely collective value

manual ▶ manuals (‘set of manuals on a given subject’)

object ▶ objects (‘set of objects, especially for the home’)

treatise ▶ treatises (‘set of treatises on a given discipline’)

7. A variant of the suffix -istic is the form -astico, which can be used if

the base word ends in -a the base word ends in -a

orgy ▶ orgiastic

prose ▶ prostatic.

DOUBTS:

There are additionally some pairs of adjectives ending in -ist / -istic:

enthusiast / enthusiastic

feminist / feminist

imperialist / imperialistic

positivist / positivistic

socialist / socialistic

For the most part these are synonyms, where it is difficult to distinguish

nuances of meaning and register. Sometimes, especially with the help of the

context, a slightly derogatory nuance can be detected in the adjective ending

in -istic.

https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/ista-e-istico_(La-grammatica-italiana)

Saturday, May 31, 2025

|

|

|

Quali sono le derivazioni di parole che terminano in -ISTA E -ISTICO?

Ci riferiamo all’enciclopedia Treccani per una spiegazione dettagliata.

Siccome si tratta di due suffissi diversi, divido il chiarimento in due

parti.

Il suffisso -ista deriva dal latino -ista (a sua volta dal greco -istès) e

indica la persona che svolge un’attività, segue un’ideologia o presenta

determinate caratteristiche.

- Si trova in parole composte derivate dal greco o dal latino

(protagonista, artista), ma soprattutto in parole formate

modernamente:

bar ~ barista

femmina ~ femminista

discesa ~ discesista

- Tanto che lo si trova molto spesso nei neologismi (termini o

costrutti di recente introduzione nella lingua)

pidduista ‘affiliato alla loggia massonica P2’

cerchiobottista ‘chi evita di compiere una scelta’ (dal

detto dare un colpo al cerchio e uno alla botte) [Il significato di questo

proverbio usato spesso in modo ironico o canzonatorio, descrive il

comportamento di una persona che, in una situazione di disaccordo,

non prende la parte di nessuno, a volte dando ragione all’uno o

all’altro.]

- Le parole derivate che rinviano a correnti di pensiero politiche,

ideologiche, religiose, letterarie, artistiche possono presentare

anche un uso aggettivale:

il partito comunista

la poesia futurista

la Chiesa battista

- In alcuni casi la base è un aggettivo accompagnato da un nome

che ne delimita l’applicazione

civilista (‘chi si occupa di diritto civile’) civilista (‘chi si occupa di diritto civile’)

correntista (‘chi ha un conto corrente’) correntista (‘chi ha un conto corrente’)

https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/ista-e-istico_

(La-grammatica-italiana)

What are the derivations of words that end in -ISTA AND -ISTICO?

We refer to the Treccani encyclopedia for a detailed explanation. Since

these are two different suffixes, I will divide the clarification into two

parts.

The suffix -ista derives from the Latin -ista (in turn from the

Greek -istès) and indicates the person who carries out an activity,

follows an ideology or presents certain characteristics.

- It is found in compound words derived from Greek or Latin

(protagonist, artist), but above all in modern words:

bar ~ barista

female ~ feminist

descent ~ downhill skier (downhiller)

- So much so that it is very often found in ➔neologisms (terms

newly added to a language)

pidduista ‘affiliated to the P2 Masonic lodge’ pidduista ‘affiliated to the P2 Masonic lodge’

[an interesting bit of Italian history, perhaps for another time]

cerchiobottista ‘one who avoids making a choice’ (from the saying

give one blow to the circle/hoop and one to the barrel) [The meaning of

this proverb, often used in an ironic or mocking way, describes the

behavior of a person who, in a contentious situation does not take sides,

sometimes agreeing with one or the other.]

- Derived words that refer to political, ideological, religious, literary,

artistic currents of thought can also have an adjectival use

the Communist party

Futurist poetry

The Baptist Church

- In some cases, the base is an adjective accompanied by a noun

that delimits its application

Civil lawyer “civilista” (‘one who specializes in civil law’)

Account holder “correntista” (‘one who has a checking Account holder “correntista” (‘one who has a checking

account’) account’)

Saturday, May 12, 2025

|

|

- Per segnalare l'elisione: la vocale finale di una parola che è eliminata

quando la parola successiva comincia con vocale.

Per esempio: L’amico di Claudia si chiama Stefano.

L’elefante è un animale magnifico.

Vorrei visitare l’isola di Capri l’anno prossimo.

Quest’anno al Teatro alla Scala di Milano danno l’opera

Rigoletto. Rigoletto.

L’ultima volta che sona andata in Italia mi sono divertita

un mondo. un mondo.

Susanna è un’infermiera molto paziente.

- Con i pronomi diretti lo e la.

Per esempio: L’ho visto ieri al cinema. (lui)

L’hanno comprata l’anno scorso a Fregene. (la casa)

- In una serie d’imperativi in cui si è persa la vocale finale:

Per esempio: “Marta, da’ il tuo quaderno alla maestra!” (dal verbo dare) Per esempio: “Marta, da’ il tuo quaderno alla maestra!” (dal verbo dare)

“Per favore, di’ tutto quello che hai fatto a tua madre!” (dal

verbo dire) verbo dire)

“Quante volte te lo devo dire, fa’ il bravo!” (dal verbo fare)

“Ti prego, sta’ zitto, ho un terribile mal di testa.” (dal verbo

stare) stare)

“Va’ via, non ne posso più!” (dal verbo andare) “Va’ via, non ne posso più!” (dal verbo andare)

- Per marcare il troncamento in alcune formule standardizzate

Per esempio: un po’ per un poco; va be’ per va bene.

- Quando manca la prima vocale o la riduzione di un numero.

Per esempio: zio ‘Ntonio per zio Antonio; Maddalena è nata tre anni fa, cioè nel Per esempio: zio ‘Ntonio per zio Antonio; Maddalena è nata tre anni fa, cioè nel

’14 per 2014. ’14 per 2014.

- Con c’è, e c’era.

‘’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’’

The apostrophe is used in Italian:

- When there is an elision: the vowel at the end of a word is eliminated when

the following word begins with a vowel.

For example: The name of Claudia’s friend is Stefano. For example: The name of Claudia’s friend is Stefano.

The elephant is a magnificent animal.

I would like to visit the island of Capri next year.

This year at the Scala in Milano, they are staging the opera

Rigoletto. Rigoletto.

The last time I went to Italy, I had lots of fun.

Susan is a very patient nurse.

- With the direct object pronouns lo and la.

For example: I saw him yesterday at the movies. For example: I saw him yesterday at the movies.

They bought it last year at Fregene. (the house)

- With a series of imperatives where the final vowel is missing.

For example: “Marta, give your notebook to the teacher!”

“Please, tell your mother everything you did!”

“How many times do I have to say it, behave!”

“I beg you, be quiet, I have a terrible headache!”

“Go away, I can’t take it anymore!”

- To signal an apocope in several standardized formulas:

For example: un po’ for a little; va be’ for it’s fine For example: un po’ for a little; va be’ for it’s fine

- When the first vowel is missing or when a number is reduced.

For example: zio ‘Ntonio for Uncle Antonio; Maddalena was born three years ago, For example: zio ‘Ntonio for Uncle Antonio; Maddalena was born three years ago,

that is in ’14, for 2014 that is in ’14, for 2014

Saturday, May 3, 2025

|

|

PROUD = FIERO O ORGOGLIOSO?

Per lo più, ORGOGLIOSO e FIERO hanno lo stesso significato quando sono

usati positivamente.

FIERO significa essere soddisfatto di sé o di altri.

Per esempio: Sono molto fiera di te, Gelsomina, hai suonato il

violino a perfezione. violino a perfezione.

Devi essere molto fiero di te stesso Stefano, hai vinto la

partita di tennis contro un partita di tennis contro un

avversario impressionante.

FIERO è sempre positivo.

In oltre, il Dizionario del Corriere della Sera, il Sabatini Coletti ci dice: FIERO

1. Esprime, dimostra fermezza morale, grande dignità e orgoglio: carattere,

sguardo fiero; coraggioso, intrepido: un popolo fiero;

2. Profondamente orgoglioso di qualcuno o qualcosa: sono fiero di mio figlio;

3. In letteratura: Orrendo, feroce, selvaggio, anche bestiale. (Un breve

inciso: Una fiera è un animale feroce; ma si trova solo nella letteratura—

pensiamo al 1° canto dell’Inferno di Dante, dove incontra le tre fiere: la

lonza, il leone e la lupa.)

Anche ORGOGLIOSO significa essere soddisfatto di sé, avere un forte senso

di autostima.

Per esempio: Io sono orgogliosa di essere italiana.

Attenti però, ORGOGLIOSO può avere anche una connotazione negativa,

qualcosa come "superbo o arrogante". Un orgoglio eccessivo è chiamato

“superbia”, e un orgoglio ingiustificato è vanità e/o arroganza.

Per esempio: Il presidente del consiglio d’amministrazione è troppo

orgoglioso per riconoscere i orgoglioso per riconoscere i

propri errori; chissà dove andrà a finire la ditta!

PROUD = FIERO or ORGOGLIOSO? Mostly, ORGOGLIOSO and FIERO

have the same meaning when used positively.

FIERO means to be pleased with oneself or others.

For example: I am very proud of you, Gelsomina, you played the

violin perfectly. violin perfectly.

You must be very proud of yourself Stefano, you won the

tennis match against an impressive opponent. tennis match against an impressive opponent.

FIERO is always positive.

In addition, the Dictionary of the Corriere della Sera, Sabatini Coletti tells

us: FIERO

1.Expresses, demonstrates moral firmness, great dignity and pride:

a proud character or look; courageous, intrepid: a proud people; a proud character or look; courageous, intrepid: a proud people;

2. Deeply proud of someone or something: I am proud of my son;

3. In literature: horrible, ferocious, wild, even bestial. (A brief aside:

“Una fiera” (a wild beast) is a ferocious animal; but it is found only

in literature—think of the 1st canto of Dante's Inferno,

where he meets the three wild beasts: the leopard, the lion and the

she-wolf.)

ORGOGLIOSO also means to be satisfied with oneself, to have a strong

sense of self-esteem.

For example: I am proud to be Italian.

But be careful, ORGOGLIOSO can also have a negative connotation,

something like "haughty/arrogant". Excessive pride is "haughtiness", and

unjustified pride is vanity and/or arrogance.

For example: The chairman of the board of directors is too proud

to recognize his own mistakes;

who knows where the company will end up!

Saturday, April 5, 2025

|

|

| |

TRA O FRA?

Un proverbio italiano dice: “Tra il dire e il fare c’è di mezzo il mare.”

Quado si usa “tra” e “fra”? C’è una differenza?

Oggigiorno non c’è una differenza, e le preposizioni tra e fra hanno

esattamente lo stesso significato. Siccome la loro frequenza d’uso è

simile, la scelta è arbitraria. Però è importante evitare i suoni ripetitivi;

per esempio:

- tra fratelli e non fra fratelli

- fra tre anni e non tra tre anni

- il treno fra Trieste e Trento e non il treno tra Trieste e Trento

- tra Firenze e Fiesole e non fra Firenze e Fiesole

Ma se controlliamo il dizionario del Corriere della Sera, troviamo questa

spiegazione molto interessante: “La preposizione fra discende dal latino

infra, propriamente “sotto”, “di sotto”, opposta a supra, “sopra”, “oltre”;

ha dunque subìto un cambio di significato nel passaggio all’italiano. Tra

deriva invece da intra, “in mezzo”, “dentro”. Oggi, si capisce, tra e fra

hanno lo stesso significato.”

An Italian proverb states: “Between saying and doing there is the sea.”

[That’s the literal translation; it means something along the lines of:

Easier said than done. The road to hell is paved with good intentions.

Actions speak louder than words. Etc.] When do we use “tra” and “fra”?

Is there a difference?

Nowadays there is no difference, and the prepositions tra and fra have

precisely the same meaning. Since their frequency of usage is similar,

the choice is arbitrary. However, it is important to avoid repetitive

sounds, for example:

- between brothers

- in three years

- the train between Trieste and Trento

- between Florence and Fiesole

If we check the dictionary from Corriere della Sera we find this very

interesting explanation: “The preposition fra comes from the Latin infra,

meaning “under”, “underneath”, as contrasted to supra, “above”,

“beyond”; it has undergone a change of meaning when it passed into

Italian. Tra comes from intra, “in the middle”, “inside”. Today, we

know, tra and fra have the same meaning.”

Saturday, March 22, 2025

|

|

| |

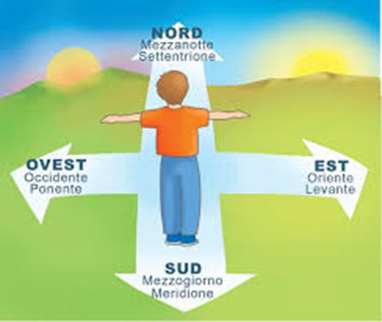

Da dove derivano i sostantivi “Meridione” e “Settentrione”?

Si deve iniziare con i quattro punti cardinali, cioè il nord o settentrione, il

sud o meridione, l'est o oriente e l'ovest o occidente.

Il Meridione è il punto cardinale corrispondente al sud e deriva dal termine

latino “meridiem”, l’orario del mezzogiorno. La ragione è dovuta al fatto che

a quell’ora del giorno il sole si trova verso sud per tutti i popoli dell’emisfero

nord (anche detto boreale o settentrionale). Per questa ragione il Meridione è

anche chiamato il Mezzogiorno.

La parola Settentrione deriva dal termine latino “septemtriones” che significa

i sette buoi da lavoro, il modo in cui i romani antichi chiamavano le sette

stelle della costellazione Orsa Maggiore o Gran Carro.

Where do the nouns “Meridione” and “Settentrione” come from? These are

the names used to call Southern Italy and Northern Italy respectively.

We have to begin with the four cardinal or compass points, in other words:

North (or settentrione in Italian), South (or meridione in Italian), East and

West.

Meridione is the cardinal point which corresponds to the south and takes its

name from the Latin “meridiem”, the noon hour. The reason is due to the

fact that at that time of day the sun can be found towards the south for all

peoples who inhabit the northern hemisphere. For this reason, Meridione is

also called Mezzogiorno (noon).

The word Settentrione comes from the Latin “septemtriones” which means

the seven oxen, the way in which the ancient Romans called the seven stars

of the Constellation Ursa Major or Great Cart.

Saturday, March 8, 2025

|

|

| |

Queste quattro parole spesso confondono gli studenti americani perché se

guardano nel loro dizionario per la traduzione di “good” trovano almeno

queste possibilità.

Così vale la pena ripassarne l’uso un’altra volta.

Bravo quando è usato da aggettivo, descrive esseri viventi: persone o

animali, le loro qualità, abilità, il loro valore. Non è usato per descrivere

cose inanimate.

- Gemma è una brava cuoca.

- Fido è un bravo cane.

- Alessandra e Diana sono brave studentesse.

- Cristoforo e Giacomo sono bravi pasticceri.

Buono quando è usato da aggettivo, esprime un giudizio, descrive una qualità:

- Abbiamo mangiato dei buoni biscotti e bevuto un buon caffè per colazione.

- Cristina è proprio una buon’amica.

- Hanno fatto un buon affare quando hanno comprato quella casa in città.

- Questo sciroppo è buono per la tosse.

Bello è un aggettivo che descrive un aspetto estetico di un sostantivo o

esprime un giudizio positivo. Ricordiamoci che qui stiamo parlando della

traduzione a “good” in inglese, non a “beautiful”.

- Sabato scorso abbiamo visto un bel film.

- Leggiamo delle belle novelle di Luigi Pirandello in classe.

- Ieri ha fatto bel tempo.

Bello è anche usato per intensificare un’idea:

- Mi sono preparata un bel piatto di spaghetti alle vongole.

- Fa un freddo cane, mi faccio una bella doccia per riscaldarmi.

- Marco ha deciso di farsi un bel pisolino prima di uscire questa sera.

- Hai combinato proprio un bel guaio.

Bene invece è un avverbio e perciò descrive un verbo o un aggettivo.

- Abbiamo mangiato bene a casa vostra domenica scorsa, grazie mille.

- L’esame è andato bene, benissimo, infatti, Teresa ha ricevuto 30 e lode.

- Oggi tutto va da bene in meglio, che fortuna!

- Dopo 24 ore senza sonno, loro hanno dormito proprio bene.

La confusione subentra quando incontriamo espressioni come:

These four words often confuse American students because if they look up

the translation for “good” in their dictionaries they will find at least these

four possibilities: bravo, buono, bello, or bene. Therefore, it’s a good idea

to review their uses once again.

Bravo when it is used as an adjective describes living things: persons or

animals. It is not used to describe inanimate objects.

- Gemma is a good cook.

- Fido is a good dog.

- Alessandra and Diana are good students.

- Cristoforo and Giacomo are good bakers.

Buono when it is used as an adjective expresses a judgment or describes a

quality.

- We ate several good cookies and drank good coffee for breakfast.

- Cristina is really a good friend.

- They made a good deal when the bought that house in town.

- This cough syrup is really good (for coughs).

Bello is an adjective that describes an esthetic aspect of a noun or

expresses a positive judgment. Remember that we are referring to the

translation of “good” from the English, not “beautiful”.

- Last Saturday we saw a good movie.

- We are reading some good short stories by Luigi Pirandello in class.

- Yesterday the weather was good.

Bello is also used to intensify an idea:

- I prepared a nice plate of spaghetti with clams for myself.

- It’s freezing; I’m going to take a nice shower to warm myself up.

- Marco decided to take a nice nap before going out this evening.

- You sure did make a big mess.

Bene on the other hand, is an adverb and therefore describes a verb or an

adjective.

- We ate well at your house last Sunday, thank you very much.

- The exam went well; very well in fact, Teresa received an A+.

- Today everything is getting better and better, what luck!

- After 24 hours without sleep, they slept really well.

Confusion can occur when we come across expressions like:

- The bravi in Alessandro Manzoni’s novel The Betrothed are bad guys.

- The store gave me a coupon rather than a refund.

I never have a minute of peace and quiet when they come to visit me.

Saturday, February 22, 2025

|

|

I PUPI SICILIANI—Parte III I PUPI SICILIANI—Parte III

Se vi ricordate, vi ho detto che mentre facevo delle ricerche sul

tema di marionette, burattini e pupi ho trovato, sul sito del

Comune di Catania, un articolo interessante intitolato Storia dei

Pupi Siciliani scritto dal Prof. Alessandro Napoli. Avendo introdotto

il tema e elencato gli elementi della tradizione palermitana, oggi

esaminiamo quelli della tradizione catanese.

[https://www.comune.catania.it/la-citta/tradizioni/pupisiciliani]

LA TRADIZIONE CATANESE

-

Dimensioni dei pupi: da cm. 80 fino a m.1.30 di altezza.

-

Peso: fino a Kg. 35 circa.

-

Caratteristiche della meccanica: gambe rigide, senza snodo al

ginocchio; se il pupo è un guerriero, la spada è quasi sempre

impugnata nella mano destra.

-

Sistema di manovra: dall’alto di un ponte posto dietro i fondali

(‘u scannappoggiu): gli animatori sorreggono i pupi

poggiando i piedi su una spessa tavola di legno sospesa a

circa un metro da terra (‘a faddacca).

-

Spazio scenico: superficie d’azione dei pupi più larga che

profonda: gli animatori, camminando sul ponte di animazione,

possono seguire senza problemi il pupo per tutta la

larghezza della scena.

-

Concezione teatrale e dello spettacolo: più tragica, sentimentale e realistica.

If you remember, I told you that while I was researching the topic

of marionettes and puppets, I found, on the website of the City of

Catania (Sicily), an interesting article entitled The History of the

Sicilian Puppets written by Professor Alessandro Napoli. Having

introduced the topic and listed the elements of the tradition in the

city of Palermo, today we will examine the tradition in the city of

Catania.

[https://www.comune.catania.it/la-citta/tradizioni/pupisiciliani]

-

The pupi range from 80 centimeters to 1.30 meter in height.

-

They weigh up to 35 kilos.

-

Mechanical characteristics: they have rigid knees, without a

juncture; if the pupo is a warrior, the sword is nearly always

held in the right hand.

-

System of operation: from a bridge suspended above the

backdrop (called ‘u scannappoggiu), the puppeteers rest

their feet on a thick plank of wood suspended about 1 meter

aboveground (called ‘a faddacca).

-

The stage: the surface where the action takes place is wider

than it is deep; the puppeteers walking along the animation

bridge can follow the pupo along the entirety of the set with

no problem.

-

Theatrical and spectacle conception: more tragic, sentimental

and realistic.

|

Saturday, February 8, 2025

|

|

Se vi ricordate, la volta scorsa vi ho detto che mentre facevo delle

ricerche sul tema di marionette, burattini e pupi ho trovato, sul

sito del Comune di Catania, un articolo interessante intitolato

Storia dei Pupi Siciliani scritto dal Prof. Alessandro Napoli. Oggi

esaminiamo gli elementi della tradizione palermitana.

[https://www.comune.catania.it/la-citta/tradizioni/pupisiciliani]

LA TRADIZIONE PALERMITANA

-

Dimensioni dei pupi: da cm. 80 a un metro di altezza.

-

Peso: fino a Kg. 8 circa.

-

Caratteristiche della meccanica: ginocchia articolate; se il

pupo è un guerriero, la spada si può sguainare e riporre nel

fodero.

-

Sistema di manovra: dai lati, a braccio teso: gli animatori sono

posizionati dietro le quinte laterali del palcoscenico e

poggiano i piedi sullo stesso piano di calpestio dei pupi.

-

Spazio scenico: superficie d’azione dei pupi più profonda che

larga: la larghezza della scena è limitata dalla possibilità degli

animatori di sporgersi dalle quinte senza farsi vedere dai lati.

-

Concezione teatrale e dello spettacolo: più stilizzata ed

elementare.

~~~~~~ ~~~~~~ ~~~~~~

If you remember, last time I told you that while I was researching

the topic of marionettes and puppets, I found, on the website of

the City of Catania (Sicily), an interesting article entitled The

History of the Sicilian Puppets written by Professor Alessandro

Napoli. Today we will look at the tradition in the city of Palermo.

[https://www.comune.catania.it/la-citta/tradizioni/pupisiciliani]

THE TRADITION OF THE PUPI FROM PALERMO:

-

The pupi range from 80 centimeters to 1 meter in height.

-

They weigh up to approximately 8 kilos.

-

Mechanical characteristics: they have articulated knees, and

if the pupo is a warrior, the sword may be unsheathed and

placed back in its scabbard.

-

System of operation: from the sides and stiff-armed, the

puppeteers are placed behind the lateral scenery of the

stage, resting their feet on the same planking level of the

pupi.

-

The stage: the surface where the action takes place is

deeper than it is wide; the width of the scene is limited by the

abilities of the puppeteers to lean over the scenery flats

without being seen from the sides.

-

Theatrical and spectacle conception: more stylized and |elementary.

|

Saturday, January 25, 2025

|

|

Mentre facevo delle ricerche sul tema di marionette, burattini e pupi ho

trovato, sul sito del Comune di Catania, un articolo interessante

intitolato Storia dei Pupi Siciliani scritto dal Prof. Alessandro Napoli. Ve

lo offro in varie fasi: per prima, l’introduzione generale, poi informazioni

sulla tradizione palermitana e in fine la tradizione catanese.

[https://www.comune.catania.it/la-citta/tradizioni/pupisiciliani]

L’Opera dei Pupi è un particolare tipo di teatro delle marionette che si

affermò stabilmente nell’Italia meridionale e soprattutto in Sicilia tra la

seconda metà dell’Ottocento e la prima metà del Novecento.

I pupi siciliani si distinguono dalle altre marionette essenzialmente per

la loro peculiare meccanica di manovra e per il repertorio, costituito

quasi per intero da narrazioni cavalleresche derivate in gran parte da

romanzi e poemi del ciclo carolingio.

Le marionette del Settecento venivano animate dall’alto per mezzo di

una sottile asta metallica collegata alla testa attraverso uno snodo e

per mezzo di più fili, che consentivano i movimenti delle braccia e delle

gambe. In Sicilia, nella prima metà dell’Ottocento, un geniale artefice

di cui ignoriamo il nome escogitò gli efficaci accorgimenti tecnici che

trasformarono le marionette in pupi.

Egli fece in modo che l’asta di metallo per il movimento della testa non

fosse più collegata ad essa tramite uno snodo, ma la attraversasse

dall’interno e - cosa ben più importante - sostituì il sottile filo per

l’animazione del braccio destro con la robusta asta di metallo,

caratteristica del pupo siciliano. Questi nuovi espedienti tecnici

consentirono di imprimere alle figure animate movimenti più rapidi,

diretti e decisi, e perciò particolarmente efficaci per “imitare” sulla

scena duelli e combattimenti, che tanta parte avevano nelle storie

cavalleresche.

Esistono in Sicilia due differenti tradizioni, o “stili”, dell’Opera dei Pupi:

quella palermitana, affermatasi nella capitale e diffusa nella parte

occidentale dell’isola, e quella catanese, affermatasi nella città etnea

e diffusa, a grandi linee, nella parte orientale dell’isola ed anche in

Calabria. Le cronache raccontano che l’iniziatore dell’Opera a Catania fu

don Gaetano Crimi (1807 - 1877), il quale aprì il suo primo teatro nel

1835.

Le due tradizioni differiscono per dimensioni e peso dei pupi, per alcuni

aspetti della

meccanica e del sistema di manovra, ma soprattutto per una diversa

concezione teatrale e dello spettacolo, che ha fatto sì che nel catanese

si affermasse un repertorio cavalleresco ben più ampio di quello

palermitano e per molti aspetti diverso.

While I was researching the topic of marionettes and puppets, I found,

on the website of the City of Catania (Sicily), an interesting article

entitled The History of the Sicilian Puppets written by Professor

Alessandro Napoli. I will share it with you in various phases: firstly, a

general introduction, then information on the tradition in the city of

Palermo and finally the tradition in the city of Catania.

[https://www.comune.catania.it/la-citta/tradizioni/pupisiciliani]

The “Pupi Opera” is a specific type of marionette theatre that

formalized in Southern Italy, and mostly in Sicily between the second

half of the 1800’s and the first half of the 1900’s. Sicilian Pupi, set

themselves apart from other marionettes essentially for their specific

way of movement and for the repertoire, which is composed almost in

its entirety of stories of knights is derived mostly from tales and poems

of the Carolingian Cycle.

The marionettes from the 1700’s were animated from above via a thin

metal wand tied to the head by means of a junction or intersection and

many strings, which allowed movement of the arms and legs. In Sicily,

during the first half of the 1800’s, a brilliant artisan, whose name we do

not know, devised the useful techniques that transformed the

marionettes into Pupi.

He enabled the metal wand that controlled the movements of the head

to no longer be connected by a junction, rather traversing it from the

inside and—a far more important thing—substituting the thin thread

that animated the right arm with the strong metal wand, characteristic

of the Sicilian Pupo. These new technical devices gave the animated

figures movements that were more rapid, direct and decisive, and,

therefore, particularly efficacious to “imitate” on the stage the duels

and fights, which had comprised so many of the chivalric tales.

In Sicily there are two different traditions or “styles” of the Theatre of

the Pupi: the one from Palermo established in the capitol and spread

throughout the western part of the island, and the one from Catania,

established in the city near Mount Etna and spread, for the most part in

the eastern part of the island and even in Calabria. Stories are told

that the founder of the Theatre in Catania was Don Gaetano Crimi

(1807-1877) who opened his first theatre in 1935.

The two traditions differ in the size and weight of the pupi, according

to certain aspects of their mechanics and their system of movement,

but most of all due to a different theatrical conception of the show or

spectacle, that enabled the Catania theatre to establish a knightly

repertoire which is much broader than the one from Palermo and in

many ways, different from it.

Saturday, January 11, 2025

|

|

UN BRINDISI, CINCIN, ALLA SALUTE…

Brindare, (secondo vari vocabolari: Treccani, Garzanti Linguistica, e La

Repubblica) significa:

1. gesto che consiste nell’alzare e toccare insieme i bicchieri prima di bere. È un

invito a bere alla salute o in onore di qualcuno o come buon auspicio [seguito

dalle preposizioni a, per]. Per esempio: fare, proporre un brindisi al festeggiato,

per la vittoria, in onore di un ospite, ecc.

2. breve componimento poetico improvvisato, che si recita al momento del

brindisi.

3. in musica: Aria cantata nelle scene conviviali. (Per esempio: “Libiamo”

dall’opera La Traviata di Giuseppe Verdi.)

Quando brindiamo diciamo alla salute, cent’anni, o cincin.

La parola “brindisi” deriva dal tedesco: (ich) bring(e) dir’s: lo porto, lo offro a te

(il bicchiere, il saluto). Mentre, l’espressione cincin deriva dal cinese mandarino

di Pechino: ch’ing-ch’ing significa prego-prego.

E ora il mio brindisi:

MAKE A TOAST, DRINK TO SOMEONE’S HEALTH…

The Italian word “brindare” (according to various dictionaries: Treccani, Garzanti

Linguistica, and La Repubblica) refers to:

1. A gesture consisting of raising and touching glasses prior to drinking. It is an

invitation to drink to someone’s health, or in honor of someone, or for good

wishes [in Italian the word is followed by the prepositions “a/to”, “per/for”]. For

example: propose a toast to the birthday girl/boy, victory, the guest of honor, etc.

2. Brief poetic and spontaneous composition that is recited at the time of the

toast.

3. In music: an aria sung in convivial scenes. (For example: “Libiamo” from the

opera La Traviata by Giuseppe Verdi.)

When we toast we say: to health, 100 years, or cincin.

The word “brindisi” derives from the German: (ich) bring(e) dir’s I bring, I offer

to you (the glass, the wish). While the expression cincin comes from the

mandarin Chinese spoken in Beijing: ch’ing-ch’ing means please-please.

And now my toast: (a wish for peace and serenity, not only for New Year’s Day,

but for the entire coming year.)

HAPPY NEW YEAR TO ALL!

Saturday, December 28, 2024

|

| |

|

|

|

|